|

|

|

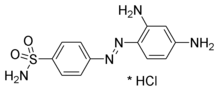

Prontosil

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 4-[(2,4-diaminophenyl)azo]benzenesulfonamide | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 103-12-8 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C12H13N5O2S - HCl |

| Mol. weight | 291.33 |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Routes | oral |

Prontosil, the first commercially available antibiotic, was developed by a research team at the Bayer Laboratories in Germany. Its discovery and development opened a new era in medicine. The molecule, first synthesized by Bayer chemists Josef Klarer and Fritz Mietzsch, was tested and found effective against some important bacterial infections in mice by Gerhard Domagk, who subsequently received the 1939 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Prontosil was the result of five years of research and testing involving thousands of chemical substances. The definitive tests were done in 1932, but results were not published until 1935, after I.G. Farben had obtained a patent. It was quickly found by a French research team at the Pasteur Institute that Prontosil, a nearly insoluble red azo dye, is broken down in the body, releasing a much simpler, colorless molecule sulfanilimide through a process called "bioactivation." Sulfanilamide, the active portion of the Prontosil molecule, was out of patent, cheap to produce, easy to link into other molecules, and soon widely available in hundreds of forms. As a result, Prontosil failed to make the profits in the marketplace hoped for by Bayer. Although quickly eclipsed by newer sulfa drugs and, in the mid-1940s and through the 1950s, penicillin and a string of newer antibiotics that proved more effective against more types of bacteria, Prontosil remained on the market until the 1960s. Prontosil's discovery ushered in the era of antibiotics and had a profound impact on pharmaceutical research, drug laws, and medical history.

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: