The term comes from the Latin punctus contra punctum ("note against note"). The adjectival form contrapuntal shows this Latin source more transparently.

By definition, chords occur when multiple notes sound simultaneously; however, chordal, harmonic, "vertical" features are considered secondary and almost incidental when counterpoint is the predominant textural element. Counterpoint focuses on melodic interaction rather than harmonic effects generated when melodic strands sound together:

- "It is hard to write a beautiful song. It is harder to write several individually beautiful songs that, when sung simultaneously, sound as a more beautiful polyphonic whole. The internal stuctures that create each of the voices, separately must contribute to the emergent structure of the polyphony, which in turn must reinforce and comment on the stuctures of the individual voices. The way that is accomplished in detail is...'counterpoint'." [1]

It was elaborated extensively in the Renaissance period, but composers of the Baroque period brought counterpoint to a kind of culmination, and it may be said that, broadly speaking, harmony then took over as the predominant organising principle in musical composition. The late Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach wrote most of his music incorporating counterpoint, and explicitly and systematically explored the full range of contrapuntal possibilities in such works as The Art of Fugue.

Given the way terminology in music history has evolved, such music created from the Baroque period on is described as contrapuntal, while music from before Baroque times is called polyphonic. Hence, the earlier composer Josquin Des Prez is said to have written polyphonic music.

Homophony, by contrast with polyphony, features music in which chords or vertical intervals work with a single melody without much consideration of the melodic character of the added accompanying elements, or of their melodic interactions with the melody they accompany. As suggested above, most popular music written today is predominantly homophonic — governed by considerations of chord and harmony. But these are only strong general tendencies, and there are many qualifications one could add.

The form or compositional genre known as fugue is perhaps the most complex contrapuntal convention. Other examples include the round (familiar in folk traditions) and the canon.

In musical composition, counterpoint is an essential means for the generation of musical ironies; a melodic fragment, heard alone, may make a particular impression, but when it is heard simultaneously with other melodic ideas, or combined in unexpected ways with itself, as in a canon or fugue, surprising new facets of meaning are revealed. This is a means for bringing about development of a musical idea, revealing it to the listener as conceptually more profound than a merely pleasing melody.

Excellent examples of counterpoint in jazz include Gerry Mulligan's Young Blood and Bill Holman's Invention for Guitar and Trumpet and his Theme and Variations as well as recordings by Stan Getz, Bob Brookmeyer, Johnny Richards and Jimmy Giuffre. [2]

Contents |

Species counterpoint

Species counterpoint is a type of strict counterpoint, developed as a pedagogical tool, in which a student progresses through several "species" of increasing complexity, gradually attaining the ability to write free counterpoint according to the rules at the given time. The idea is at least as old as 1532, when Giovanni Maria Lanfraco described a similar concept in his Scintille di musica. The late 16th century Venetian theorist Zarlino elaborated on the idea in his influential Le institutioni harmoniche, and it was first presented in a codified form in 1619 by Lodovico Zacconi in his Prattica di musica. Zacconi, unlike later theorists, included a few extra contrapuntal techniques as species, for example invertible counterpoint.

By far the most famous pedagogue to use the term, and the one who made it famous, was Johann Fux. In 1725 he published Gradus ad Parnassum (Step by Step Up Mount Parnassus) a work intended to help teach students how to compose, using counterpoint — specifically, the contrapuntal style as practiced by Palestrina in the late 16th century — as the principal technique. Fux described five species:

- Note against note;

- Two notes against one;

- Four notes against one;

- Notes offset against each other (as suspensions);

- All the first four species together, as "florid" counterpoint.

Considerations for all species

Students of species counterpoint usually practice writing counterpoint in all the modes (Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian and Aeolian). The following rules apply to melodic writing in each species, for each part:

- The final must be approached by step. If the final is approached from below, the leading tone must be raised, except in the case of the Phrygian mode. Thus, in the Dorian mode on D, a C# is necessary at the cadence.

- Permitted melodic intervals are the perfect fourth, fifth, and octave, as well as the major and minor second, major and minor third, and ascending minor sixth. When the ascending minor sixth is used it must be immediately followed by motion downwards.

- If writing two skips in the same direction—something which must be done only rarely—the second must be smaller than the first, and the interval between the first and the third note may not be dissonant.

- If writing a skip in one direction, it is best to proceed after the skip with motion in the other direction.

- The interval of a tritone in three notes is to be avoided (for example, an ascending melodic motion F - A - B natural), as is the interval of a seventh in three notes.

And, in all species, the following rules apply concerning the combination of the parts:

- The counterpoint must begin and end on a perfect consonance.

- Contrary motion should predominate.

- The interval of a tenth should not be exceeded between two adjacent parts, unless by necessity.

First species

In first species counterpoint, each note in an added part* (or parts) sounds against one note in the cantus firmus. Notes in all parts are sounded simultaneously, and move against each other simultaneously. The species is said to be expanded if any of the added notes is broken up (simply repeated).

In counterpoint, a "step" is a melodic interval of a half or whole step. A "skip" is an interval of a third or fourth. An interval of a fifth or larger is referred to as a "leap".

A few further rules given by Fux, by study of the Palestrina style, and usually given in the works of later counterpoint pedagogues, are as follows. Some are vague, and since good judgement and taste have been regarded by contrapuntists as more important than strict observance of mechanical rules, there are many more cautions than prohibitions. But some are closer to being mandatory, and are accepted by most authorities.

- Begin and end on either the unison, octave, or fifth, unless the added part is underneath, in which case begin and end only on unison or octave.

- Use no unisons except at the beginning or end.

- Avoid parallel fifths or octaves between any two parts; and avoid "hidden" parallel fifths or octaves (that is, movement by similar motion to a perfect fifth or octave, unless the higher of the parts moves by step).

- Attempt to keep two adjacent parts within a tenth of each other, unless an exceptionally pleasing line can be written outside of that range.

- Avoid moving in parallel thirds or sixths for too long.

- Avoid having both parts move in the same direction by skip.

- Attempt to have as much contrary motion as possible.

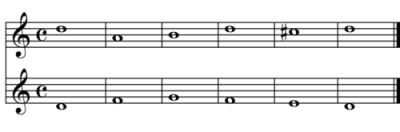

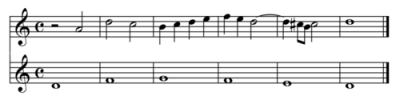

In the following examples, all in two voices, the cantus firmus — the given part — is in the lower voice. The same cantus firmus is used for each, and each is in the Dorian mode.

Short example of "First Species"

counterpoint

Short example of "First Species"

counterpoint

Second species

In second species counterpoint, two notes in the added part (or parts) work against each longer note in the given part. The species is said to be expanded if one of the two shorter notes differs in length from the other.

Additional considerations in second species counterpoint are as follows, and are in addition to the considerations for first species:

- It is permissible to begin on an upbeat, leaving a half-rest in the added voice.

- The accented beat must have only consonance (perfect or imperfect). The unaccented beat may have dissonance, but only as a passing tone, i.e. it must be approached and left by step in the same direction.

- Avoid the interval of the unison except at the beginning or end of the example, except that it may occur on the unaccented portion of the bar.

- Use caution with successive accented perfect fifths or octaves. They must not be used as part of a sequential pattern.

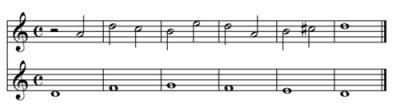

Short example of "Second Species"

counterpoint

Short example of "Second Species"

counterpoint

Third species

In third species counterpoint, four (or three) notes move against each longer note in the given part. As with second species, it is expanded if the shorter notes vary in length among themselves.

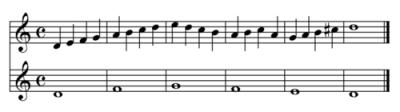

Short example of "Third Species"

counterpoint

Short example of "Third Species"

counterpoint

Fourth species

In fourth species counterpoint, a note is sustained or suspended in an added part while notes move against it in the given part, creating a dissonance, followed by the suspended note then changing (and "catching up") to create a subsequent consonance with the note in the given part as it continues to sound. Fourth species counterpoint is said to be expanded when the added-part notes vary in length from each other. The technique requires chains of notes sustained across the boundaries determined by beat, and so creates syncopation.

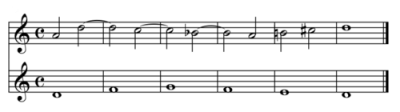

Short example of "Fourth Species"

counterpoint

Short example of "Fourth Species"

counterpoint

Florid counterpoint

In fifth species counterpoint, sometimes called florid counterpoint, the other four species of counterpoint are combined within the added part (or added parts). In the example, the first and second bars are second species, the third bar is third species, and the fourth and fifth bars are third and embellished fourth species.

Short example of "Florid" counterpoint

Short example of "Florid" counterpoint

General notes

It is a common and pedantic misconception that counterpoint is defined by these five species, and therefore anything that does not follow the strict rules of the five species is not counterpoint. This is not true; although much contrapuntal music of the common practice period indeed adheres to the rules, there are exceptions. Fux's book and its concept of "species" was purely a method of teaching counterpoint, not a definitive or rigidly prescriptive set of rules for it. He arrived at his method of teaching (or so he believed, at least) by examining the works of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, an important late 16th-century composer who in Fux's time was held in the highest esteem as a contrapuntalist. Works in the contrapuntal style of the 16th century—the "prima pratica" or "stile antico," it was called by modernist composers then—were often said by Fux's contemporaries to be in "Palestrina style." Indeed, Fux's treatise is a rather accurate compendium of Palestrina's techniques.

* (Note: in counterpoint, the parts or individual melodic strands are often called voices, even if the music is thought of as instrumental.)

Contrapuntal derivations

Since the Renaissance period in European music, much music which is considered contrapuntal has been written in imitative counterpoint. In imitative counterpoint, two or more voices enter at different times, and (especially when entering) each voice repeats some version of the same melodic element. The fantasia, the ricercar, and later, the fugue (the contrapuntal form par excellence) all feature imitative counterpoint, which also frequently appears in choral works such as motets and madrigals. Imitative counterpoint has spawned a number of devices that composers have turned to in order to give their works both mathematical rigor and expressive range. Some of these devices include:

- Inversion: The inverse of a given fragment of melody is the fragment turned upside down – so if the original fragment has a rising major third (see interval), the inverted fragment has a falling major (or perhaps minor) third. (Compare, in twelve tone technique, the inversion of the tone row, which is the so-called prime series turned upside down.) In a completely separate sense, a contrapuntal inversion of melodies being simultaneously sounded by voices is the subsequent switching of the melodies between voices, so that for example an upper-voice melody is now sounded in some lower voice, and vice versa.

- Retrograde refers to the contrapuntal device whereby notes in an imitative voice sound backwards in relation to their order in the original.

- Retrograde inversion is where the imitative voice sounds notes both backwards and upside down.

- Augmentation is when in one of the parts in imitative counterpoint the notes are extended in duration compared to the rate at which they were sounded when introduced.

- Diminution is when in one of the parts in imitative counterpoint the notes are reduced in duration compared to the rate at which they were sounded when introduced.

Dissonant counterpoint

Dissonant counterpoint was first theorized by Charles Seeger as "at first purely a school-room discipline," consisting of species counterpoint but with all the traditional rules reversed. First species counterpoint is required to be all dissonances, establishing "dissonance, rather than consonance, as the rule," and consonances are "resolved" through a skip, not step. He wrote that "the effect of this discipline" was "one of purification." Other aspects of composition, such as rhythm, could be "dissonated" by applying the same principle (Charles Seeger, "On Dissonant Counterpoint," Modern Music 7, no. 4 (June-July 1930): 25-26).

Seeger was not the first to employ dissonant counterpoint, but was the first to theorize and promote it. Other composers who have used dissonant counterpoint, if not in the exact manner prescribed by Charles Seeger, include Ruth Crawford-Seeger, Carl Ruggles, Dane Rudhyar, and Arnold Schoenberg.

Sources

- ^ Rahn, John (2000). Music Inside Out: Going Too Far in Musical Essays, p.177. ISBN 9057013320.

- ^ Corozine, Vince (2002). Arranging Music for the Real World: Classical and Commercial Aspects, p.34. ISBN 0786649615.

External links

- ntoll.org: Species Counterpoint by Nicholas H. Tollervey

- University of Montreal: Principles of Counterpoint by Alan Belkin

- Orima: The History of Experimental Music in Northern California: On Dissonant Counterpoint by David Nicholls from his American Experimental Music: 1890-1940

- Dane Rudhyar's Vision of American Dissonance article from American Music (Summer 1999), by Carol J. Oja

- Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary: Dissonant counterpoint examples and definition

- De-Mystifying Tonal Counterpoint or How to Overcome Your Fear of Composing Counterpoint Exercises by Christopher Dylan Bailey, composer at Columbia University

- New "Olde-Musicke" Tonal Midis and MP3s Composed by Bob Fink "in classical, baroque or other old or "counterpoint" styles"

- A Further Note on Early Harmony: The Role of the Drone & Counterpoint in the Development of Harmony from the Appendix to Origin of Music, 3rd ed., by Bob Fink (1980)[1]

Categories: Musical terminology

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: