| History of European art music | |

| Medieval | (476 – 1400) |

| Renaissance | (1400 – 1600) |

| Baroque | (1600 – 1760) |

| Classical | (1730 – 1820) |

| Romantic | (1815 – 1910) |

| 20th century | (1900 – 2000) |

| Contemporary classical music | |

Classical music is a broad, somewhat imprecise term, referring to music produced in, or rooted in the traditions of, European art, ecclesiastical and concert music, encompassing a broad period from roughly 1000 to the present day. The central norms of this tradition, according to one school of thought, developed between 1550 and 1825, focusing on what is known as the common practice period.

The term classical music did not appear until the early 19th century, in an attempt to 'canonize' the period from Bach to Beethoven as an era in music parallel to the golden age of sculpture, architecture and art of classical antiquity, (from which of course no music has directly survived). The earliest reference to 'classical music' recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is from about 1836. Since that time the term has developed in common parlance as a simple opposite to popular music.

Contents |

Timeline

According to one school of thought, musical works are best understood in the context of their place in musical history; for adherents to this approach, this is essential to full enjoyment of these works. There is a widely accepted system of dividing the history of classical music composition into stylistic periods. According to this system, the major time divisions are:

- Ancient music - the music generally before the year 476, the approximate time of the fall of the Roman Empire. Most of the extant music from this period is from ancient Greece.

- Medieval, generally before 1450. Monophonic chant, also called plainsong or Gregorian Chant, was the dominant form until about 1100. Polyphonic (multivoiced) music developed from monophonic chant throughout the late Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

- Renaissance, about 1450–1600, characterized by greater use of instrumentation, multiple melodic lines and by the use of the first bass instruments.

- Baroque, about 1600–1750, characterized by the use of complex tonal, rather than modal, counterpoint, and growing popularity of keyboard music (harpsichord and pipe organ).

- Classical, about 1730–1820, an important era which established many of the norms of composition, presentation and style. Also, the classical era is marked by the disappearance of the harpsichord and the clavichord in favour of the piano, which from then on would become the predominant instrument for keyboard performance and composition.

- Romantic, 1815–1910 a period which codified practice, expanded the role of music in cultural life and created institutions for the teaching, performance and preservation of works of music.

- Modern, 1905-1985 a period which represented a crisis in the values of classical music and its role within intellectual life, and the extension of theory and technique. Some theorists, such as Arnold Schoenberg in his essay "Brahms the Progressive," insist that Modernism represents a logical progression from 19th century trends in composition; others hold the opposing point of view, that Modernism represents the rejection or negation of the method of Classical composition.

- 20th century, usually used to describe the wide variety of post-Romantic styles composed through the year 2000, which includes late Romantic, Modern and Post-Modern styles of composition.

- The term contemporary music is sometimes used to describe music composed in the late 20th century through present day.

- The prefix neo is usually used to describe a 20th Century or Contemporary composition written in the style of an earlier period, such as classical, romantic, or modern. So for example, Prokofiev's Classical Symphony is considered a Neo-Classical composition.

The dates are generalizations, since the periods overlapped. Some authorities subdivide the periods further by date or style. However, it should be noted that these categories are to an extent arbitrary; the use of counterpoint and fugue, which is considered characteristic of the Baroque era, was continued by Mozart, who is generally classified as typical of the Classical period, by Beethoven who is often described as straddling the Classical and Romantic periods, and Brahms, who is often classified as Romantic.

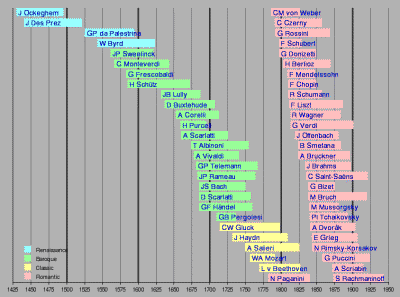

This chart shows a selection of the most famous classical

composers. For a more complete overview see

Graphical timeline for classical composers

Classical music as "music of the classical era"

- Main article: Classical music era

In music history, a different meaning of the term classical music is occasionally used: it designates music from a period in musical history covering approximately Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach to Beethoven – roughly, 1730–1820. When used in this sense, the initial C of Classical music is sometimes capitalized to avoid confusion.

The nature of classical music

Classical music is primarily a written musical tradition, preserved in music notation, as opposed to being transmitted orally, by rote, or in recordings. While there are differences between particular performances of a classical work, a piece of classical music is generally held to transcend any interpretation of it. The use of musical notation is an effective method for transmitting classical music, since the written music contains the technical instructions for performing the work. The written score, however, does not usually contain explicit instructions as to how to interpret the piece, apart from directions for dynamics and tempo; this is left to the discretion of the performers, who are guided by their personal experience and musical education, their knowledge of the work's idiom, and the accumulated body of historic performance practices.

Classical music is meant to be experienced for its own sake, unlike music that serves as an adjunct to other forms of entertainment (although orchestral film music is occasionally treated as classical music). Classical music concerts often take place in a relatively solemn atmosphere, and the audience is usually expected to stay quiet and still to avoid distracting the concentration of other audience members. The performers often dress formally, a practice which is taken as a gesture of respect for the music and the audience, and performers do not normally engage in direct involvement or casual banter with the audience. Private readings of chamber music may take place at more informal domestic occasions.

Its written transmission, along with the veneration bestowed on certain classical works, has led to the expectation that performers will play a work in a way that realizes in detail the original intentions of the composer. Indeed, deviations from the composer's instructions are sometimes condemned as outright ethical lapses. During the 19th century the details that composers put in their scores generally increased. Yet the opposite trend—admiration of performers for new "interpretations" of the composer's work—can be seen, and it is not unknown for a composer to praise a performer for achieving a better realization of the composer's original intent than the composer was able to imagine. Thus, classical music performers often achieve very high reputations for their musicianship, even if they do not compose themselves.

Classical composers often aspire to imbue their music with a very complex relationship between its affective (emotional) content, and the intellectual means by which it is achieved. Many of the most esteemed works of classical music make use of musical development, the process by which a musical germ, idea or motif is repeated in different contexts, or in altered form, so that the mind of the listener consciously or unconsciously compares the different versions. The classical genres of sonata form and fugue employ rigorous forms of musical development. (See also History of sonata form)

Another consequence of the primacy of the composer's written score is that improvisation plays a relatively minor role in classical music, in sharp contrast to traditions like jazz, where improvisation is central. Improvisation in classical music performance was far more common during the Baroque era than in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and recently the performance of such music by modern classical musicians has been enriched by a revival of the old improvisational practices. During the Classical period, Mozart and Beethoven sometimes improvised the cadenzas to their piano concertos (and thereby encouraged others to do so), but they also provided written cadenzas for use by other soloists.

Art music, concert music, and orchestral music are terms sometimes used as synonyms of classical music.

Complexity

Classical works often display great musical complexity through the composer's use of development, modulation (changing of keys), variation rather than exact repetition, musical phrases that are not of even length, counterpoint, polyphony and sophisticated harmony.

Also, many long classical works (from 30 minutes to three hours) are built up from a hierarchy of smaller units: namely phrases, periods, sections, and movements. Schenkerian analysis is a branch of music theory which attempts to distinguish these structural levels.

Emotional content

As with many forms of fine art, classical music often aspires to communicate a transcendent quality of emotion, which expresses something universal about the human condition. While emotional expression is not a property exclusive to classical music, this deeper exploration of emotion arguably allows the best classical music to reach what has been called the "sublime" in art. Many examples often cited in support of this, for instance Beethoven's setting of Friedrich Schiller's poem, Ode to Joy in his 9th symphony, which is often performed at occasions of national liberation or celebration, as in Leonard Bernstein's famously performing the work to mark the collapse of the Berlin Wall, and the Japanese practice of performing it to observe the New Year.

However, some composers, such as Iannis Xenakis, argue that the emotional effect of music on the listeners is arbitrary and therefore the objective complexity or informational content of the piece is paramount.

Instruments

Classical and popular music are often distinguished by their choice of instruments. The instruments used in common practice classical music were mostly invented before the mid-19th century (often, much earlier), and codified in the 18th and 19th centuries. They consist of the instruments found in an orchestra, together with a few other solo instruments (such as the piano, harpsichord, and organ). Electric instruments such as the electric guitar and electric violin play a prominent role in popular music, but of course play no role in classical music before the twentieth century, and only appear occasionally in the classical music of the 20th and 21st centuries. Both classical and popular musicians have experimented in recent decades with electronic instruments such as the synthesizer, electric and digital techniques such as the use of sampled or computer-generated sounds, and the sounds of instruments from other cultures such as the gamelan.

None of the bass instruments existed until the Renaissance. In Medieval Music, instruments are divided in two categories: loud instruments for use outdoors or in church, and quieter instruments for indoor use.

Many instruments which are associated today with popular music used to have important roles in early classical music, such as bagpipes, vilhuela, hurdy-gurdy and some woodwind instruments. On the other hand, the acoustic guitar, for example, which used to be associated mainly with popular music, has gained prominence in classical music through the 19th and 20th centuries.

Finally, while equal temperament became gradually accepted as the dominant musical tuning during the 19th century, different historical temperaments are often used for music from earlier periods. For instance, music of the English Renaissance is often performed in mean tone temperament.

Durability

One criterion that might be said to distinguish works of the classical musical canon is its cultural durability. However, this is not a distinguishing mark of all classical music: works by J. S. Bach (1685–1750) continue to be widely performed and highly regarded, while music by many of Bach's contemporaries, while undoubtedly "classical", is deemed mediocre, and is rarely performed.

Influences between classical and popular music

Classical music has always been influenced by, or taken material from, popular music. Examples include occasional music such as Brahms' use of student drinking songs in his Academic Festival Overture, genres exemplfied by Kurt Weill's The Threepenny Opera, and the influence of jazz on early- and mid-twentieth century composers including Maurice Ravel. Certain postmodern and postminimalist classical composers acknowledge a debt to popular music.

There are also many examples of influence flowing the other way, including popular songs based on classical music, the use to which Pachelbel's Canon has been put since the 1970s, and the musical crossover phenomenon, where classical musicians have achieved success in the popular music arena (one notable example is the "Hooked on Classics" series of recordings made by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in the early 1980s). In fact, it could be argued that the entire genre of film music could be considered part of this influence as well, since it brings orchestral music to vast audiences of moviegoers who might otherwise never choose to listen to such music (albeit for the most part unconsciously).

Classical music and folk music

Composers of classical music have often made use of folk music (music created by untutored musicians, often from a purely oral tradition). Some have done so with an explicit nationalist ideology, others have simply mined folk music for thematic material.

Commercial uses of classical music

Certain staples of classical music are often used commercially (that is, either in advertising or in the soundtracks of movies made for entertainment). In television commercials, several loud, bombastically rhythmic orchestral passages have become cliches, particularly the opening "O Fortuna" of Carl Orff's Carmina Burana; other examples in the same vein are the Dies Irae from the Verdi Requiem, and excerpts of Aaron Copland's "Rodeo".

Similarly, movies often revert to standard, cliched snatches of classical music to represent refinement or opulence: probably the most-often heard piece in this category is Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik.

Classical music in education

Throughout history, parents have often made sure that their children receive classical music training from a young age. Early experience with music provides the basis for more serious study later. For those who desire to become performers, any musical instrument is practically impossible to learn to play at a professional level if not learned in childhood. Some parents pursue music lessons for their children for social reasons or in an effort to instill a useful sense of self-discipline; lessons have also been shown to increase academic performance. Some consider that a degree of knowledge of important works of classical music is part of a good general education.

The 1990s marked the emergence in the United States of research papers and popular books on the so-called Mozart effect: a temporary, small elevation of scores on certain tests as a result of listening to Mozart. The popularized version of the controversial theory was expressed succinctly by a New York Times music columnist: "researchers have determined that listening to Mozart actually makes you smarter." Promoters marketed CDs claimed to induce the effect. Florida passed a law requiring toddlers in state-run schools to listen to classical music every day, and in 1998 the governor of Georgia budgeted $105,000 a year to provide every child born in Georgia with a tape or CD of classical music. One of the original researchers commented "I don't think it can hurt. I'm all for exposing children to wonderful cultural experiences. But I do think the money could be better spent on music education programs."

Related genres

Terms of classical music

For terms relating specifically to the performance of classical music, see the Musical terminology.

Literature

- Norman Lebrecht, When the Music Stops: Managers, Maestros and the Corporate Murder of Classical Music, Simon & Schuster 1996

External links

- Classic Cat – A directory of free classical MP3.

- Classical.net – review, database and mailing-list resource

- Classical Archives – music, artists, composers, MIDI files

- Classical Live Online Radio Europe - List of European online radio stations dedicated to classical music

- ChopinMusic Forum – a community of romantic music lovers

- European Classical Music – chronology and free downloads

- MusicWeb International – CD reviews, composer articles, timelines, concert and book reviews

- ViolinMP3.com Violin Information website, containing several classical music resources and composer guides

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: