Saxophones of different sizes play in different registers. This

is an

alto saxophone in E flat.

Saxophones of different sizes play in different registers. This

is an

alto saxophone in E flat.The saxophone or sax is a conical-bored instrument of the woodwind family, usually made of brass and played with a single-reed mouthpiece like the clarinet. It was invented by Adolphe Sax around 1840. The saxophone is most commonly associated with popular music, big band music, and jazz, but it was originally intended as both an orchestral and military band instrument. Saxophone players are appropriately called saxophonists. Former U.S. President Bill Clinton famously played his tenor saxophone at his own inaugural ball in 1993.

Contents |

History

The saxophone was developed circa 1840 by Adolphe Sax, a Belgian-born instrument-maker, flautist, and clarinetist working in Paris. Although he had constructed saxophones in several sizes by the early 1840s, he did not receive a 15-year patent for the instrument until June 17, 1846. It was first officially revealed to the public in the presentation of the bass saxophone in C at an exhibition in Brussels in 1841. Sax also gave private showings to Parisian musicians in the early 1840s. He drew up plans for 14 different types of saxophones, but they were not all realized.

The inspiration for the instrument is unknown, but there is good evidence that fitting a clarinet mouthpiece to an ophicleide is the most likely origin. (Sax built ophicleides among other instruments in the late 1830s.) Doing so results in a an instrument with a definitely saxophone-like sound. The Hungarian/Romanian tarogato, which is quite similar to a soprano saxophone, has also been speculated to have been an inspiration. However, this cannot be so, as the modern tarogato with a single reed mouthpiece was not developed until the 1890s, long after the saxophone had been invented.

Sax's intent, which was plainly stated in his writings, was to invent an entirely new instrument which could provide bands and orchestras with a bass to the woodwind and brass sections, capable of more refined performance than the ophicleide, but with enough power to be used out-of-doors. This would explain why he chose to name the instrument the "Sound of Sax." In short, Sax intended to harness the finesse of a woodwind with the power of a brass instrument. However, Sax's amazing ability to offend rival instrument manufacturers and the resulting prejudice towards the man and his instruments led to the saxophone not being used in orchestral groups. For a long time it was relegated to military bands, despite Sax's great friendship with the influential Parisian composer Hector Berlioz.

For the duration of the patent (1846-1866) no one except the Sax factory could legally manufacture or modify the instruments, although this and Sax's numerous other patents were routinely breached by his rivals. After 1866 many modifications were introduced by a number of manufacturers.

Saxophones came to be associated, by many, with immorality. The Vatican officially condemned the instrument in the early 20th century, and various governments tried to limit their use, notably Nazi Germany and Japan in the 1930s.

The jazz saxophonist Klaus Doldinger playing the tenor sax.

The jazz saxophonist Klaus Doldinger playing the tenor sax.

Construction

The saxophone uses a single reed mouthpiece similar to that of a clarinet, but with a round or square evacuated inner chamber. The saxophone's body is effectively conical, giving it acoustic properties more similar to the oboe than to the clarinet. However, unlike the oboe, whose tube is a single cone, most saxophones have a distinctive curve at the bell. Straight soprano and sopranino saxophones are more common than curved ones, and a very few straight alto and tenor saxophones have been made, as novelties. Straight baritone and C melody saxophones have occasionally been made as custom instruments, but were never production items (reference [1], Jay Easton's custom Vito straight baritone[2] and Bennie Meroff's custom Buescher Straight Baritone [3]).There is some debate amongst players as to whether the curve affects the tone or not.

Materials

Nearly all saxophones are made from brass. After completing the instrument, manufacturers usually apply either a coating of clear or colored lacquer, or plating of silver or gold, over the bare brass. The lacquer or plating serves to protect the brass from corrosion, to enhance sound quality, and/or (in the case of colored lacquers) to give the saxophone an interesting visual appearance. That different lacquers provide different tone qualities is a hotly debated topic in the saxophone world - some say that it has no effect [4], while there is also research to show that there are differences [5]. Generally, darker lacquer is usually associated with deeper timbres, while lighter lacquers such as silver are associated with brighter, more vibrant ones.

Other materials have been tried with varying degrees of success, as with the 1950s plastic saxophones made by the Grafton company, and the rare wooden saxophones. Prior to 1960, some instruments were plated with nickel as a cheaper alternative to silver; prior to 1930, it was common for instruments to be sold with a bare brass finish (without lacquer or plating). Certain companies, such as Yanagisawa, manufacture saxophones made from bronze, which is claimed to produce a warmer sound.

The mouthpiece

Two mouthpieces for

tenor saxophone; the one on the left is for

classical music; the one on the right is for

jazz.

Two mouthpieces for

tenor saxophone; the one on the left is for

classical music; the one on the right is for

jazz.

Mouthpieces come in a wide variety of materials, including rubber, plastic, and metal. Less common materials that have been used include wood, glass, crystal, and even bone. Metal mouthpieces are believed by some to have a distinctive sound, often described as 'brighter' than the more common rubber. Some players believe that plastic mouthpieces do not produce a good tone. Other saxophonists maintain that the material has little, if any, effect on the sound, and that the physical dimensions give a mouthpiece its tone color. (Teal 17) Mouthpieces with a concave ("excavated") chamber are more true to Adolphe Sax's original design; these provide a softer or less piercing tone, and are favored by some saxophonists for classical playing.

Jazz and popular music saxophonists often play on high-baffled mouthpieces. These are configured so the baffle, or "ceiling," of the mouthpiece is closer to the reed. This produces a brighter sound which more easily "cuts through" a big band or amplified instruments. While high baffles (and the resulting tone) are commonly associated with metal mouthpieces, any mouthpiece may have a high baffle. Mouthpieces with larger tip openings provide pitch flexibility, allowing the player to "bend" notes, an effect commonly used in jazz and rock music. Classical players usually opt for a mouthpiece with a smaller tip opening and a lower baffle; this combination provides a darker sound and more stable pitch. Most classical players play on rubber mouthpieces with a round or square inner chamber.

Reeds

Frederick L. Hemke alto and tenor saxophone reeds.

Frederick L. Hemke alto and tenor saxophone reeds.

Like clarinets, saxophones use a single reed. Saxophone reeds are wider than clarinet reeds. Each size of saxophone (alto, tenor, etc.) uses a different size of reed. Reeds are commercially available in a vast array of brands, styles, and strength. Each player experiments with reeds of different strength (hardnesses) to find which strength suits his mouthpiece and playing style. Strength is usually measured using a numeric scale that ranges from 1 to 6 (though one rarely sees a reed at either end of this spectrum). Unfortunately, this scale is far from standardized between brands; thus a Rico #3 reed is decidedly softer than a Vandoren #3, for example.

Some players make their own reeds from "blanks", but as this is time-consuming and usually requires expensive equipment, most do not. Most players, however, adjust reeds by shaving or sanding. Methods for 'breaking in' reeds, caring for reeds, and adjusting reeds are controversial topics among players, and opinions about how long reeds remain playable differ greatly among players. Most players agree that reeds are somewhat inconsistent and require maintenance. Because saliva comes in contact with reeds, they should be rinsed right after playing in order to stifle germs and to prevent the saliva from deteriorating the reed's fibers. Dedicated saxophonists spend years perfecting their methods of reed selection, storage, and adjustment.

Most reeds are made from cane; however, synthetic reeds, made from various substances, are available, and are used by a small number of saxophonists. Many players consider them to have poor sound, or say they would consider them for use only in a context, such as a marching band, where tone quality is relatively unimportant. On the other hand, synthetic reeds are generally more durable than their natural counterparts, do not need to be moistened prior to playing, and can be more consistent in quality. Recent developments in synthetic reed technology has produced reeds made from synthetic polymer compounds [6], which are gaining increased acceptance among some players, especially for use when the instrument is played intermittently (during which time a natural reed might become dry).

Members of the saxophone family

Jay C. Easton with ten members of the saxophone family. From

largest to smallest: contrabass, bass, baritone, tenor, C

melody, alto, F mezzo-soprano, soprano, C soprano, sopranino.

Jay C. Easton with ten members of the saxophone family. From

largest to smallest: contrabass, bass, baritone, tenor, C

melody, alto, F mezzo-soprano, soprano, C soprano, sopranino.

The saxophone was originally patented as two families, each consisting of seven instruments. The "orchestral" family consisted of instruments in the keys of C and F, and the "military band" family in E-flat and B-flat. Each family consisted of sopranino, soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, bass and contrabass, although some of these were never made; Sax also planned--but never made--a subcontrabass (Bourdon) saxophone.

Common saxophones

In music written since 1930, only the soprano in B♭, alto in E♭, tenor in B♭ and baritone in E♭ are in common use - these form the typical saxophone sections of concert bands, military bands, and big-band jazz ensembles. The bass saxophone (in B♭) is occasionally used in band music (especially music by Percy Grainger).

The vast majority of band and big-band music calls only for E♭ alto, B♭ tenor, and E♭ baritone instruments. A typical saxophone section in a concert band might consist of four to six altos, one to three tenors, and one baritone. Occasionally a band or jazz ensemble will perform a piece that calls for soprano saxophone - in this case it is common practice for one of the players from the alto section to switch to soprano for that piece.

Most saxophone players begin learning on the alto, branching out to tenor, soprano or baritone after gaining competency. The alto saxophone is the most popular among classical composers and performers; most classical saxophonists focus primarily on the alto. In jazz, alto and tenor are predominantly used by soloists. Many jazz saxophonists also play soprano on occasion, but nearly all of them use it only as an auxiliary instrument.

The soprano has regained a degree of popularity over recent decades in jazz/pop/rock contexts, beginning with the work of jazz saxophonist John Coltrane in the 1960s. The soprano is often thought of as more difficult to play, or to keep in tune, than the more common alto, tenor and baritone saxophones. A few bass, sopranino, and contrabass saxophones are still manufactured; these are mainly for collectors or novelty use, and are rarely heard - they are mostly relegated to large saxophone ensembles.

Rare saxophones and novelty sizes

Of the orchestral family, only the tenor in C, soprano in C, and mezzo-soprano in F (similar to the modern alto) ever gained popularity. The tenor in C, generally known as the C melody saxophone, became very popular among amateurs in the 1920s and early 1930s, because its players could read music in concert pitch (such as that written for piano, voice, or violin) without the need to transpose. Although the instrument was popularized by players such as Rudy Wiedoeft and Frankie Trumbauer, it did not secure a permanent place in either jazz or classical music. The C-Melody was manufactured well into the 1930s long after its initial popularity had waned, although it became a special order item in the catalogs of some makers. The instrument is now a commonly encountered attic or garage sale relic, though since the 1980s a few contemporary saxophonists have begun to utilize the instrument once again. A similarly sized instrument, the contralto saxophone, was developed in the late 20th century by California instrument maker Jim Schmidt; this instrument has a larger bore and a new fingering system so it does not resemble the C melody instrument except for its key and register.

Also in the early 20th century, the C soprano (pitched a whole step above the B-flat soprano) was marketed to those who wished to perform oboe parts in military band, vaudeville arrangements, or church hymnals. C sopranos are easy to confuse with regular (B-flat) sopranos, since they are only approximately 2 centimeters shorter in size. None has been produced since the late 1920s. The mezzo-soprano in F (produced by the American firm Conn during the period 1928-1929) is extremely rare; most remaining examples are in the possession of serious instrument collectors. Adolphe Sax made a few F baritone prototypes, but no serious F baritones were manufactured. E-flat baritone saxes made to high pitch (A = 456) do exist and it may be easy to mistake such an instrument for an F baritone upon sight inspection alone as the high pitch model will be noticeably smaller than a low pitch one. There are no known specimens of the bass saxophone in C, the first saxophone constructed and exhibited by Sax in the early 1840s. The only known F alto made by Sax known to exist is owned by retired Canadian classical saxophonist Paul Brodie, and was found in France. Lastly, despite Ravel's scoring for a sopranino saxophone in F in Bolero, no specimen is known to exist or to have been built by Sax or any other maker.

Construction difficulties mean that only recently has a true sopranissimo saxophone been produced. Nicknamed the Soprillo, this piccolo-sized saxophone is an octave above the soprano, and its diminutive size necessitates an octave key on the mouthpiece.

Related instruments

A number of saxophone-related instruments have appeared since Sax's original work, most enjoying no significant success. These include the saxello, similar to a straight soprano but with a slightly curved neck and tipped bell; the straight alto; and the straight tenor (currently not in production; until recently, made only by a Taiwanese firm and imported to the United States by the L.A. Sax Company). Since a straight-bore tenor is approximately five feet long, the cumbersome size of such a design hinders both playing the horn (particularly when seated) and carrying it. King Saxellos, made by the H. N. White Company in the 1920s, now command prices up to US$4,000. A number of companies, including Rampone & Cazzani and L.A. Sax, are marketing straight-bore, tipped-bell soprano saxophones as saxellos (or "saxello sopranos").

Two of these variants were championed by jazz musician Rahsaan Roland Kirk, who called his straight Buescher alto a stritch and his modified saxello a manzello; this unique instrument featured a larger-than-usual bell and modified keywork. Among some saxophonists, Kirk's terms have taken a life of their own in that it is believed that these were "special" or "new" saxophones that might still be available. Though rare, the Buescher straight alto was a production item instrument while the manzello was indeed a saxello with a custom made bell.

The Tubax, developed in 1999 by the German instrument maker Benedikt Eppelsheim[7], plays the same range, and with the same fingering, as the E-flat contrabass saxophone; its bore, however, is narrower than that of a contrabass saxophone, making for a more compact instrument with a "reedier" tone (akin to the double-reed contrabass sarrusophone). It can be played with the smaller (and more commonly available) baritone saxophone mouthpiece and reeds. Eppelsheim has also produced a B-flat subcontrabass Tubax, the lowest saxophone ever made.

Another unusual variant of the saxophone was the Conn-O-Sax, a straight-bore instrument in F (one step above the E-flat alto) with a slightly curved neck and spherical bell. The instrument, which combined a saxophone bore and keys with a bell shaped similar to that of a heckelphone, was intended to imitate the timbre of the English horn and was produced only in 1929 and 1930. The instrument had a key range from low A to high G. Fewer than 100 Conn-O-Saxes are extant, and they are eagerly sought by collectors.

Bamboo "saxophones"

Although not true saxophones, inexpensive keyless folk versions of the saxophone made of bamboo were developed in the 20th century by instrument makers in Hawaii, Jamaica, Argentina, Thailand, and Indonesia. The Hawaiian instrument, called a xaphoon, is also marketed as a "bamboo sax," although its cylindrical bore more closely resembles that of a clarinet. Jamaica's best known exponent of a similar type of homemade bamboo "saxophone" was the mento musician and instrument maker Sugar Belly (William Walker). In the Minahasa region of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, there exist entire bands made up of bamboo "saxophones" and "brass" instruments of various sizes. These instruments are clever imitations of European instruments, made using local materials.

Writing for the saxophone

Music for all sizes of saxophone is written on the treble clef. The standard written range extends from a B-flat below the staff to an F or F# three ledger lines above the staff (although there are soprano models now both straight and curved that have a key for high G). Higher notes -- those in the altissimo range (ranging from high F# or above) -- can also be played using advanced techniques. Sax himself had mastered these techniques; he demonstrated the instrument as having a range of over three octaves up to a high B natural. Written articles of all sorts have referred to the altissimo as "faking" or employing "false fingerings". Both of these terms are incorrect. There is no "faking" involved, as with any other woodwind instrument, the player is simply employing the third and subsequent harmonics to extend the range of the instrument. The difference with the saxophone is that the utilization of these harmonics takes more effort on the part of the player than do other woodwinds, combined with a historical mistaken (and deeply ingrained) belief that the saxophone's range ends at high F or E-flat on older sopraninos, sopranos, baritones, and basses. Sax himself discontinued promotion of the extended range due to its perceived difficulty for the average player.

Virtually all saxophones are transposing instruments: Sopranino, alto and baritone saxophones are in the key of E-flat, and soprano, tenor and bass saxophones are in the key of B-flat. Because all instruments use the same fingerings for a given written note, it is easy for a player to switch between different saxophones. When a saxophonist plays a C on the staff on an E-flat alto, the note sounds as E-flat a sixth below the written note. A C played on a B-flat tenor, however, sounds as B-flat a ninth below. The E-flat baritone is an octave below the alto, and the B-flat soprano is an octave above the tenor. The following discussion refers entirely to the notes as written, and therefore applies equally to all members of the saxophone family.

Since the baritone and alto are pitched in E-flat, they can play concert pitch music written in bass clef by imagining it to be treble clef and adding three sharps to the key signature. On the baritone, this allows the playing of bassoon and bass parts at sounding pitch. This is a useful skill, especially if baritone sax parts are not available.

Most late-model baritone saxophones have an extra key that allows the player to play a low A (concert C), but other members of the family do not (except for some basses and a few rare altos made by The Selmer Company [8]), and composers who write this note for baritone should be aware that it may not actually be played if the saxophonist uses an older instrument.

Early on, most composers stayed away from composing for the saxophone due to their misunderstanding of the instrument. However, around the turn of the twentieth century, some people (many from the United States) began to commission compositions for the instrument. One prominent commissioner was Elise Hall, a wealthy New England socialite who took up playing the saxophone to aid in her battles with asthma (at the behest of her husband, a doctor). Though she did commission many pieces, the works didn't originally feature the saxophone very well (probably because she decided to demonstrate herself the saxophone's ability-- her skills were less than admirable by most accounts). Subsequent versions, however, have been arranged to better feature the saxophone, such as the "Rhapsodie" by Claude Debussy.

The saxophone in ensembles

Besides functioning as a solo instrument, the saxophone is also an effective ensemble instrument, particularly when several members of the saxophone family are played in combination. Although only occasionally called for in orchestral music, saxophone sections (usually encompassing the alto, tenor, and baritone instruments, but sometimes also the soprano and/or bass) are an important part of the jazz big band, as well as military, concert, and marching bands.

Ensembles made up exclusively of saxophones are also popular, with the most common being the saxophone quartet (comprising the soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone instruments, or, more rarely, two altos, tenor, and baritone). There is a repertoire of classical compositions and arrangements for this instrumentation dating back to the nineteenth century, particularly by French composers who knew Adolphe Sax. The Raschèr [9], Amherst [10], Aurelia [11] and Rova Saxophone Quartets are among the most well known groups, and the World Saxophone Quartet is the preeminent jazz saxophone quartet. Historically, the Marcel Mule and Daniel Deffayet Quartets were highly regarded, beginning in 1928 and 1953, respectively. The Mule quartet is often considered to be the prototype for all future quartets due the level of virtuosity demonstrated by its members and its central role in the development of the quartet repertoire. Organized quartets did indeed exist prior to Mule's ensemble, the prime example being the quartet headed by Eduard Lefebre (1834-1911), former soloist with the Sousa band, in the United States circa 1904-1911. Other ensembles most likely existed at this time as part of the saxophone sections of the many touring "business" bands that existed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Larger all-saxophone ensembles exist as well. The most prominent professional saxophone ensembles include the Raschèr Saxophone Orchestra [12], London Saxophonic [13], Nuclear Whales Saxophone Orchestra [14], and Urban Sax. Very large groups, featuring over 100 saxophones, are sometimes organized as a novelty at saxophone conventions [15].

Technique

Many believe it is relatively easy to become a competent saxophonist, especially when transferring from other woodwind instruments, but a considerable amount of practice is usually required to develop a pleasing tone color and fluent technique.

Playing technique for the saxophone is subjective based upon the intended style (classical, jazz, rock, funk, etc.) and the player's idealized sound. The design of the saxophone allows for a big variety of different sounds, and the "ideal" saxophone sound and keys to its production are subjects of debate. However, there is a basic underlying structure to most techniques.

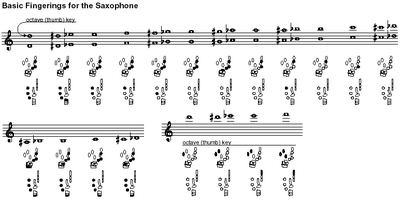

The fingerings for a saxophone do not change from one instrument

to another. Here, notes on a treble staff correspond to

fingerings below.

The fingerings for a saxophone do not change from one instrument

to another. Here, notes on a treble staff correspond to

fingerings below.

Fingerings typically appear with the left and right hand

side-by-side.

Fingerings typically appear with the left and right hand

side-by-side.

The embouchure

In the typical embouchure, the mouthpiece is generally not taken more than half-way into the player's mouth. The lower lip is supported by the lower teeth, and makes contact with the reed. The playing-position is stabilised with firm,light pressure from the upper teeth resting on the mouthpiece (sometimes padded with a thin strip of rubber known as a "bite-pad" or "mouthpiece-patch"). The upper lip closes to create an air-tight seal. The "double embouchure" in which the upper lip is curled over the upper teeth is not commonly used in modern times, however each player may eventually develop his/her own variation of the basic embouchure style in order to accommodate their own physical structure.

Two things are imperative to a full and quick-speaking sound: appropriate air pressure which is aided by diaphragm support and correct lip/reed contact allowing the reed to vibrate optimally. The player's diaphragm acts as a bellows, supplying a constant stream of air through the instrument. The throat should feel open, as when yawning. This openness should remain throughout the register of the saxophone, especially the low register (D down to B-flat).

Vibrato

Saxophone vibrato is much like a vocal or string vibrato, except the vibrations are made using the jaw instead of the diaphragm or fingers. The jaw motions required for vibrato can be simulated by saying the syllables "wah-wah-wah". While most will say vibrato is not vital to saxophone performance (as its importance is inferior to proper tone quality), many argue it as being integral to the distinct saxophone color. Classical vibrato can vary between players (soft and subtle, or wide and abrasive). Jazz vibrato is typically standard amongst its users; fast and wide in fast tempos, delayed and soft in slower tempos. Players just starting out with vibrato will usually start out slow with exaggerated jaw movements. As they progress, the vibrato becomes quicker until the desired speed is reached.

Tone effects

A number of effects can be used to create different or interesting sounds.

- Growling is a technique used whereby the saxophonist sings, hums, or even "growls", using the back of the throat while playing. This causes a modulation of the sound, and results in a gruffness or coarseness of the sound. It is rarely found in classical or marching band music but often found in jazz, blues, rock 'n' roll and other popular genres. Some notable musicians utilizing this technique are Boots Randolph, Gato Barbieri, Ben Webster, Clarence Clemons and King Curtis.

- A glissando or sliding technique can also be used. Here the saxophonist bends the note using the embouchure and at the same time slides up or down to another fingered note. This technique is sometimes heard in big band music (for example, Benny Goodman's "Sing Sing Sing") and even in an orchestral score (George Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue").

- Multiphonics is the technique of playing more than one note at once. A special fingering combination causes the instrument to vibrate at two different pitches alternately, creating a warbling sound.

- The use of overtones involves fingering one note but altering the air stream to produce another note which is an overtone of the fingered note. For example, if low B-flat is fingered, a B-flat one octave above may be sounded by manipulating the air stream. Other overtones that can be obtained with this fingering include F, B-flat, and D. The same air stream techniques used to produce overtones are also used to produce notes above high F (the "altissimo register").

- This technique of manipulating the air stream is now commonly known as "voicing." Voicing technique, which is often compared to whistling, basically involves varying the position of the tongue, causing the same amount of air to pass through either a more or less confined oral cavity. This, in turn, causes the air stream to either speed up or slow down, respectively. As well as allowing the saxophonist to play overtones/altissimo with ease, proper voicing also helps the saxophonist develop a clear, even and focused sound throughout the range of the instrument. For a thorough discussion of proper voicing technique see "Voicing" by Donald Sinta and Denise Dabney.

Electronic effects

The use of electronic effects with the saxophone began with innovations such as the Varitone system, which Selmer introduced in 1965. The Varitone included a small microphone mounted on the saxophone neck, a set of controls attached to the saxophone's body, and an amplifier and loudspeaker mounted inside a cabinet. The Varitone's effects included echo, tremolo, tone control, and an octave divider. Two notable Varitone players were Eddie Harris and Sonny Stitt. Similar products included the Hammond Condor.

In addition to playing the Varitone, Eddie Harris experimented with looping techniques on his 1968 album Silver Cycles.

David Sanborn and Traffic member Chris Wood employed effects such as wah-wah and delay on various recordings during the 1970s.

In more recent years, the term "saxophonics" has been used to describe the use of these techniques by saxophonists such as Skerik, who has used a wide variety of effects that are often associated with the electric guitar.

Popular Brands

Popular manufacturers of Saxophnes include King, Selmer, Yamaha, Conn, and Jupiter.

References

- Teal, Larry (1963): The Art of Saxophone Playing. Miami:Summy-Birchard. ISBN 0-87487-057-7

Robert Howe, "Invention and Development of the Saxophone 1840-55", Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society, 2003

External links

- Adolphe Sax, by Léon Kochnitzky

- Pete Thomas Sax Site Excellent resources.

- World Saxophone Congress 2006, Ljubljana - Slovenia

- The International Saxophone Home Page

- Sax on the Web Lessons, tips, articles, and discussion forum.

- Introduction to Saxophone Acoustics from Music Acoustics at the University of New South Wales.

- Saxophone fingering chart

- SaxTalk Saxophone news and articles.

- The Vintage Saxophone Gallery Vintage saxophone pictures and research.

- alt.music.saxophone/rec.music.makers.saxophone One of the first Saxophone FAQs on the web

- Time line of saxophone history

- Forum for the Saxophonist

- Sax Music Plus (helpful advice and articles on the art of saxophone playing)

- SaxTips Podcast (the first and only Saxophone Workshop on the Web as a Podcast)

- A world of bamboo (Bamboo saxophones webpage from Argentina)

- Keith Gemmell's Saxophone site Advice and help on playing the sax

Categories: Woodwind instruments | Aerophones | Musical instruments

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: