| |

Opera

Music Sound

Opera

List of famous operas | Operas by genre | Arias

Sydney Opera House: one of the world's most recognizable opera

houses and landmarks.

Sydney Opera House: one of the world's most recognizable opera

houses and landmarks.

Opera refers to a

dramatic art form, originating in Europe, in which the emotional content or

primary entertainment is conveyed to the audience as much through music, both

vocal and instrumental, as it is through the lyrics. From the beginning of the

form (about 1600), there has been contention whether the music is paramount, or

the words, a theme that Richard Strauss took up in his final opera, Capriccio

(1942). Also, dramatic speech in opera is often sung in recitative.

By contrast, in

musical theater, dialogue is spoken and an actor's dramatic performance is

generally more important than in opera.

Comparable art forms from various parts of the world, many of them quite

ancient in origin, exist and are also sometimes called "opera" by analogy,

usually prefaced with an adjective indicating the region (for example

Chinese opera). However, other than superficial similarities, these other

art forms developed independently from and are completely unrelated to opera but

are art forms in their own right, not derivatives of opera.

The drama is presented using the primary elements of

theatre such as scenery, costumes, and acting. However, the words of the opera, or

libretto,

are customarily

sung rather than spoken. The

singers are

accompanied by a

musical ensemble ranging from a small instrumental ensemble to a full

symphonic

orchestra.

Besides words and music, opera draws from many other art forms. The visual

arts, such as painting, scenery and sculpture, are employed to create the visual spectacle on the stage; in the

Baroque

"English opera" or

Restoration spectacular, visual arts are especially important, even

predominant. Finally,

dancing is often part of an opera performance, particularly in France.

Generally, however, opera is distinguished from other dramatic forms by the

importance of song.

Singers and the roles they play are initially classified according to their

vocal ranges. Male singers are classified by

vocal

range as bass,

bass-baritone,

baritone,

tenor and

countertenor. Female singers are classified by vocal range as contralto,

mezzo-soprano and

soprano.[1]

Additionally, singers' voices are loosely identified by characteristics other

than range,such as timbre or color, vocal quality, agility, power, and

tessitura. Thus a soprano may be termed a lyric soprano, coloratura, soubrette,

spinto, or dramatic soprano; these terms, although not fully describing a

singing voice, associate the singer's voice with the roles most suitable to the

singer's vocal characteristics. The German Fach system is an

especially organized system of classification. A particular singer's voice may

change drastically over his or her lifetime, rarely reaching vocal maturity

until the third decade, and sometimes not until middle age.

Traditional opera consists of two modes of singing:

recitative,

the dialogue and plot-driving passages often sung in a non-melodic style

characteristic of opera, and

aria, during which

the movement of the plot often pauses, with the music becoming more melodic in

character and the singer focusing on one or more topics or emotional affects.

Short melodic or semi-melodic passages occurring in the midst of what is

otherwise recitative are also referred to as arioso. In the late 19th

century, many composers abolished much of the distinction between recitative and

aria, writing opera that is essentially presented in a restlessly melodic arioso

style throughout. All types of singing in opera are accompanied by

musical instruments, though until the late 17th century generally, and

persisting until even later in some regions, recitative was accompanied by only

the continuo group (harpsichord and 'cello or bassoon). During the period 1680

to roughly 1750, when composers often used both methods of recitative

accompaniment in the same opera, the continuo-only practice was referred to as

"secco" (dry) recitative, while orchestral-accompanied recitative was called

"accompagnato" or "stromentato." The complexity of orchestral accompaniment to

recitative continually tended to become more complex until, in the late 18th

century, composers began to write

recitativo obbligato at dramatic junctures of

opera

seria, in which the orchestra has independent passages of a violent or

pathetic character, sometimes reflecting musical motifs or the melodies of

important arias.

Some genres of opera use spoken dialogue accompanied or unaccompanied by an

orchestra rather than recitative. Such dialogue also is the essential feature of

melodrama,

in its original 19th century sense. Such melodrama grew partly from the practice

that seems to have originated in the 16th century of writing

incidental music to stage plays, either those already existing or newly

composed. The most familiar example of such to most readers will probably be

Mendelssohn's music for A Midsummer Night's Dream; this work is almost certainly the most

frequently performed of the genre in a context separate from its accompanying

play, and has been transcribed for nearly all imaginable chamber combinations,

as well as concert band. The pit orchestra underscoring the dramatic action in

19th century melodrama survives in today's tradition of

film

scores, and spectacular films incorporating serious music can be considered

the direct heirs of melodrama. Perhaps such film scores can in some sense even

be considered both the heirs and the competitors of

grand

opera.

History

Origins

The word opera means "work" in Italian (from the Latin), the plural of

opus suggesting that it combines the arts of solo & choral singing declamation,

and dancing in a staged spectacle. "Dafne" by Jacopo Peri was the earliest

composition considered opera, as understood today. It was written around 1597,

largely under the inspiration of an elite circle of literate Florentine

humanists who gathered as the "Camerata". Significantly Dafne was an attempt to

revive the classical Greek drama, part of the wider revival of antiquity characteristic of the

Renaissance. The members of the Camerata considered that the "chorus" parts

of Greek dramas were originally sung, and possibly even the entire text of all

roles; opera was thus conceived as a way of "restoring" this situation. "Dafne"

is unfortunately lost. A later work by Peri,

Euridice,

dating from 1600, is the first opera score to have survived to the present day.

Peri's works, however, did not arise out of a creative vacuum in the area of

sung drama. An underlying prerequisite for the creation of opera proper was the

practice of monody. Monody is the solo singing/setting of a dramatically

conceived melody, designed to express the emotional content of the text it

carries, which is accompanied by a relatively simple sequence of chords rather

than other polyphonic

parts. Italian composers began composing in this style late in the 16th century,

and it grew in part from the long-standing practise of performing polyphonic

madrigals with one singer accompanied by an instrumental rendition of the

other parts, as well as the rising popularity of more popular, more homophonic

vocal genres such as the

frottola

and the

villanella. In these latter two genres, the increasing tendency was toward a

more homophonic texture, with the top part featuring an elaborate, active

melody, and the lower ones (usually these were three-part compositions, as

opposed to the four-or-more-part madrigal) a less active supporting structure.

From this, it was only a small step to fully-fledged monody. All such works

tended to set humanist poetry of a type that attempted to imitate Petrarch and

his Trecento followers, another element of the period's tendency toward a desire

for restoration of principles it associated with a mixed-up notion of antiquity.

The solo madrigal, frottola, villanella and their kin featured prominently in

semi-dramatic spectacles that were funded in the last seventy years of the 16th

century by the opulent and increasingly secular courts of Italy's city-states.

Such spectacles, called intermedi,

were usually staged to commemorate significant state events; weddings, military

victories, and the like, and alternated in performance with the acts of plays.

Like the later opera, an intermedi featured the aforementioned solo singing, but

also madrigals performed in their typical multi-voice texture, and dancing

accompanied by the present instrumentalists. The intermedi tended not to tell a

story as such, although they occasionally did, but nearly always focused on some

particular element of human emotion or experience, expressed through

mythological allegory.

Another popular court entertainment at this time was the "madrigal drama,"

later also called "madrigal opera" by musicologists familiar with the later

genre. This, as can probably be guessed, consisted of a series of madrigals

strung together to suggest a dramatic narrative.

In addition to opera in Italy, developing concurrently in the late 16th-early

17th centuries were the English

masque and the French ballet au court, which were similar to the Italian intermedi in many

respects. In both cases, the main difference apart from local musical style was

a greater degree of audience (at this time, of course, the audience consisted

only of invited nobles and courtiers) participation in the form of staged or

processional dances. The English masque also featured a culminating "revel," in

which the performers drifted into and cavorted with the audience. Opera was

imported into both countries before the middle of the 17th century, where it

fused with the local incipient genres. This led to the dominance of ballet in

opera of the French tradition, while the thriving English tradition of

incidental music, as well as the totalitarian Cromwell regime at mid-century,

made it difficult for Italian-style opera to take hold there.

In earlier times, music had been part of medieval mystery plays, with the

composer of these best-known to modern audiences being Hildegard of Bingen.

Whether these are to be regarded as possible progenitors of opera is highly

debatable. At the time of their original performance, they were easily regarded

as liturgical accretions. Such accretions to the generally prescribed system of

chants were quite common, and the liturgical ceremony was itself dramatic to a

degree, often featuring elaborate processions, to which the actions associated

with liturgical drama may have been considered merely a minor addition. A new,

17th century form of religious drama, the

oratorio

did arise shortly after the advent of opera, though it owes at least as much to

the (originally secular) non-dramatic recititive-aria form of the

cantata.

Baroque opera

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long; in 1637 the idea

of a "season" (Carnival) of publicly-attended operas supported by ticket sales

emerged in Venice. Influential 17th century opera composers included Francesco

Cavalli and Claudio Monteverdi whose Orfeo (1607) is the earliest opera still

performed today. Monteverdi's later Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (1640) is also

seen as a very important work of early opera. In these early Baroque operas,

broad comedy was blended with tragic elements in a mix that jarred some educated

sensibilities, sparking the first of opera's many reform movements, sponsored by

Venice's Arcadian Academy (not a physical school, but rather a group of

like-minded aristocrats and pedants), but which came to be associated with the

poet Pietro Trapassi, called Metastasio, whose librettos helped crystallize so-called

opera

seria's moralizing tone. Once the Metastasian ideal had been firmly

established, comedy in Baroque-era opera was reserved for what came to be called

opera

buffa. Before such elements were forced out of opera seria, many librettos

had featured a separately unfolding comic plot as sort of an

"opera-within-an-opera." One reason for this was an attempt to attract members

of the growing merchant class, newly wealthy, but still less cultured than the

nobility, to the public opera houses. These separate plots were almost

immediately resurrected in a separately developing tradition that partly derived

from the

commedia dell'arte, (as indeed, such plots had always been) a

long-flourishing improvisitory stage tradition of Italy. Just as intermedi had

once been performed in-between the acts of stage plays, operas in the new comic

genre of "intermezzi", which developed largely in Naples in the 1710s and '20s,

were initially staged during the intermissions of opera seria. They became so

popular, however, that they were soon being offered as separate productions.

Italian opera set the Baroque standard. Italian

libretti were the norm, even when a German composer like Handel found himself writing for London audiences. Italian libretti remained

dominant in the

classical period as well, for example in the operas of

Mozart, who wrote in Vienna near the century's close.

Bel canto and Italian nationalism

The bel

canto opera movement flourished in the early 19th century and is exemplified

by the operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Pacini, Mercadante and many others. Literally "beautiful singing", bel canto

opera derives from the Italian stylistic singing school of the same name. Bel

canto lines are typically florid and intricate, requiring supreme agility and

pitch control.

Following the bel canto era, a more direct, forceful style was rapidly

popularized by Giuseppe Verdi, beginning with his biblical opera Nabucco.

Verdi's writing demanded vocal endurance and strength more than the agility

required in bel canto (although his work includes arias demanding great vocal

agility); his works were also more demanding dramatically, and many listeners

prefer to hear his work sung by voices with great expressive quality, even at

the sacrifice of beautiful tone.[2] Verdi's operas resonated with the growing

spirit of Italian nationalism in the post-Napoleonic

era, and he quickly became an icon of the nationalist movement (although his own

politics were perhaps not quite so radical).

French opera

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French

tradition, sung in the French, was founded by Italian Jean-Baptiste Lully. Lully arrived at court as a dancer and companion for

young Louis XIV, that he might practice his Latin by conversing with a native

speaker. Despite his foreign origin, he established an Academy of Music and

monopolized French opera from 1672; and thus an Italian championed the French

style in the struggle for supremecy between the French and Italian operatic

styles, which raged in the French press for over a century. Lully's overtures,

fluid and disciplined recitatives, danced interludes, divertissements

and orchestral entr'actes between scenes, set a pattern that Gluck

struggled to "reform" almost a century later. The text was as important as the

music: royal propaganda was expressed in elaborate allegories, generally with

affirmatory endings. Opera in France has continued to include

ballet

interludes and feature elaborate scenic machinery.

Baroque French opera, elaborated by

Rameau,[3] was in some sense simplified by the reforms associated with Gluck (Alceste

and Orfee) in the 1760s. Gluck's arias and choruses advanced the plot, a

significant innovation to the static, even irrelevant, arias and choruses common

at the time. The use of choruses at all had been unstylish, especially in Italy,

for almost a century. While the methods of Gluck were partially derived from

those of the more progressive Italians (particularly in comic operas such as

Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona, which had been influential in France since its

performance there in 1752), he also desired to strip opera of some Italian

characteristics he considered superfluous and confusing. In this effort, he

adopted such French tendencies as more syllabic text-setting, use of the chorus

(still occasionally used in France, unlike Italy), and less adherence to the

standard da capo aria form. Because Gluck combined Italian and French methods of

undermining opera seria, his reforms united those styles, his response to an

ever-continuing controversy. Later in the century and early in the first half of

the 19th, French opera was influenced by the

bel canto

style of Rossini

and other Italians. This international synthesis of styles leads directly into

19th century French "Grand Opera," the most grandiose operatic genre of the 19th

century with the possible exception of some Wagner works.

Other "comic" styles

French opera with spoken dialogue is referred to as

opéra comique, regardless of its subject matter — it can include serious and

even tragic plots, such as Bizet's Carmen and Massenet's Manon.

German opera of this type is called

Singspiel.

Depending on the weight of its subject matter, opera comique shades into

operetta,

which arose as a wildly popular form of entertainment in the second half of the

19th century. Along with the music-hall potpourri called

vaudeville, this gave rise to the 20th century genre of musical comedy, perfected in New York and London between the wars.

Romantic opera and French grand opéra

The synthesis of elements that is French

grand

opéra first appeared in

Daniel-François-Esprit Auber's La muette de Portici (1828), Rossini's Guillaume

Tell (1829) and Meyerbeer's Robert le Diable (1831). Grand opera is usually in

four or five acts and includes dance interludes for a complete ballet company.

While this genre reached its apotheosis in Giuseppe Verdi's masterpiece Don

Carlos, the most famous opera in the French grand opera tradition may be

Gounod's Faust, particularly in the United States where it was a favorite at the

Met for the better half of the 20th century. But it should be noted that Faust

started out as an opéra comique, and did not reach grand opera status until

later. By mid-century, opera practically meant Grand Opera; the works of Verdi,

supposedly a quintessential Italian composer, owe much to this genre, as do

those of Wagner, who was both influenced and made acceptable by the sheer

extravagance of scale involved in such productions. The similarly extravagant

production, including ballet set pieces, of such Russian works as Tchaikovsky's

Eugene Onegin can probably be traced back to the grand opera tradition as

well.

German-language opera

Before the late 18th century, German-language opera was largely a copy of the

Italian, although in early-century works of such composers as Reinhard Keiser,

the German-speakers achieved a seriousness of tone and grandeur of scale rarely

approached in Italy. The above-mentioned singspiel also flourished at

this time, being descended from the school dramas with interpolated songs that

the students in Lutheran church-schools often produced.

Mozart's

German

Singspiel Die Zauberflöte (1791) stands at the head of a

German opera tradition that was developed in the 19th century by Beethoven (who

wrote only one, which actually stands more in the French Revolutionary "rescue

opera" tradition of Balfe and Gretry), Heinrich Marschner, Weber (composer of

the great Der Freischütz, containing elements of both singspiel and melodrama,

and a major influence on several Romantic composers) and eventually Wagner.

Before Wagner, there had been little all-sung German language opera of any

account for several decades. Though very much inspired by the works of Weber,

Wagner pioneered a through-composed style, in which recitative and aria blend

into one another and are constantly accompanied by the orchestra; this results

in a sort of endless melody, which is perpetuated by the avoidance of any clear

cadence until moments of great articulation. Wagner also made copious use of the

leitmotif,

a dramatic device which associates a musical line with each character or idea in

the story. Weber had used a similar device earlier, and was hardly the first to

do so; in Wagner's work, however, leitmotifs are a main building-block of his

scores, rather than mere recurring motifs.

Other national operas

Spain also produced its own distinctive form of opera, known as zarzuela, which had two separate flowerings: one in the 17th century, and another

beginning in the mid-19th century. During the 18th century, Italian opera was

immensely popular in Spain, supplanting the native form.

Just as it was in Spain, Italian opera was highly popular in Russia. In the

19th century, Russian composers also began to write important operas based on

nationalist themes, national literature, and folk tales, beginning with

Mikhail Glinka (e.g. Ruslan and Lyudmila) and followed by Alexander Borodin

(Prince Igor), Modest Mussorgsky (Boris Godunov, Khovanshchina), Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov (Sadko), and Pyotr Tchaikovsky (Eugene Onegin). These

developments mirrored the growth of Russian nationalism across the artistic

spectrum, in part as a function of the more general Slavophilism movement.

Czech composers also developed a thriving national opera movement of their

own in the 19th century. Antonín Dvořák, most famous for Rusalka, wrote 13

operas; Bedřich Smetana wrote eight (The Bartered Bride being the most famous);

and Leoš Janáček wrote ten, including Jenůfa, The Cunning Little Vixen, and

Katyá Kabanová.

The key figure of Hungarian national opera in the 19th century was

Ferenc

Erkel, mostly dealing with historical themes. Among his most often performed

operas are Hunyadi László and Bánk bán.

Verismo and after

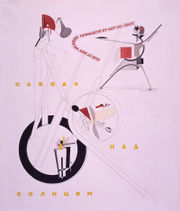

El Lissitzky's poster for the modernist opera Victory over the Sun (1923).

El Lissitzky's poster for the modernist opera Victory over the Sun (1923).

After Wagner, all opera for many decades laboured in his gigantic shadow.

Nearly all composers felt they must react or respond to him in some way, and

opera in the early 20th century took several paths. One fairly short-lived path

was manifested in the sentimental "realistic" melodramas of verismo

operas, a style introduced by Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana, Ruggiero

Leoncavallo's Pagliacci and such popular operas of Giacomo Puccini as La Boheme

and Tosca. Another reaction to Wagner's mythic medievalizing can be seen in the

psychological intensity and social commentary of Richard Strauss (e.g. Salome,

Elektra).

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, opera has enjoyed tremendous appeal

and has been performed around the world. But only a few twentieth-century operas

premičred after the first performance of Puccini's Turandot in 1926 are

regularly performed: Strauss's Arabella and Capriccio, Berg's Lulu, Stravinsky's

The Rake's Progress, Britten's Peter Grimes and Billy Budd and Poulenc's

Dialogues of the Carmelites are among these.

Sociology of opera

All art forms have a social context, and opera likewise cannot exist in a

vacuum. A string quartet exists in manuscript and printed score, and a truly

musical person, playing one part, or seated at a keyboard, can hear the intent

of the music, but the printed score for an opera must be realized in a

production, even a slender one, for its impact. Thus there exists a "sociology

of opera", which would be as interesting to general social historians (who are

unaware of it, on the whole) as it is to opera buffs. Operas have always been

written with a specific audience in mind, whether more aristocratic or more

popular, expressing their local prejudices and expectations, and even taking

account of the vocal character of certain singers' voices. Operas have also been

affected behind the scenes, by

opera

house politics and sometimes government

censors. But, the idea that there is a canon of operas, an opera repertory which

is reflected in a "List of famous operas," for example, is a late entry in the sociology of opera.

Indeed, for most of opera's history, only new works were acceptable to

audiences; an opera house that mounted productions of twenty year-old operas (or

certainly any older) would with but few exceptions have been equivalent to a

modern movie house showing similarly outdated films.

Development of the idea of "opera repertory"

During the lifetimes of composers up to Meyerbeer there was no "repertory" of

operas. Composers like Bellini and Donizetti were expected to come up with fresh

material, season after season, even if they had to cannibalize their own works

for material that had not been offered to that city's audience (compare

pastiche). One common strategy was to imitate the work of other composers,

especially when such work had achieved considerable success. The idea of an

opera repertory originated with Richard Wagner, in his Festspielhaus in

Bayreuth.

The

list of famous operas is a good guide to the standard operatic repertory

reflected in contemporary productions and recordings.

Media

Notes

- ^ Men sometimes sing in

the "female" vocal ranges, in which case they are termed sopranist,

countertenor, and contralto. Of these, only the countertenor is commonly

encountered in opera, sometimes singing parts written for castrati

-- men neutered at a young age specifically to give them a higher singing

range.

- ^ An outstanding example

of this would be

Maria Callas. Her voice was unarguably flawed, but she possessed enormous

acting talent and a wide range of vocal coloration. Oddly, she was able to

apply this quality to great effect in tragic operas from the bel canto

period, such as Lucia di Lammermoor and Norma.

- ^ Rameau was actually

opposed by many French critics of his own day for altering Lully's practises;

others, on the other hand, saw him as a champion of French sensibilities

against the rising popularity of Italian opera in the country.

See also

The foyer of Charles Garnier's Opéra, Paris, opened 1875.

The foyer of Charles Garnier's Opéra, Paris, opened 1875.

General references

- The

New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie (1992), 5,448

pages, is the best, and by far the largest, general reference in the English

language.

ISBN 0-333-73432-7 and ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- The Viking Opera Guide (1994), 1,328 pages,

ISBN 0-670812927

- The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, by John Warrack and Ewan West

(1992), 782 pages,

ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- Opera, the Rough Guide, by Matthew Boyden et al. (1997), 672

pages,

ISBN 1-85828-138-5

Further reading

- Andersen, H. C., Opera and Evil Kings (ISBN

0-325-25779-7)

-

DiGaetani, John Louis, An Invitation to the Opera (ISBN

0-385-26339-2)

- Simon, Henry W. (1946). A Treasury of Grand Opera. Simon and

Schuster, New York, NY.

External links

Home | Up | List of musical forms | Ballet | Concertos | Dances | Gendhing | Opera | Operetta | Sonatas | Song forms | Aleatoric music | Arch form | Bagatelle | Ballad | Ballade | Ballet | Bar form | Barcarolle | Binary form

Music Sound, v. 2.0, by MultiMedia

This guide is licensed under the GNU

Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia.

|

|