Lyrics in Carnatic music are largely devotional; most of the songs are addressed to the Hindu deities. There are, besides, a lot of songs emphasising love and other social issues which have been composed in Carnatic music, although some of them, especially with the 'Raga' (emotion) of love, continue to be composed and are widely popular, that rest on the concept of sublimation of human emotions for union with the divine. Thus, for instance, a young woman in a modern classical composition, will be yearning for one of the deities, such as Krishna, as her 'lover - the purpose of such musical pieces being at once to provide an outlet for human emotions and, unlike in the normal run of motion pictures, to address God rather than another human being. Carnatic music as a classical form is always thus required to be a culturally elevating medium.

As with all Indian classical music, the two main components of Carnatic music are raga - a melodic pattern, and tala - a rhythmic pattern. (One might want to read these pages before proceeding.)

Contents |

History

Main article: History of Carnatic music

Carnatic music, whose foundations go back to Vedic times, began as a spiritual ritual of early Hinduism. Hindustani music and Carnatic music were one and the same, out of the Sama Veda tradition, until the Islamic invasions of North India in the late 12th and early 13th century. From the 13th century onwards, there was a divergence in the forms of Indian music — the northern style being influenced by Persian/Arabic music.

Carnatic music is named after the region in southern India what is today known as Karnataka. Carnatic was the anglicized spelling of Karnataka and hence it has come to be known as Carnatic Music. The great Kannada composer Shri. Purandara Dasa is known as the Sangitapitamaha or 'Father of Karnatik music'. The roots of Carnatic music was sown during the Vijayanagar Empire by the Kannada Haridasa movement of Vyasaraja, Purandaradasa, Kanakadasa and others.

It is said that Purandara Dasa laid out the basic learning structure and framework for imparting carnatic music. The learning structure is arranged in the increasing order of the complexity. The lessons start with Sarale varase, meaning simple patterns and is having no defined ends. Though a good authority in the 72 parent ragas and related raga, taana, and pallavi, swara prasthara, is a mark of a professional - by no measure that's an end

Theory

Śruti (ಶೃತಿ, श्रुति, శ్రుతి)

Śruti in Indian music is the rough equivalent of a tonic (or less precisely key) in Western music; it is the note from which all the others are derived. Traditionally, there are twenty-two śrutis in Carnatic music, but over the years several of them have converged, so that now they are but the chromatic scale.

The solfege

Description

The solfege of Carnatic music is "sa-ri-ga-ma-pa-da-ni" (compare with the Hindustani sargam: sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni). These names are abbreviations of the longer names shadjam, rishabham, gandharam. madhyamam, panchamam, dhaivatam and nishadam. Unlike other music systems, every member of the solfege (called a swara) may have up to three variants. The exceptions are shadjam and panchamam (the tonic and the dominant in Western music), which have only one form, and madhyamam, which has only two forms (the subdominant). In one scale, or ragam, there is usually only one variant of each note present, except in "light" ragas, such as Behag, in which, for artistic effect, there may be two, one on the way up (in the arohanam) and another on the way down (in the avarohan). A raga may have five, six or seven notes on the way up, and five, six or seven notes on the way down.

The Carnatic solfege in different scripts

In Indian languages, most of whose alphabets are abugidas (q.v.), the solfege is written with the characters for Sa, Ri, Ga, Pa, Da and Ni. Because Carnatic music is very rarely performed by people from North India, the alphabets given here are primarily those of Dravidian, i.e., South Indian, languages.

| Sound | Full Name | Devanagari | Telugu | Tamil | Kannada | Malayalam | Roman alphabet | Value and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sa | Shadja | स | స | ஸ | ಸ | സ | s | Only one possible value. Sometimes referred to as the 'mother' note - all Ragas have this note. |

| ri | Rishaba | रि | రి | ரி | ರಿ | രി | r | Three possible values. |

| ga | Gāndhāra | ग | గ | க | ಗ | ഗ | g | Three possible values (one of which coindices with the third ri). |

| ma | Madhyama | म | మ | ம | ಮ | മ | m | Two possible values. |

| pa | Panchama | प | ప | ப | ಪ | പ | p | Only one possible value. Sometimes referred to as the 'father', though not all ragas have this note. |

| dha | Dhaivatha | ध | ద | த | ದ | ധ | d | Three possible values. |

| ni | Nishāda | नि | ని | நி | ನಿ | നി | n | Three possible values (one of which coincides with the third dha). |

The raga system

Main article: raga

Melakartas

In Carnatic music, the sampurna ragas (the ones that have seven notes in their scales) are classified into the melakarta system, which groups them according to the kinds of notes that they have. There are seventy-two melakarta ragas, thirty-six of whose subdominant is a perfect fourth from the tonic, thirty-six of whose subdominant is an augmented fourth from the tonic. The ragas are grouped into sets of six, called chakras ("wheels", though actually sectors in the conventional representation) grouped according to the supertonic and mediant scale degrees. This scheme can very well understood and remembered by Katapayadi sankhya

Classification

Ragas may be divided into two classes: janaka ragas ("parent ragas") and janya ragas ("child ragas"). Janaka raga is synonymous with melakarta (because the melakarta ragas each have seven notes in their scale, and use each note only once). Janya ragas are subclassified into various categories themselves.

The tala system

In carnatic music, singers keep the beat by moving their hands in specified patterns. These patterns are called talas. All of the which are formed with three basic movements: lowering the palm of the hand onto the thigh, lowering a specified number of fingers in sequence (starting from the little finger), and turning the hand over. These basic movements are grouped into three kinds of units: the laghu (lowering the palm and then the fingers, notated as 1), the dhrutam (lowering the palm and turning it over, notated as 0), and the anudhrutam (just lowering the palm, notated as ☾). Only these units are used.

There are seven kinds of talas which can be formed from the laghu, dhrtam, and anudhrtam:

- Dhruva tala 1 0 1 1

- Matya tala 1 0 1

- Rupaka tala 0 1

- Jhampa tala 1 ☾ 0

- Triputa tala 1 0 0

- Ata tala 1 1 0 0

- Eka tala 1

How many fingers must be lowered in a laghu is determined by the jathi, a number showing how many fingers to lower. It can only be 3, 4, 5, 7, or 9. (For numbers greater than five, the "sixth finger" is the same as the little finger.) Five jathis times seven patterns gives thirty-five possible talas.

Compositions

Composers of Carnatic music were often inspired by devotion and were usually scholars proficient in Kannada, Telugu,Tamil and Sanskrit. They would usually include a signature, called a mudra, in their compositions. For example, all songs by Tyagaraja have the word Tyāgarāja in them, all songs by Muthuswami Dikshitar (who composed in Sanskrit) have the words guru guha in them, songs by Syama Sastri have the words "Syama Krishna" in them and Purandaradasa, the father of Karnatik music (who composed in Kannada), used the signature 'purandara vitala'.

Kīrtanas

Carnatic songs are varied in structure and style, but generally consist of three verses:

- Pallavi (ಪಲ್ಲವಿ,पल्लवि,పల్లవి). This is the equivalent of a refrain in Western music. Two lines.

- Anupallavi (ಅನುಪಲ್ಲವಿ, अनुपल्लवि,అనుపల్లవి). The second verse. Also two lines.

- Charana (ಚರಣ, चरणं,చరణం). The final (and longest) verse that wraps up the song. The Charanam usually borrows patterns from the Anupallavi. Usually three lines.

This kind of song is called a keerthanam (कीर्तनं). But this is only one possible structure for a keerthanam. Some keerthanas, such as Sārasamuki sakala bhāgyadē have a verse between the anupallavi and the caraṇam, called the ciṭṭaswaram (चिट्टस्वरं). This verse consists only of notes, and has no words. Still others, such as Rāmacandram bhāvayāmi have a verse at the end of the caraṇam, called the madhyamakālam. It is sung immediately after the caraṇam, but at double speed.

Varnas

A Varna(ವಣ೯) is a special kind of song which tells you everything about a raga; not just the scale, but also which notes to stress, how to approach a certain note, classical and characteristic phrases, etc. A varna has a pallavi, an anupallavi, a muktāyi swara, whose function is identical to that of the chiTTeswara(ಚಿಟ್ಟೆ ಸ್ವರ) in a kriti, a charaNa, and chiTTeswaras, after each of which the charaNa is repeated:

- Pallavi (ಪಲ್ಲವಿ)

- Anupallavi (ಅನುಪಲ್ಲವಿ)

- Muktāyi swara(ಮುಕ್ತಾಯಿ ಸ್ವರ)

- Charana(ಚರಣ)

- ChiTTeswara (ಚಿಟ್ಟೆ ಸ್ವರ)

- First

- Second

- Third

- et cetera

There are many more kinds of songs such as geethams and swarajatis, but for lack of room, they will not be explained here.

Special compositions

Some special sets of compositions deserve to be noted here, the Pancaratna Kīrtanas (पञ्चरत्नकृति, పంచరత్న క్రుతులు) of Tyagaraja, Kamalamba Navavarna Kritis and Navagraha Kritis(నవగ్రహ క్రుతులు) of Muttusvami Dikshitar.

The Pancaratna Kīrtanas (lit. five gems), composed by Tyagaraja in Sanskrit and Telugu, are a set of five compositions regarded as the masterpieces of the great composer. The first one is in Sanskrit, while the rest are in Telugu. They deviate from conventional structure in that they all have between eight and twelve caraṇas. Sādincanē Ō Manasā, the third of the compositions, deviates even more in that after the anupallavi, there is a short phrase after which the caraṇas are sung. Also, instead of repeating the pallavi after each caraṇam, the phrase between the anupallavi and the first caraṇam is sung.

Dikshitar's nava-aavarana-kritis (literally,'nine-veils compositions') are addressed to the supreme divine in its female principle according to which the male-female division, so universally observed in life forms, is essentially the manifestation of one and the same Divinity. The Navagraha kritis are respectively sung in devotion to the Sun, the Moon, and the other planets, which thus popularises in a subtle manner, that Man owes his very existence to a highly remote chance - maybe one in a billion - for living on earth in a precisely conducive environment of celestial configuration, and he must understand this fact with his rational and spiritual makeup, with Kritis of this unique type. This set of Dikshitar creations, like most of his others, are considered remarkable for recalling the sastra-ic aspects - the scriptural profunditions of Hindu religious philosophy - and the lay listener either sings them with implicit faith either even without an understanding their meaning, or with some effort, gets to know by attending scholarly lecture-cum-demonstrations and/or reading books or papers (nowadays rather widely available online on the WWW.). It is said that the mature Carnatic musician sees the multidimensional charm of the special and non-special Kritis that are at once rich musically, educative philosophically, and disciplining religiously to the singer, player and the musician, provided the necessary inputs at appreciating the many charms.

Another prolific composer in Carnatic Music, King Swati Tirunal, too, has composed hundreds of songs which are particularly noted for their lyrical charm, and Swati too has to his credit a set of special compositions which are sung on the festival occasion of 'Navaratri' (lit., nine nights) in which three days each are devoted to the three deities, Durga, Lakshmi and Sarasvati.

Improvisation

There are four main types of improvisation in Carnatic music:

- Raga Alapana ( राग आलापना, రాగ ఆలాపన ) This is usually performed before a song. It is, as you may expect, always sung in the ragam of the song. It is a slow improvisation with no rhythm, and is supposed to tune the listener's mind to the appropriate ragam by reminding him/her of the specific nuances, before the singer plunges into the song. Theoretically, this ought to be the easiest type of improvisation, since the rules are so few, but in fact, it takes much skill to sing a pleasing, comprehensive (in the sense of giving a "feel for the ragam") and, most importantly, original ragam.

- Niraval ( निरवल्, నిరవల ) This is usually performed by the more advanced concert artists and consists of singing one or two lines of a song repeatedly, but with improvised elaborations. (A similar thing used to be done in Baroque music).

- (Kalpana)swaram ( [कल्पना]स्वरं,కల్పన సవరం ) The most elementary type of improvisation, usually taught before any other form of improvisation. It consists of singing a pattern of notes which finishes on the beat and the note just before the beat and the note on which the song starts. The swara pattern should adhere to the original raga's swara pattern, which is called as "arohana-avarohana"

- Taanam ( तानं, తానం ) This form of improvisation was originally developed for the veena and consists of repeating the word anantham (अनंतं) ("endless") in an improvised tune. The name thaanam comes from a false splitting of anantham repeated. When the word anantham is repeated, i.e., "anantham-anantham", the laws of sandhi dictate that the consonant at the end of the first word be dropped, hence "ananthaanantham" When the rule is applied to a long string of ananthams, you get "ananthaananthaananthaananthaa..." which got falsely split as "thaananthaananthaanan...", or "thaanamthaanamthaanam...".

- (Ragam Thanam) Pallavi ( [रागा तानं] पल्लवि )

-

- రాగం తానం పల్లవి

- பல்லவி எந்றால் பதம், லயம், விஞாஸம்

-

- Pallavi means: words (padam), rhythm (layam) and improvisation (viñāsam)

- This is a composite form of improvisation. It consists of Ragam, Thanam, then a line sung twice, and Niraval. After Niraval, the line is sung again, twice, then sung once at half the speed, then twice at regular speed, then four times at twice the speed.

Concerts

Instruments

A Carnatic music performance by Balamurali Krishna,

clockwise from left Perunna G. Harikumar(Mridangom),Manjoor

Unnikrishnan(Ghatam), Mavelikkara Sathees Chandran(Violin)

A Carnatic music performance by Balamurali Krishna,

clockwise from left Perunna G. Harikumar(Mridangom),Manjoor

Unnikrishnan(Ghatam), Mavelikkara Sathees Chandran(Violin)

Carnatic concerts are usually performed by a small ensemble of musicians, who usually (but not always) meet only on the stage. The group usually has a vocalist, a primary instrumentalist, and a percussionist, in that order of importance. Primary instruments are usually string instruments, such as the vīṇā and violin, although wind instruments such the flute may also be used.[1]

The importance given to the vocalist in performances is a reflection of Carnatic music's focus on the singer and its rooting in the poetry of the Sama Veda; any instrumental rendition is merely a transcription of the vocal line. However, in recent years, purely instrumental concerts have become popular.

Support

The tambura, the most common kind of drone instrument, is traditionally used at concerts to remind the singer of the tonic, so that the singer may stay in tune throughout the performance. However, not only is the tambura unwieldy, it is also fragile, and is thus increasingly being replaced by the more compact śruti box (also known as the "electronic tambura").

The usual interacting and active accompaniments are Violin [first adopted into Carnatic music by Baluswami Dikshitar brother of Muthuswami Dikshitar], Mridangam [two-sided percussion instrument played horizontally] and Ghatam [hollow mud pot] or a Khanjira. It is not so common to have a veena as an accompaniment. Other possible accompaniments that one can see are the Morsing and the Kunnakol. Besides playing along with the main vocalist, the violinist also gets the chance to take part in the improvisation. The violinist's role is a bit tough as the violinist needs to play on-the-fly anything that is chosen by the main artiste. The accompanying violinist will be expected to match skills with the Vocalist in a few places. The violinist is expected to play both the melody and the mathematical aspects of the vocalist.

The violin has also established itself as a main instrument.

The vocalist and the violinist take turns while elaborating or while exhibiting creativity in sections like Niraval, Kalpana swaram and the like.

The percussion support will play an active role on the Rhythm aspect.

Percussion

Percussion instruments, such as the mridangam, ghatam, kanjira are used to help the singer in keeping the beat, but they may also improvise. The morsing is also seen in some concerts and it accompanies the main percussion instrument and plays almost in a contrapuntal fashion along with the beats.

Content

Carnatic concerts, these days, last for typically no more than 3 hours. The artist may render about 10 to 15 songs. The richness and depth of artistry of the content may vary greatly based on the artist and to an extent based on what the audience request.

The stage

Prayer

Concerts almost always start with a song in praise of Ganapathi, the remover of obstacles. For this, songs such as vināyakā ninnuvinā brōcuḍaku and gam gaṇapatē, among many, many others, are common. But it is not uncommon to find concerts that start with Varnams and then have a song on Ganapathi.

Varnam

Most artists decide to keep the Varnam in a sampoorna raga. A Varnam typically lasts for about 6 to 12 minutes. Since Varnams are performed during the initial part of the concert, some people try to keep the Varnam in a bright raga (can be roughly translated to Major scales) like Kalyani or Dheerasankarabharanam).

Keerthanams

In the middle are a variety of compositions, generally contrasting in emotion. Sometimes, a rāgam is sung before each of these compositions, and kalpanāswaram is sung after. Usually there are several keerthanams composed by the trinity and others sung during this phase.

Thani

Almost always all Carnatic concerts nowadays have only one Thani Avarthanam. This is kept almost towards the end of the concert. The Thani Avarthanam begins after the violinist and the vocalist (or the main performer in case of an instrumental concert) have completed their kalpana swaras or niraval and usually the vocalist nods at the percussionist to start his Thani. In case there are two or more percussion instruments, each of the percussionists start by playing a lengthy piece of beats called an Avarthanam. The length of the Avarthanam goes on reducing in a mathematical proportion as the percussionists take turn. Towards the end of the Thani Avarthanam they start playing together and the song ends with the main performer singing the line that was used for Kalpana / Niraval.

Ragam Tanam Pallavi

Some experienced artists may do a Ragam Tanam Pallavi instead of a Keerthanam as the main piece of the Concert. Nevertheless, a Ragam Tanam Pallavi exposition will also comprise of a Thani.

Tukkada

After a heavy dose of musically complex keerthanas the artists perform short, light and usually fast numbers. The recent trend has been that some of these are based on Hindustani Ragas. tillanas and Javalis are sung during this phase. There would roughly be around 3 to 5 tukkadas.

Mangalam

Almost always the very last song of a Concert is set to a raga like Sourashtram or Madhyamavathi (a happy sounding raga). The mangalam usually is 'continued' without a pause after the end of the penultimate song. Most artists thank the audience by means of a song specifically meant to thank the audience for their support.

The audience

The typical audience in the average South Indian Carnatic concert is in the 50+ age group with the exception of some young students of music and some journalists who have come to write reviews about the concert. But the majority of the audience have a very decent understanding of Carnatic music and will probably be able to help you with if you have doubts. It is not uncommon to find some of them noting down the name, tala and raga of the song being sung. It is important to note that only a very few artists tell out the name, tala and raga of the song they are performing. Those popular amongst the masses usually tell out the raga and the tala of the song. When not told, it is up to the listener to identify the raga and tala.

It is also easy to see the audience tapping out the tala in sync with the artist's performance. It would be frowned at by the people sitting next to you to be seen tapping the wrong tala and some artists might even interrupt the entire concert or even get angry![2]. For the same reason most sabhas want to play it safe by reserving the first two or three rows of seats in the auditorium to only VIPs.

As and when the artist exhibits creativity, the audience acknowledge it by clapping their hands. With experienced artists, towards the middle of the concert, requests start flowing in. The artist usually plays the request and it helps in exhibiting the artist's broad knowledge of the several thousand kritis that are in existence. However it is generally a norm for the rasika to meet the artist before hand if the rasika wishes a complex kriti (like one of the Pancharatna Kritis) or a Ragam Tanam Pallavi to be done.

It is amusing to find that some of the crowd also start leaving when the Thani has begun.

The teaching of Carnatic music

Traditionally, a student of Carnatic music goes to the house of the teacher for lessons. Both student and teacher sit cross-legged on the floor (usually on a mat). The teacher either starts playing the tambūrā or turns on the śruti box. The student sings an elongated "Sā...Pā...Sā (upper octave)...Pā...Sā..." and the class begins. Mayamalava Gowla is traditionally the first raga taught to the student.

With the advance of telecommunications, new ways of teaching Carnatic music have arisen. It is not uncommon now for a student to receive lessons by telephone or even webcam.

Since the late 20th century, there has been some attempts to create Carnatic music grades by music conservatories, which provide standardized tests between different Carnatic teachers. Although such attempts have not met with great popularity in India, standardized exams are often used in countries, like Canada, Great Britain, and France, where there is a high concentration of South Asian expatriates. One of the most widely recognized conservatories of music, is the Toronto-based Thamil Isai Kalaamanram which was formed in 1992. In 2005, it held exams for over 2000 applicants ranging from grades 1 to 7.

The use and disuse of notation

History of notation in Carnatic music

Contrary to what many people think, notation is not a new concept in Indian music. In fact, even the Vedas, although orally transmitted, were written with notation. However, the idea of notation in Carnatic music was not well-received, and it continued to be transmitted orally for centuries. The disadvantage with this system was that if one wanted to learn about a kīrtanam composed, for example, by Purandara Dasa, it involved the formidable task of finding a person from Purandara Dasa's lineage of students.

Written notation of Carnatic music was revived in the late 17th century and early 18th century, which coincided with rule of Shahaji II in Tanjore. Copies of Shahaji's musical manuscripts are still available at the Saraswati Mahal Library in Tanjore and they give us an idea of the music and its form. They contain snippets of solfege to be used when performing the mentioned ragas.

Form of modern notation

Melody

Unlike Western music, Carnatic music is notated almost exclusively in tonic solfa notation using either a Roman or Indic script to represent the solfa names. Past attempts to use the staff notation have mostly failed. Indian music makes use of hundreds of ragas, many more than the church modes in western music. It becomes difficult to write Carnatic music using the staff notation without the use of too many accidentals. Furthermore, the staff notation requires that the song be played in a certain key. The notions of key and absolute pitch are deeply rooted in western music, whereas the carnatic notation does not specify the key and prefers to use scale degrees (relative pitch) to denote notes. The singer is free to choose actual pitch of the tonic note. In the more precise forms of Carnatic notation, there are symbols placed above the notes indicating how the notes should be played or sung; however, informally this practice is not followed.

To show the length of a note, several devices are used. If the duration of note is to be doubled, the letter is either capitalized (if using Roman script) or lengthened by a diacritic (in Indian languages). For a duration of three, the letter is capitalized (or diacriticized) and followed by a comma. For a length of four, the letter is capitalized (or diacriticized) and then followed by a semicolon. In this way any duration can be indicated using a series of semicolons and commas.

However, a simpler notation has evolved which does not use semicolons and capitalization, but rather indicates all extensions of notes using a corresponding number of commas. Thus, Sā quadrupled in length would be denoted as "S,,,".

Rhythm

The notation is divided into columns, depending on the structure of the tāḷaṃ. The division between a laghu and a dhṛtaṃ is indicated by a ।, called a ḍaṇḍā, and so is the division between two dhṛtaṃs or a dhṛtaṃ and an anudhṛtaṃ. The end of a cycle is marked by a ॥, called a double ḍaṇḍā, and looks like a caesura.

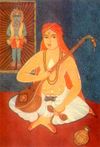

Purandara Dasa

Purandara Dasa

Some Artists

One of the earliest and prominent composers in South India was the saint, and wandering devine singer of yore Purandara Dasa (1480-1564). Purandara Dasa is believed to have composed 475,000 songs in Kannada and was a source of inspiration to the later composers like Tyagaraja. He also invented the tala system of Carnatic music. Owing to his contribution to the Carnatic Music he is referred to as the Father of Carnatic Music or Karnataka Sangeethada Pitamaha.

Syama Sastry

Syama Sastry

The great composers

Thyagaraja (1759?-1847), Muthuswami Dikshitar (1776-1827) and Syama Sastri (1762-1827) are regarded as the trinity of carnatic music. Prominent composers prior to the trinity include Vyasatirtha, Purandaradasa,Kanakadasa. Other prominent singers are Annamacharya,Oottukkadu Venkata Kavi, whose exact lifespan is not known, Swathi Thirunal, Narayana teertha, Mysore Sadashiva Rao, Patnam Subramania Iyer, Poochi Srinivasa Iyengar, Mysore Vasudevacharya, Muthaiah Bhagavathar and Papanasam Sivan,Veena Kuppaiyar,Chembai Vaidhyanatha Bhagavathar ,Irayyimman Thanmpi, Lalgudi Jayaram and Maharajapuram Santhanam.

Modern vocalists

Mangalampalli Balamurali Krishna and DK Pattammal are some of the art's greatest living (albeit aging) performers. M.S. Subbulakshmi, who enthralled audiences across language barriers, is usually credited with popularizing the Carnatic tradition outside South India. She died on December 11, 2004. Legendary singer belonging to the Dhanammal school of music T. Brinda was known for her gamaka laden interpretations of core carnatic ragams and also her vast repertoire. She was awarded the Sangeetha Kalanidhi in 1976. Doyens like Alathur Venkatesa Iyer, Vasanthi Narasimhan, Narayanan Iyengar, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar, Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar and Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer. Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, G.N.Balasubramaniam,. Another great singer who made his own mark with soulful rendering was M D Ramanathan, Contemporary vocalists include Madurai T.N.Seshagopalan, T.V.Sankaranarayanan, Sudha Ragunathan, Sanjay Subrahmanyan, the Priya sisters (Haripriya and Shanmukhapriya), Kiranavali Vidyasankar,Gayathri Girish, Aruna Sairam,Ranjani & Gayatri, R. Vedavalli, Kalpakam Swaminathan, and Bombay Jayashree . Large festivals of Carnatic music always include performances by such people.

To date, there is only one Westerner who became a Carnatic musician of some popularity. His name is Jon B Higgins ("Higgins bhagavatar").

External links

- Raagalaya Foundation. RAAGALAYA is dedicated to the literary development and promotion of classical music, dance and other art forms from India in the US and Europe.

- www.rasikas.org CARNATIC MUSIC FORUMS

- [2]. Site containing streamable carnatic intrumental and vocal songs.

- Carnatic. Offers an insight into Carnatic music and renowned Carnatic composers.

- Sangeetham. Started by the popular and well-known musician Sanjay Subrahmanyan, it is a huge storehouse of information on the musical system and its practitioners. Highlights include a searchable database of compositions (with lyrics and meanings), detailed information of Carnatic music personalities, and a very active discussion forum.

- Carnatic Corner. This was the first comprehensive portal on Carnatic music. It has links to almost all the Carnatic sites in existence as well as a reference library and page of lists for ragas, compositions and lyrics.

- Carnatica. An innovative portal on Carnatic music. It has a great deal of information, and also offers products such as albums, CD-ROMs, VCDs, etc. Its other services include online music courses, camps and so forth.

- Blue Lotus Informatics (Carnatic music CD-ROMs)

- Korvai.org. Started by young mridangist M. N. Hariharan (the author of the book "Korvais Made Easy"), contains information about korvais, notation for percussion lessons, etc.

- carnatic.com - An introduction, lyrics, audio, information on instruments and musicians, and links.

- A Carnatic music primer, from the Carnatic Music Association of North America.

- A Gentle Introduction to South Indian Classical (Karnatic) Music (PDF copy)

- Karnatic, an excellent resource with song lyrics and composer listings.

- Carnatic Potpourri, a variety of information about Carnatic music, features a directory of South India musican -related sites with small description

- vimoksha - Indian classical music and dance portal. An informative site on Carnatic and Hindustani music and various forms of Indian classical dance.

- http://www.carnaticindia.com A complete site on south Indian Classical music and free concert video downloads.

Bibliography

- Carnatic music. In Encyclopædia Britannica (15). (2005).

- Panchapakesa Iyer, A. S. (2003). Gānāmrutha Varna Mālikā. Gānāmrutha Prachuram.

Footnotes

- ↑ The violin of Carnatic music is the same instrument as the violin of Western music, though tuned and held differently. It was introduced to India in the 19th century, when Balusvami Dikshitar (1786–1859), brother of Muttusvami Dikshitar, learnt the violin from a European violinist, and decided to adapt it to the South Indian system of music. It is particularly well suited for Indian music because it can produce the microtones that are essential to the Indian musical tradition. In North India, however, indigenous bowed instruments such as the sārangi continue to be used. The flute was invented independently in India and the West; Krishna is said to have been a master of it. The difference is that the Indian flute is a bamboo tube with open holes, quite unlike the modern western version.

- The vīṇā stalwart, Chitti Babu, was known for his anger and short temper; he is known to have interrupted the concert temporarily or even walked away because the percussionist didn't keep the correct rhythm!

Categories: Classical music

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: