| |

Lam

Music Sound

Lam

Mor lam sing | Khene

A khene player in Isan

A khene player in Isan

Mor lam (Thai/Isan:

หมอลำ) is an ancient

Lao form of

song in

Laos and Isan (Northeastern Thailand). Mor lam means expert song, or expert singer, referring to

the music or artist respectively. Other

romanisations used include mo lam, maw lam, maw lum,

moh lam and mhor lum. In Laos, the music is known simply as lam

(ລຳ); mor lam (ໝໍລຳ) refers to the singer.

The characteristic feature of lam singing is the use of a flexible

melody which is tailored to the

tones of the words in the text. Traditionally, the tune was developed by the

singer as an interpretation of glawn poems and

accompanied primarily by the

khene, a

free reed mouth organ, but the modern form is most often

composed and uses electrified

instruments. Contemporary forms of the music are also characterised by quick

tempi and rapid delivery, while tempi tend to be slower in traditional forms and

in some Lao genres. Some

consistent characteristics include strong rythmic accompaniment, vocal leaps,

and a conversational style of singing that can be compared to American

rap.

Typically featuring a theme of unrequited

love, mor lam

also reflects the difficulties of life in rural Isan and Laos, leavened with wry

humour. In its heartland performances are an essential part of festivals and

ceremonies, while the music has gained a profile outside its native regions

thanks to the spread of migrant workers, for whom it remains an important

cultural link

with home.

History

In his Traditional Music of the Lao, Terry Miller identifies five

factors which helped to produce the various genres of lam in Isan: animism,

Buddhism, story telling, ritual courtship and male-female competitive folksongs;

these are exemplified by lam phi fa, an nangsue, lam phuen

and lam glawn (for the last two factors) respectively.[1]

Of these, lam phi fa and lam phuen are probably the oldest, while

it was mor lam glawn which was the main ancestor of the commercial mor

lam performed today.

After Siam extended its influence over Laos in the

18th and 19th centuries, the music of Laos began to spread into the Thai

heartlands; even King Mongkut's vice-king Pinklao becoming enamoured of it. But

in 1865, following the vice-king's death, Mongkut banned public performances,

citing the threat it posed to Thai culture and its role in causing drought.[2]

Performance of mor lam thereafter was a largely local affair, confined to events

such as festivals in Isan and Laos. However, as Isan people began to migrate to

the rest of the country, the music spread with them. The first major mor lam

performance of the 20th century in Bangkok took place at the Rajdamnoen Boxing

Stadium in 1946.[3]

Even then, the number of migrant workers from Isan remained fairly small, and

mor lam was paid little attention by the outside world.

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were efforts in both Thailand and Laos to put

the educational aspect of lam to political use. The

USIS in Thailand and both sides in the Lao civil war recruited mor lam singers

to include propaganda in their performances, in the hope of persuading the rural population to support

the cause. The Thai attempt was unsuccessful, taking insufficient account of

performers' practices and audiences' demands, but more success was had in Laos;

the victorious Communists continued to maintain a propaganda troupe even after

the revolution.[4]

Mor lam started to spread in Thailand in the late

1970s and early 1980s, when more and more people left Isan in search of work.

Mor lam performers began to appear on television, led by Banyen Rakgaen, and the genre soon gained a national profile. The music

remains an important link to home for Isan people in the capital, where mor

lam clubs

and karaoke

bars act as meeting places for migrants.

Contemporary mor lam is very different from that of previous

generations. None of the traditional Isan genres is commonly performed today:

instead singers perform three-minute songs combining lam segments with

luk thung

or pop

style sections, while comedians perform skits in between blocks of songs.

Mor lam

sing performances typically consist of medleys of luk thung and

lam songs, with electric instruments dominant and extremely bawdy

presentation. Lam in Laos is much more traditional, having been much less

exposed to Central Thai and western influences. Even there, however, the music

is beginning to change under the influence of Thai culture: instrumentation,

topics and music are all increasingly similar to the modern Isan style.

Thai academic Prayut Wannaudom has argued that modern mor lam is

increasingly sexualised and lacking in the moral teachings which it

traditionally conveyed, and that commercial pressures encourage rapid production

and imitation rather than quality and originality. On the other hand, these

adaptations have allowed mor lam not only to survive, but itself spread

into the rest of Thailand and internationally, validating Isan and Lao culture

and providing role-models for the young.

[5]

Forms

There are many forms of mor lam. There can be no definitive list as

they are not mutually exclusive, while some forms are confined to particular

localities or have different names in different regions. Typically the

categorisation is by region in Laos and by genre

in Isan. The

traditional forms of Isan are historically important, but are now rarely heard:

- lam phi fah (ลำผีฟ้า) a ritual to propitiate

spirits in cases of possession. Musically it derived from lam tang

yao; however, it was performed not by trained musicians but by those

(most commonly old women) who were thought themselves to have been cured by

the ritual.[6]

- mor lam glawn (หมอลำกลอน) a vocal "battle" between the sexes.

In Laos it is known as lam tat. Performances traditionally lasted all

night, and consisted of first two, then three parts:

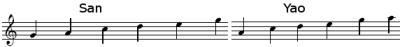

- lam tang san (ลำทางสั้น) ("short form") took up the bulk of

the time, with the singers delivering glawn

poems a few minutes in length, performing alternately for about half an

hour each from evening until about an hour before dawn. They would

pretend gradually to fall in love, sometimes with rather explicit sexual

banter.

- lam tang yao (ลำทางยาว) ("long form"), a representation of

the lovers' parting performed slowly and in a speech rhythm for about a

quarter of an hour.

- lam toei (ลำเต้ย) was introduced in the mid-20th century.

Similar in length to the lam tang yao, it is fast and

light-hearted, with metrical texts falling into three categories:

toei tamada ("normal toei"), using glawn

texts in Isan; toei Pama ("Burmese toei"), using

central or

northern Thai texts and forms; and toei Kong ("Mekong toei"),

again central or northern Thai in origin. It uses the same scale as

lam yao.[7]

- lam jotgae or lam jot (ลำโจทย์แก้ or ลำโจทย์) is a variant

of lam glawn formerly popular in the Khon Kaen area, in which the

singers (often both male) asked one another questions on general knowledge

topics religion, geography, history etc. trying to catch out their

opponent.

- mor lam mu (หมอลำหมู่) folk opera, developed in the mid-20th

century. Lam mu is visually similar to Central Thai

likay, but the subject matter (mainly Jataka stories) derived from

lam rueang (the subgenre of lam phuen) and the music from

lam tang yao. It was originally more serious than lam plern and

required more skilled performers, but in the late 20th century the two

converged to a style strongly influenced by Central Thai and western popular

music and dance. Both have now declined in popularity and are now rare.[8]

- mor lam plern (หมอลำเพลิน) a celebratory narrative, performed

by a group. It originated around the same time as lam mu, but used a

more populist blend of song and dance. The material consisted of metrical

verses sung in the yao scale, often with a speech-rhythm

introduction.[9]

- lam phuen (ลำพื้น) recital of local

legends or Jataka

stories, usually by a male singer, with khene accompaniment. In the subgenre

of lam rueang (ลำเรื่อง), sometimes performed by women, the singer acts out

the various characters in costume. Performance of one complete story can

last for one or two whole nights. This genre is now extremely rare, and may

be extinct.[10]

Isan has regional styles, but these are styles of performance rather than

separate genres. The most important of the styles were Khon Kaen and Ubon, each

taking their cue from the dominant form of lam glawn in their area: the lam

jotgae of Khon Kaen, with its role of displaying and passing on knowledge in

various fields, led to a choppy, recitative-style delivery, while the love

stories of Ubon promoted a slower and more fluent style. In the latter half of

the 20th century the Ubon style came to dominate; the adaptation of Khon Kaen

material to imitate the Ubon style was sometimes called the Chaiyaphum style.[11]

The Lao regional

styles are divided into the southern and central styles (lam) and the

northern styles (khap). The northern styles are more distinct as the

terrain of northern Laos has made communications there particularly difficult,

while in southern and central Laos cross-fertilisation has been much easier.

Northern Lao singers typically perform only one style, but those in the south

can often perform several regional styles as well as some genres imported from

Isan.[12]

The main Lao styles are:[13]

- Lam Sithandone (also called Lam Si Pan Don), from

Champassak is similar in style to the lam glawn of Ubon. It

is.accompanied by a solo khene, playing in a san mode, while the

vocal line shifts between san and yao scales. The rhythm of

the vocal line is also indeterminate, beginning in speech rhythm and

shifting to a metrical rhythm.

- Lam Som is rarely performed and may now be extinct. From

Champassak, the style is hexatonic, using the yao scale plus a

supertonic C, making a scale of A-B-C-D-E-G. It uses speech rhythm in the

vocal line, with a slow solo khene accompaniment in meter. It is similar to

Isan's lam phuen. Both Lam Som and Lam Sithandone lack

the descending shape of the vocal line used in the other southern Lao

styles.

- Lam Khon Savane from Savannakhet is one of the most widespread

genres. It uses the san scale, with a descending vocal line over a

more rigidly metrical ensemble accompaniment. Ban Xoc and Mahaxay

are musically very similar, but Ban Xoc is usually performed only on

ceremonial occasions while Mahaxay is distinguished by a long high

note preceding each descent of the vocal line.

- Lam Phu Thai uses the yao scale, with a descending vocal

line and ensemble accompaniment in meter.

- Lam Tang Vay is a Lao version of

Mon-Khmer

music, with a descending ensemble accompaniment.

- Lam Saravane is also of Mon-Khmer orign. It uses the yao

scale. The descending vocal line is in speech rhythm, while the khene and

drum accompaniment is in meter.

- Khap Thum Luang Phrabang is related to the court music of

Luang Phrabang, but transformed into a folk-song style. The singer and

audience alternately sing lines to a set melody, accompanied by an ensemble.

- Khap Xieng Khouang (also called Khap Phuan) uses the

yao scale and is typically sung metrically by male singers and

non-metrically by women.

- Khap Ngeum uses the yao scale. It alternates declaimed

line from the singer and non-metrical khene passages, at a pace slow enough

to allow improvisation.

- Khap Sam Neua uses the yao scale. Singers are accompanied

by a solo khene, declaiming lines each ending in a cadence.

- Khap Thai Dam

Performers

Traditionally, young mor lam were taught by established artists,

paying them for their teaching with money or in kind. The education focussed on

memorising the texts of the verses to be

sung; these texts could be passed on orally or in writing, but they always came

from a written source. Since only men had access to education, it was only men

who wrote the texts. The musical education was solely by imitation.

Khaen-players

typically had no formal training, learning the basics of playing from friends or

relatives and thereafter again relying on imitation.[14]

With the decline of the traditional genres this system has fallen into disuse;

the emphasis on singing ability (or looks) is greater, while the lyrics of a

brief modern song present no particular challenge of memorisation.

The social status of mor lam is ambiguous. Even in the Isan heartland,

Miller notes a clear division between the attitudes of rural and urban people:

the former see mor lam as, "teacher, entertainer, moral force, and

preserver of tradition", while the latter, "hold mawlum singers in low esteem,

calling them country bumpkins, reactionaries, and relegating them to among the

lower classes since they make their money by singing and dancing".[15]

Performance

A live performance of mor lam sing.

A live performance of mor lam sing.

In Laos, lam

may be performed standing (lam yuen) or sitting (lam nang).

Northern lam is typically lam yuen and southern lam is

typically lam nang. In

Isan lam was

traditionally performed seated, with a small audience surrounding the singer,

but over the latter half of the

20th

century the introduction of stages and amplification allowed a shift to

standing performances in front of a larger audience.[16]

Live performances are now often large-scale events, involving several

singers, a

dance troupe and

comedians. The

dancers (or hang khreuang) in particular often wear spectacular

costumes, while the singers may go through several costume changes in the course

of a performance. Additionally, smaller-scale, informal performances are common

at festivals, temple fairs and ceremonies such as funerals and weddings.

These performances often include

improvised material between songs and passages of teasing dialogue (Isan สอย,

soi) between the singer and members of the audience.

Characteristics

Instruments

The traditional instruments of mor lam are:

Many genres (including the khap of northern Laos and lam glawn

and lam phuen in Isan) were traditionally accompanied only by the khene,

but ensembles have become more common. Most commercial artists now use at least

some electric instruments, most often a

keyboard

set up to sound like a

1960s Farfisa-style

organ;

electric guitars are also common. Other western instruments are also

becoming popular, such as the

saxophone

and the drum

kit.

Music

Lam singing is characterised by the adaptation of the [vocal line to

fit the tones of the words used.[17] It also features staccato articulation and rapid shifting between the limited number of

notes in the scale

being used, commonly delivering around four syllables per second.[18]

There are two

pentatonic scales, each of which roughly corresponds to intervals of a western

diatonic major scale as follows:

The actual

pitches used vary according to the particular khene accompanying the singer.[19]

The khene itself is played in one of six

modes

based on the scale being used.[20]

Because Thai and Lao do not include phonemic stress, the rhythm used in their poetry is demarcative, i.e. based on the

number of syllables rather than on the number of stresses.[21]

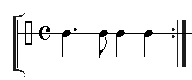

In glawn

verse (the most

common form of traditional lam text) there are seven basic syllables in

each line, divided into three and four syllable

hemistiches. When combined with the musical beat, this produces a natural rhythm

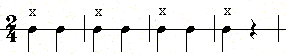

of four on-beat syllables, three off-beat syllables, and a final one beat rest:

In actual practice this pattern is complicated by the subdivision of beats

into even or

dotted two-syllable pairs and the addition of prefix syllables which occupy the

rest at the end of the previous line; each line may therefore include eleven or

twelve actual syllables.[22] In the modern form, there are sudden tempo changes

from the slow introduction to the faster main section of the song. Almost every

contemporary mor lam song features the following

bass rhythm,

which is often ornamented

melodically or

rhythmically, such as by dividing the

crotchets into quavers:

The ching normally play a

syncopated rhythm on the off-beat,

giving the music a characteristically quick rhythm and tinny sound.

Content

Mor lam was traditionally sung in the

Lao or Isan language. The subject matter varied according to the genre: love in

the lam glawn of Ubon; general knowledge in the lam jot of Khon Kaen; or Jataka

stories in lam phun. The most common verse form was the four-line glawn stanza

with seven main syllables per line, although in Khon Kaen the technical subject

matter led to the use of a free-form series of individual lines, called glawn

gap.[23]

In Laos, it is the regional styles which determine the form of the text. Each

style may use a metrical or a speech-rhythm form, or both; where the lines are

metrical, the lam styles typically use seven syllables, as in Isan, while

the khap styles use four or five syllables per line.[24]

The slower pace of some Lao styles allows the singer to improvise the verse, but

otherwise the text is memorised.[25]

In recent decades the Ubon style has come to dominate lam in Isan,

while the Central Thai influence has led to most songs being written in a mix of

Isan and Thai.

Unrequited love is a prominent theme, although this is laced with a considerable

amount of humour. Many songs feature a loyal boy or girl who stays at home in

Isan, while his or her partner goes to work as a migrant labourer in Bangkok and

finds a new, richer lover.

The glawn verses in lam tang san were typically preceded by a

slower, speech-rhythm introduction, which included the words o la naw

("oh my dear", an exhortation to the listeners to pay attention) and often a

summary of the content of the poem.[26]

From this derives the gern (Thai เกริ่น) used in many modern songs: a

slow, sung introduction, generally accompanied by the khene, introducing the

subject of the song, and often including the o la naw. (sample)

The plaeng (Thai เพลง) is a sung

verse, often in

Central Thai. (sample),

while the actual lam (Thai ลำ) appears as a chorus between plaeng

sections. (sample)

Recordings

A mor lam VCD featuring Jintara; the karaoke text, the dancers and the

backdrop are typical of the genre.

A mor lam VCD featuring Jintara; the karaoke text, the dancers and the

backdrop are typical of the genre.

As few mor lam artists write all their own material, many of them are

extremely prolific, producing several

albums each year. Major singers release their recordings on audio tape, CD

and VCD formats. The album may take its name from a title track, but others are simply

given a series number.

Mor lam VCDs can also often be used for

karaoke. A

typical VCD

song

video consists of a performance, a narrative film, or both intercut. The

narrative depicts the subject matter of the song; in some cases, the lead role

in the film is played by the singer. In the performance, the singer performs the

song in front of a static group of dancers, typically female. There may be a

number of these recordings in different costumes, and costumes may be modern or

traditional dress; the singer often wears the same costume in different videos

on the same album. The performance may be outdoors or in a studio; studio

performances are often given a psychedelic animated backdrop.

Videos from Laos tend to be much more basic, with lower production values.

Some of the most popular current artists are

Banyen Rakgan, Chalermphol Malaikham, Jintara Poonlarp, Siriporn Ampaipong, and

Pornsack Songsaeng. In 2001, the first album by Dutch singer Christy Gibson was released.

Notes

- ^ Terry E. Miller,

Traditional Music of the Lao p. 295.

- ^ Miller pp. 38-39.

- ^ Miller p. 40.

- ^ Miller p. 56.

- ^ Prayut Wannaudom,

The Collision between Local Performing Arts and Global Communication, in

case Mawlum

- ^ Garland

Encyclopedia of World Music, p. 329.

- ^ Miller p. 24.

- ^ Garland p. 328.

- ^ Garland p. 328.

- ^ Miller p. 40.

- ^ Miller p. 133.

- ^ Garland p. 341.

- ^ Garland pp. 341-352.

- ^ Miller pp. 43-46.

- ^ Miller p. 61.

- ^ Miller p. 42.

- ^ Miller p. 23.

- ^ Miller p. 142.

- ^ Garland p. 322.

- ^ Garland p. 323

- ^ James N Mosel,

Sound and Rhythm in Thai and English Verse, Pasa lae Nangsue.

Bangkok (1959). p. 31-32.

- ^ Miller p. 104.

- ^ Miller p. 133.

- ^ Garland p. 340.

- ^ Garland p. 342.

- ^ Miller p. 107.

References

External links

Home | Up | List of music genres | African American music | Atonality | Ballet | Blues | Cabaret | Christmas music | Classical music | Computer and video game music | Country music | Crossover | Cumbia | Dance music | Dance music | Dub music | Electronic music | Experimental music | Flamenco | Folk music | Free improvisation | Folk music | Funk | Goth | Heavy metal music | Hip hop music | House music | Jazz | Lam | Mϊsica Popular Brasileira | Mambo | Mazurca | Mbaqanga | Musical theatre | Pop music | Popular music | Punk rock | Rock music | Acid Brass | American march music | Anatolian rock | Andalusi nubah | Background music | Baroque metal | Bass-Pop | Beach music | Beatlesque | Blues ballad | Bomba | Byzantine music | Celtic music | Change ringing | Concert march | Crossover thrash | Dark cabaret | Downtown music | Dronology | Euro disco | Eurobeat | Furniture music | Generative music | Industrial musical | Intermezzo | Lounge music | Martial music | Meditation music | Melodic music | Modern soul | Reggae | World music

Music Sound, v. 2.0, by MultiMedia

This guide is licensed under the GNU

Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia.

|

|