The organ of

Bristol Cathedral, Bristol, England. Many of the pipes date back to 1685, although

the organ has been rebuilt many times since then.

The organ of

Bristol Cathedral, Bristol, England. Many of the pipes date back to 1685, although

the organ has been rebuilt many times since then.

Organ in Katharinenkirche, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Organ in Katharinenkirche, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Pipe organ at the Aletheia University in Matou/Taiwan

Pipe organ at the Aletheia University in Matou/Taiwan

A pipe organ is a keyboard instrument that produces its sound by admitting air under pressure through pipes. Pipe organs range in size from portable instruments having only a few dozen pipes to very large symphonic organs with tens of thousands of pipes. All but the smallest have more than one keyboard (manual), with the most common configuration being two manuals and a pedalboard. Three, four or five manuals and pedals is not uncommon for larger instruments.

Pipe organs are most commonly found in churches, and in some Reform synagogues. They are also found in town halls, and in arts centres intended for the performance of classical music. In the era of silent films, large theater organs were installed in many cinemas.

Contents |

History

As one of the oldest instruments still in use, the organ has a long and rich history.

The first organs

The word organ originates from the Latin word "organum", the earliest predecessor of the instrument used in ancient Roman circus games and similar to a modern portative.

Among the music-making angels accompanying

Domenico di Bartolo's Madonna of Humility, Siena

1433, the angel on the right plays a

portatif with a set of hand-pumped bellows.

Among the music-making angels accompanying

Domenico di Bartolo's Madonna of Humility, Siena

1433, the angel on the right plays a

portatif with a set of hand-pumped bellows.

The organ dates back to classical antiquity. The earliest organs were hydraulic. The inventor most often credited is Ctesibius of Alexandria, an engineer of the 3rd century BC, who created an instrument called the hydraulis. The hydraulis was common in the Roman Empire, where its immensely loud tone was heard during games and circuses in amphitheatres and processions. Characteristics of this instrument have been inferred from mosaics, paintings, literary references and partial remains, but knowledge of details of its construction remain sparse, and almost nothing is known of the actual music it played.

Carlo Dolci painted Saint Cecilia at a portatif organ, 1671.

Carlo Dolci painted Saint Cecilia at a portatif organ, 1671.

Organs were also known to exist in the Byzantine Empire as well as in Islamic Spain, though there is no evidence that the European organ came by way of Spain. In medieval times, the portable instruments (the portatif or portative organ and the positive organ) were invented. Because of their portability, they were used for the accompaniment of both sacred and secular music in a variety of settings.

Blockwerk

As the instruments became larger, they were installed permanently in a fashion similar to the church organs of today. At this time, organs did not have sophisticated stop controls: the organist would usually have the choice of playing on a single 8' Principal stop or what was called the Blockwerk. The Blockwerk consisted of the entire tonal resources of the organ, which in some cases meant a very large number of ranks ranging from 16' pitch all the way through 1' pitch and higher.

Eventually, separate controls were built to allow the organist to control whether or not each rank in the Blockwerk would sound, effectively dividing the Blockwerk into separate stops. Some of the higher-pitched ranks were still grouped together under a single stop control; these stops were the forerunner of mixtures that would be found in later organs.

The Renaissance and Baroque eras

During the Renaissance and Baroque eras the organ became an instrument capable of creating numerous tonal colors, both unique and imitative. In northern Europe, the organ developed into a large instrument with several divisions, including an independent pedal. These divisions were readily discernible by the case design. This style was labeled the Werkprinzip by 20th-century organ scholars. In France, the French classical organ came into fashion, a style of building articulated most completely by Dom Bedos de Celles in his magnum opus, L'art de facteur d'orgues.

Romantic era

In the Romantic era the organ transitioned from a polyphonic to a symphonic instrument, capable of creating a massive layered crescendo from the softest stops alone to the full organ. Through the developments of the French organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, the romantic organ inspired generations of composers, beginning with César Franck and continuing through the 20th century. In the Romantic era organs began to be built in concert halls, and the organ began to be called for in large symphonic works by such composers as Camille Saint-Saëns and Gustav Mahler.

20th century

A major revolution in pipe organ design took place in the late-19th century when the development of electric and electro-pneumatic key actions made it technically feasible to locate the console independently of the pipes. Up until the historical organ revival in the mid-20th century, electric key action reigned supreme. When organ builders began building historically-inspired instruments, they returned to mechanical key action. Due to the benefits of modern technology, modern mechanical actions are much lighter and require less effort to play than do historical mechanical actions. During the 20th century, electrically-controlled stop actions allowed for the development of sophisticated combination actions.

Pipeless organs

In the mid-20th century, churches and other institutions began increasingly substituting electronic pipeless organs such as the Hammond organ(see organ (music)) for pipe organs, because pipe organs are more expensive and harder to maintain. In the later 20th century, digital pipeless instruments were developed that emulate the sound of a real organ. Both Hammond organs and modern digital organs have to be amplified using an electronic instrument amplifier and speakers that are designed to reproduce the full range of tones that an organ produces. Modern digital sampling organs are by far the most realistic imitation of the true pipe organ sound (though still merely an imitation). Major builders of such instruments include the firms of Allen, Rodgers, Johannus and Phoenix. It is increasingly common for even builders of real pipe organs today to use digital stops for the very lowest pedal ranks.

Despite the lower cost of electric and digital pipeless organs (as compared with the cost of a pipe organ), interest in pipe organs and mechanical actions for pipe organs has continued. Historic organs are still being rebuilt and refurbished, and new instruments with both mechanical and electric actions are being built.

Construction

The main elements of an organ are the pipes, the console (or keydesk), the wind system, and the stop mechanism.

Pipes

The main portion of the pipe organ at St. Raphael's

Cathedral in Dubuque, Iowa. This organ features an open case design

where the pipes are left exposed. The swell shutters can be

seen open in the rear.

The main portion of the pipe organ at St. Raphael's

Cathedral in Dubuque, Iowa. This organ features an open case design

where the pipes are left exposed. The swell shutters can be

seen open in the rear.

Organ pipes are arranged in ranks. A rank is a complete set of pipes of similar timbre tuned to a chromatic scale. The great majority of ranks are mounted vertically, but some ranks may be mounted horizontally, as is the case with trompettes en chamade. At the base of the pipes is a windchest which supplies air (known in the organ world as "wind") to the pipes. The manner in which the wind is admitted to the pipes varies depending on the type of action, but in any case several ranks of pipes may be supplied by a single windchest. A few of the larger pipes may be "off chest" in order to better fit them into the available space or in order to feature them in the façade.

Pipes may be classified in several ways, each of which results in a different timbre:

- by the material they are made of (wood or metal)

- by the mechanism of sound production (flue pipes vs. reed pipes, also called labial and lingual)

- by the shape of the pipe (cylindrical, conical, or irregular)

- by the construction of the ends (open or closed).

Because a pipe produces only one pitch at a time, ideally there is at least one pipe for each controlling key or pedal. (Occasionally some pipes, especially in the bass, to save space or material, are rigged to provide multiple pitches like big recorders: this method was employed especially by a few builders in the early 20th century.) Thus, a keyboard with 61 notes would have 61 pipes per rank.

The choir division of the pipe organ at St. Raphael's

Cathedral in Dubuque, Iowa. Unlike the rest of the organ—which is

located in the galley at the rear of the church—this

division is located in the choir area near the front of the

church.

The choir division of the pipe organ at St. Raphael's

Cathedral in Dubuque, Iowa. Unlike the rest of the organ—which is

located in the galley at the rear of the church—this

division is located in the choir area near the front of the

church.

Pitch

The pitch produced by a pipe is a function of its length. A stop may be tuned to sound (or speak at) the pitch normally associated with the key that is pressed (the written pitch or unison pitch), or it may speak at a fixed interval above or below this pitch. These intervals are denoted by numbers on the stop knob. A stop tuned to unison pitch is known as an 8' stop (pronounced "eight foot"). This refers to the approximate speaking length of an open flue pipe of that stop sounding CC (the C two octaves below middle C). A 4' stop (so called because its CC pipe is approximately four feet long) speaks an octave above unison pitch. Thus, the pitches which sound the octaves above and below unison pitch correspond to the powers of two: 1' is three octaves above unison pitch, 2' two octaves above, 4' one octave above, 8' unison pitch, 16' one octave below, 32' two octaves below, and 64' (extraordinarily rare) three octaves below. When considering the labeled lengths of ranks of pipes, the length of a foot is 328 mm when the speed of sound is 343 m/s.

Ranks pitched at some interval that is not a power of two (such as 2 2/3' or 1 3/5') are also common. These mutations reinforce certain partials of the overtone series of a fundamental. A stop at 2 2/3' pitch (called a "Nasard" or a "Quint") sounds at an interval of a twelfth above unison pitch, and a stop at 1 3/5' pitch (called a "Tierce") sounds at an interval of a seventeenth above unison pitch. (In some historical organs a stop at 2 2/3' pitch is labeled as 3'; this is purely a representation of historical convention and does not indicate that the stop is any different from one labeled 2 2/3'.) Normally, mutation stops are not played by themselves, they are combined with fundamental stops. They are most often used to add unique color to solo combinations.

Certain stops called mixtures contain multiple ranks of pipes. The number of ranks in a mixture is denoted by a Roman numeral in the stop name: a stop labeled "Mixture V" on a 61-note keyboard would contain 5 × 61 = 305 pipes. The multiple ranks in a mixture (usually pitched at intervals of octaves and fifths, though mixtures containing thirds also exist) reinforce certain partials of a fundamental, like mutations; however, mixtures are generally used to color the plenum as opposed to solo combinations.

Flue pipes

Flue pipes produce sound the same way as a recorder: they are actuated by a whistle or fipple. The majority of organ pipes are flue pipes. They are used in single-rank foundation and mutation stops as well as mixtures.

Most, but not all, flue pipes belong to one of three tonal families:

- Flutes have the purest waveforms, but have less-defined pitch than diapasons.

- Diapasons or principals have the most well-defined pitches and have a tone midway between flutes and strings.

- Strings have the richest harmonics and the narrowest pipe scales.

Ranks of all three tonal families may have either open ends or closed ("stopped") ends. The cross-section of a metal pipes is normally circular, while the cross-section of a wooden pipe is most often square or rectangular.

Flue pipes can be made of wood or metal. Metal flues are made of varying mixtures of lead and tin, according to the sound sought for that particular pipe (lead darkens the tone, tin brightens it). The exception is the very lowest pipes in a rank, which are sometimes made of rolled zinc. Wood flues will always have the foot, cap, block and mouthpiece made of hardwood, whereas the walls of the pipe may be made of hardwood or (commonly in very large pipes) of conifer.

Reed pipes

Reed pipes are actuated by a beating reed. They are used almost exclusively as single-rank foundation stops. Because they contain moving parts, their construction is more complicated. Reed stops feature several different shapes of resonators and a great variety in tone color. Many reed stops imitate other historical musical instruments, such as the trumpet, the bassoon, the krummhorn, and the regal.

The set of chimes in the organ at

St. Raphael's Cathedral, Dubuque, Iowa.

The set of chimes in the organ at

St. Raphael's Cathedral, Dubuque, Iowa.

The reed in a reed pipe is made of brass. The pipe's sound is created entirely inside the pipe foot (or "boot"), but is amplified and given its respective color by the resonator, which projects upward from the boot. Resonators can be shorter than the corresponding pipe of a flue rank of the same pitch (called "fractional length"), of unison length, or twice as long (called "double length"), depending on the tone desired. They can be cylindrical and high in lead content (as in the Krummhorn) or conical and high in tin content (as in the Trompette). In addition, they can be narrowly flared, broadly flared, capped, semi-capped or open. All these variations have an effect on the tone produced.

Accessories

In addition to pipes, some organs will have any of several accessories. The zimbelstern is quite common, especially on German Baroque-inspired instruments. The chimes and the celesta are normally found on American instruments, while the harp, the drum, and other percussion stops are rather rare. French romantic instruments sometimes feature the éffet d'orage (the "thunder pedal") and the avalanche, used in the performance of storm compositions and improvisations.

Stop nomenclature

Many stops have more than one name. The choice of the name reflects not only the timbre and construction of the stop, but also the style of the organ in which the stop resides. For example, the stop names on a German Baroque organ will generally be derived from the German nomenclature, while the names of similar stops on an English romantic organ will be derived from the English tradition.

Stops of the Baroque Gabler organ in

Weingarten, Germany.

Stops of the Baroque Gabler organ in

Weingarten, Germany.

A traditional stop label includes three parts:

- the name of the stop (Rohrflöte, Cornet, Trompette, etc.)

- the pitch (8', 4', etc.)

- the number of ranks controlled by the stop (III, VI–VIII, etc.)

Thus, a stop labeled 8' Cornet V is a five-rank Cornet whose lowest pitched rank sounds at unison pitch. If—as in most cases—the stop controls only one rank, the "I" is normally omitted (i.e., 8' Principal, not 8' Principal I). Conventionally, a resultant bass (or resultant) stop, which plays two or more ranks in a harmonic series in order to create the illusion of a lower pitch, is labeled only with the resultant tone. For example, the relatively common combination of a 16' rank and a 10 2/3' rank, producing the impression of 32' tone, would be labelled Resultant 32'. Stop nomenclature was more strictly observed in classic organ building than it is today, in some ways. Classically, a "twelfth" and a "nasard" were essentially similar stops, but the term "twelfth" was used if the pipes were made as diapasons, and the term "nasard" was used if the pipes were made as flutes. Today, the term "twelfth" is little used, and "nasard" pipes may be either diapasons or flutes in design.

Unification and extension

When a rank of pipes is available as part of more than one stop, the rank is said to be unified, or borrowed. Ranks can be borrowed within a single division or between manuals. For example, an 8' Diapason rank may also be made available as a 4' Octave. When both of these stops are selected and a key (for example, middle C) is pressed, two pipes of the same rank will sound: the middle C pipe and the pipe one octave higher.

Furthermore, if both the middle C key and the C an octave higher are pressed simultaneously, only three pipes will sound. This is because one pipe has been selected twice: once as the 4' Octave of middle C and once as the 8' Diapason of the key an octave higher. This is known as a "borrowing collision", and is one reason that borrowing from a rank is generally regarded as inferior to including a separate rank. Moreover, a dedicated 4' stop would be voiced and scaled slightly differently than the 8' stop; there is no opportunity to do this with a borrowed rank.

Due to the necessities of the technique, unification is difficult to accomplish without electric stop action. It is generally used when funds are scarce, as unifying one rank with another is much cheaper than building two separate ranks. Some organ builders, such as Schoenstien, have been successful (i.e., they have not compromised the unity or the quality of the instrument) in making extensive use of unification in order to allow for unique registrational effects.

When a rank is borrowed, the organist may run out of pipes at one end of the keyboard or the other. In the above example, there are no pipes in the original rank to sound the top octave of the keyboard at 4'. The neatest and most common solution to this is to provide an extra octave of pipes used only for the borrowed 4' stop. The full rank of pipes is now an octave longer than the keyboard, and is called an extended rank or an extension rank. An organ that relies heavily on extension is called an extension organ.

Console

The organ is played from an area called the console (if it is separate from the rest of the case) or keydesk (if it is integrated into the case), which holds the manuals, pedals, and stop controls. Some very large organs, such as the Van Den Heuvel organ at the Church of St. Eustache in France, have more than one console, enabling the organ to be played from several locations depending on the nature of the performance.

The four-manual organ console at St. Mary Redcliffe church,

Bristol, England. The organ was built by Harrison and Harrison in

1912 and restored in 1990.

The four-manual organ console at St. Mary Redcliffe church,

Bristol, England. The organ was built by Harrison and Harrison in

1912 and restored in 1990.

Controls at the console called stops select which ranks are used. These controls are generally either stop knobs, which move in and out of the console, or stop tabs, which rock back and forth. Other stop controls include sliding rods and light-up digital buttons, though these styles are much less common than knobs and tabs.

Different combinations of stops change the timbre of the instrument considerably. The selection of stops is called the registration. On modern organs, the registration can be changed instantaneously with the aid of a combination action, usually featuring pistons. Pistons are buttons that can be pressed by the organist to change registrations; they are generally found between the manuals or above the pedalboard (in the latter case they are called toe studs). Most large organs have both preset and programmable pistons, with some of the couplers repeated for convenience as pistons and toe studs. Programmable pistons allow comprehensive control over changes in registration.

In organs that use electronic action, the console is sometimes moveable. This allows for greater flexibility in placement of the console for various activities. For example, the console at St. Raphael's Cathedral, in Dubuque, Iowa is moveable. The electric-action console is located near the front of the church, while most of the organ pipes are located in the former choir loft, with a few at the front of church along the southern wall. Normally, the console is positioned so that it is next to the wall, with the organist seated so his back is to the wall. For recitals, the console is often moved into better view of the audience.

Keyboards

The organ is played at least one keyboard, with configurations featuring from two to five keyboards being the most common. A keyboard to be played by the hands is called a manual (because it is played with the hands); an organ with four keyboards is said to have four manuals. Most organs also have a pedalboard, a large keyboard to be played by the feet.

The collection of ranks controlled by a particular manual is called a division. The names of the divisions of the organ vary geographically and stylistically. Common names for divisions are:

- Great, Swell, Choir, Solo, Orchestral, Echo, Antiphonal (America)

- Hauptwerk, Rückpositiv, Oberwerk, Brustwerk, Schwellwerk (Germany)

- Grand Choeur, Grand Orgue, Récit, Positif, Bombarde (France)

In English, the main manual (the bottom manual on two-manual instruments or the middle manual on three-manual instruments) is traditionally called the Great, and the upper manual is called the Swell. If there is a third manual, it is called the Choir and placed below the Great. If it is included, the Solo manual is usually placed above the Swell. Some larger organs contain an Echo or Antiphonal division, usually controlled by a manual placed above the Solo. German and English organs generally use the same configuration of manuals as American organs. On French instruments, the main manual (the Grand Orgue) is at the bottom, with the Positif and the Récit above it. If there are more manuals, the Bombarde is usually above the Récit and the Grand Choeur is below the Grand Orgue.

In some cases, an organ contains more divisions than it does manuals. In these cases, the extra divisions are called floating divisions and are played by coupling them to another manual. Usually this is the case with Echo/Antiphonal and Orchestral divisions, and sometimes it is seen with Solo and Bombarde divisions.

Couplers

A device called a coupler allows the pipes of one division to be played by a manual. For example, a coupler labeled "Swell to Great" allows the stops of the Swell division to be played by the Great manual. It is unnecessary to couple the pipes of a division to the manual of the same name (for example, coupling the Great division to the Great manual), because those stops play by default on that manual (though this is done with super- and sub-couplers, see below). By using the couplers, the entire resources of an organ can be played simultaneously from one manual. On a mechanical-action organ, a coupler may connect one division's manual directly to the other, actually moving the keys of the first manual when the second is played.

Some organs feature super-couplers and sub-couplers, which shift the connection of the coupler respectively up or down by an octave. Super-couplers are usually labeled with the suffix "4'", as in "Swell to Great 4'", and sub-couplers with the suffix "16'", as in "Swell to Great 16'". The inclusion of these couplers allows for greater registrational flexibility and color. Some literature (particularly romantic literature from France) calls explicitly for octaves aigues (super-couplers) to add brightness, or octaves graves (sub-couplers) to add gravity. Some organs feature extended ranks to accommodate the top and bottom octaves when the super- and sub-couplers are engaged (see the discussion under "Unification and extension").

Some organs also have unison off couplers, which act to "turn off" the stops of a division on its own keyboard. For example, a coupler labeled "Great unison off" would keep the stops of the Great division from sounding, even if they were pulled. Unison off couplers can be used in combination with super- and sub-couplers to create complex registrations that would otherwise be possible. In addition, the unison off couplers can be used with the standard couplers to change the order of the manuals at the console: engaging the Great to Choir and Choir to Great couplers along with the Great unison off and Choir unison off couplers would have the effect of moving the Great to the bottom manual and the Choir to the middle manual.

Wind system

For more information, see the article at Organ wind systems.

A view from behind the case of the organ at St. Raphael's

Cathedral in Dubuque shows some of the pipes, the interior

of the case, and part of the wind system.

A view from behind the case of the organ at St. Raphael's

Cathedral in Dubuque shows some of the pipes, the interior

of the case, and part of the wind system.

In order for an organ to sound, it is necessary for air to be directed through the pipes. The air, referred to as wind in the organ trade, comes from one of two sources:

- When signalled by the organist (often using a bell called a calcant ), a person pumps the bellows of the organ by any of several mechanisms, supplying them with air. Before the advent of electricity, this is how all organs were provided with wind. Playing the organ in these days required at least one person to work the bellows, if not several, who had to be compensated for time and labor, making it an expensive instrument to play. Thus, practicing was usually done not on the organ, but on smaller instruments such as the clavichord or harpsichord. A few organs that can be pumped by hand still exist.

- An electric blower fills the bellows with air. Once electricity made the electric blower a reality, every new organ made use of it and virtually every old organ was outfitted with one. Suddenly, it became possible for organists to practice regularly on the organ.

Once the wind is produced through one of these two means, it is stored in one or more bellows of varying designs. The bellows are weighted to produce a constant wind pressure, which differs with the design of the organ and the division the wind supplies. An Italian organ from the Renaissance may feature a wind pressure of only 1 1/2 inches, while an orchestral organ from the early 20th century may have wind pressures as high as 25 inches in some divisions.

The wind flows from the bellows through one or more large pipes known as wind trunks to the separate divisions of the organ. There, the wind is fed into the windchest, which is directly under the pipes. Then, through the key action, the wind flows into the pipes, and the pipes speak.

Stop mechanism

The organ's separate ranks are called into play by the organist through the stop mechanism. There are many different varieties of stop mechanisms, some proprietary, but the principal distinction is between mechanical and electric mechanisms. Mechanical stop mechanisms connect the stop controls directly to the windchests through a series of wooden or metal rods. When the organist moves the stop control, the rods move. This actuates the mechanism at the windchest that allows or denies wind to the stop. Electric stop mechanisms control the mechanism at the windchest through electronics, which are activated when the organist moves a stop control at the console.

The choice of stop mechanism depends on the design of the organ and the console. If the console is located farther away from the rest of the organ, a mechanical stop action is harder to implement than when the console and the organ are in closer proximity. Furthermore, a sophisticated combination action requires an electric stop action. A rudimentary system of combination pedals can be employed with a mechanical stop action, but it offers less registrational flexibility than an electric stop mechanism with a combination action.

Enclosure

The above elements of most organs are housed in a free-standing organ case or a dedicated room called an organ chamber. In either situation, the pipes are separated from the listeners by a grill that often contains decorative pipes known as a façade. Some organs do not have any discernable pipe façade (this is, in fact, a type of case design in itself), or they may have a screen behind which all of the organ's pipes are hidden.

In some organs with façade pipes, especially those which are based on historical styles from the time before the 20th century, the façade pipes are genuine, speaking pipes. They usually form part of an open flue rank from the Pedal or Great division. In other organs, the façade pipes are purely decorative and non-speaking.

Even with non-speaking pipes, the façade is considered an important part of an organ, much as the scroll of a violin is considered a part of that instrument. The façade also serves an acoustic function, changing the tone of the organ as the sound waves travel through it, as well as a means of masking swell boxes located behind it.

Organ music

There is a large repertoire of religious music for the pipe organ, dating from the Renaissance to the present day; in the 19th century and later compositions that were effectively secular also became common, many in symphonic style. Some of the leading composers for the pipe organ, such as Cesar Franck and Charles-Marie Widor, are relatively little-known outside the organ world; probably the two composers who both enjoy a stellar reputation in the broader musical world and composed extensively for the pipe organ are the Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach and the 20th-century composer Olivier Messiaen.

Although most countries whose music falls into the Western tradition have contributed works to the pipe organ's repertoire, France and North Germany are particularly notable for having produced many composers for the instrument. There is also extensive repertoire from the Low Countries, England and the United States.

The development of the repertoire has gone hand in hand with the development of the instrument, leading to distinctive national styles of composition; in the opposite direction, the dominance of certain countries in providing the repertoire has influenced the emergence of an international mainstream of organ design. Thus the repertoire of Spain, Portugal and Italy is rarely heard outside those countries, because the tonal styles of their organs are quite distinct from the German-French-British-American mainstream. Likewise, there is little Russian or Greek organ music because those nations' Orthodox churches do not use the organ in worship.

Church-style pipe organs are very rarely used in popular music. In some cases, groups have sought out the sound of the pipe organ, such as Tangerine Dream, which combined the distinctive sounds of electronic synthesizers and pipe organs when it recorded both music albums and videos in several cathedrals in Europe. Rick Wakeman of British progressive rock group Yes also used pipe organ to excellent effect in a number of the groups albums (including "Close To The Edge" and "Going For The One"). Wakeman has also used pipe organ in his solo pieces such as "Jane Seymour" from "The Six Wives Of Henry VIII" and "Judas Iscariot" from "Criminal Record". Even more recently, he has recorded an entire album of organ pieces - "Rick Wakeman at Lincoln Cathedral"

On the other hand, electronic organs and electromechanical organs such as the Hammond organ have an established role in a number of non-"Classical" genres, such as blues, jazz, gospel, and 1960s and 1970s rock music. Electronic and electromechanical organs were originally designed as lower-cost substitutes for pipe organs. Despite this intended role as a sacred music instrument, electronic and electromechanical organs' distinctive tone-often modified with electronic effects such as vibrato, rotating Leslie speakers, and overdrive-became an important part of the sound of popular music. Billy Preston and Iron Butterfly's Doug Ingle have featured organ on popular recordings such as "Let it Be" and "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida", respectively. Well-known rock bands using the Hammond organ include Pink Floyd and Deep Purple.

Some notable pipe organs

The world's oldest playable pipe organ is located in the Basilica of Valère in Sion, Switzerland. Built around 1390, it still contains many of its original pipes.

The largest pipe organ ever built, containing more than 32,000 pipes, is the Main Auditorium Organ in Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey, built by the Midmer-Losh Organ Company between 1929 and 1932. Today, the instrument is only partially assembled but unplayable, and indeed, was only fully assembled and operative for a short portion of its life - the space in the hall that some of the organ chambers took up being needed for other purposes.

The largest functioning pipe organ, with over 28,000 pipes, is the Grand Court Organ at Wanamaker's department store (now Lord and Taylor) in Philadelphia. It is also the second largest organ yet built.

The world's largest all pipe church organ, with about 21,800 pipes and some 355 ranks, is at the Cadet Chapel, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York. (Details: 355+ ranks, 874 stops, 293 voices, 24 divisions, 23,500 pipes. [1]) The world's next largest church pipe organ, with 20,000 pipes and 345 ranks, is at First Congregational Church, Los Angeles. Details: [2] Stoplist: [3]

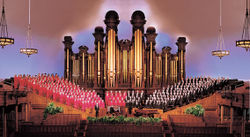

The

Mormon Tabernacle Choir pictured in front of the Tabernacle

Organ, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The

Mormon Tabernacle Choir pictured in front of the Tabernacle

Organ, Salt Lake City, Utah.

One of the most recognizeable pipe organs, also one of the largest, is in the Tabernacle on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, UT. It is also of note that the largest pipes in the façade, which typically are made of metal, are made of a series of wood strips glued together in barrel-stave fashion. The lumber for these pipes as well as other wood portions of the organ and the structure of the building itself were hauled to the site by oxen from from the Parowan and Pine Valley mountains nearly 300 miles away.

References

- Sumner, William Leslie. "The Organ: Its Evolution, Principles of Construction and Use." ISBN 0781205727

- Williams, Peter. "The European Organ, 1458–1850." The Organ Literature Foundation. Nashua, New Hampshire, 1966.

- Owen, Barbara. "The Mormon Tabernacle Organ: An American Classic" Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1990) ISBN 1555170544

External links

General

- The Pipe Organ

- Worlds Largest Pipe Organs (ranked by number of ranks)

- United States Pipe Organ Directory

- National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR) (UK)

- A Young Person's Guide to the Pipe Organ

- Encyclopedia of Organ Stops over 2000 stop names, with pictures and sound clips.

- Pipe Organ Wiki

- The world's largest organs with photos and stoplists...

- Pipedreams Listen to hundreds of hours of pipe organ music online

- Jeux Soundfonts - Turn your SoundFont-compatible soundcard into a virtual MIDI pipe organ.

- Bach's Organ Tuning

Specific pipe organs

- Pasi Dual-Temperament Organ at Saint Cecilia Cathedral in Omaha, Nebraska

- The Rieger organ in Christchurch, New Zealand

- The Cavaille-Coll organ of St. Sulpice, Paris

- The Wanamaker Organ, Philadelphia

- E.M. Skinner Organ at Severance Hall, Cleveland, Ohio

- Kilgen Organ at St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York

- Aeolian-Skinner Organ at the Riverside Church, New York

- Tabernacle Organ, Salt Lake City, Utah—famous organ of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir

- Aeolian-Skinner and Casavant organs at Community of Christ Auditorium and Temple, Independence, Missouri

- C. B. Fisk organ, La Cathédrale de Lausanne, Switzerland

- Sydney Opera House Grand Organ (PDF introduction and specifications). The World's largest mechanical (tracker) action organ.

- Atlantic City Convention Hall—two organs, one supposedly the largest in the world; and their Preservation Society

- Rildia Bee O'Bryan Cliburn Organ, Broadway Baptist Church, Fort Worth, Texas

- Walt Disney Concert Hall—unique façade

- Photo and video journal of the renovation of the Beckerath organ at Stetson University, DeLand, Florida

- Organ of Cadet Chapel at United States Military Academy, supposedly the largest "working" church organ; complete view of console (First Congregational Church Los Angeles also claims the largest church organ)

- Radio City Music Hall Wurlitzer, largest original theatre organ (4 manuals, 58 ranks)

- Centennial Pipe Organ Chico, CA first pipe organ built on site since the Middle Ages; tenth largest in North America

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: