Tea is a beverage made by steeping processed leaves, buds or twigs of the tea bush Camellia sinensis in hot water for a few minutes. The processing can include oxidation (fermentation), heating, drying and the addition of other herbs, flowers, spices and fruits.

There are four types of true tea: black tea, oolong tea, green tea, and white tea. The term herbal tea usually refers to infusions of fruit or herbs such as rosehip tea, chamomile tea and Jiaogulan that contain no tea leaves. (Alternative terms for herbal tea that avoid the word "tea" are tisane and herbal infusion). This article is concerned exclusively with preparations and uses of the tea plant Camellia sinensis.

Tea is a natural source of caffeine, theophylline, theanine, and antioxidants, but it has almost no fat, carbohydrates, or protein. It has a cooling, slightly bitter and astringent taste.

Contents |

Processing and classification

The types of tea are distinguished by their processing. Leaves of Camellia sinensis, if not dried quickly after picking, soon begin to wilt and oxidize. This process resembles the malting of barley, in that starch is converted into sugars; the leaves turn progressively darker, as chlorophyll breaks down and tannins are released. The next step in processing is to stop the oxidation process at a predetermined stage by taking the water from the leaves via heating.

The term fermentation was used (probably by wine fanciers) to describe this process, and has stuck, even though no true fermentation happens (i.e., the process is not driven by yeast and produces no ethanol). Without careful moisture and temperature control, however, fungi will grow on tea. The fungi cause real fermentation which will contaminate the tea with toxic and carcinogenic substances, so that the tea must be discarded.

Tea is traditionally classified based on the degree or period of fermentation (oxidation) the leaves have undergone:

- White tea

- Young leaves (new growth buds) that have undergone no oxidation; the buds may be shielded from sunlight to prevent formation of chlorophyll. White tea is produced in lesser quantities than most of the other styles, and can be correspondingly more expensive than tea from the same plant processed by other methods. It is also less well-known in countries outside of China, though this is changing with increased western interest in organic or premium teas.

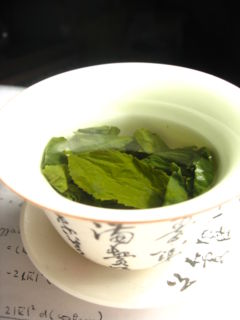

- Green tea

- The oxidation process is stopped after a minimal amount of oxidation by application of heat; either with steam, a traditional Japanese method; or by dry cooking in hot pans, the traditional Chinese method. Tea leaves may be left to dry as separate leaves are rolled into small pellets to make gun-powder tea. The latter process is time-consuming and is typically done only with pekoes of higher quality. The tea is processed within one to two days of harvesting.

- Oolong

- Oxidation is stopped somewhere between the standards for green tea and black tea. The oxidation process will take two to three days.

- Black tea/Red tea

- The tea leaves are allowed to completely oxidize. Black tea is the most common form of tea in southern Asia (India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan etc) and in the last century many African countries including Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda, Malawi and Zimbabwe. The literal translation of the Chinese word is red tea, which may be used by some tea-lovers. The Chinese call it red tea because the actual tea liquid is red. Westerners call it black tea because the tea leaves used to brew it are usually black. However, red tea may also refer to rooibos, an increasingly popular South African tisane. The oxidation process will take around two weeks and up to one month. Black tea is further classified as either orthodox or CTC (Crush, Tear, Curl, a production method developed about 1932). Unblended black teas are also identified by the estate they come from, their year and the flush (first, second or autumn). Orthodox and CTC teas are further graded according to the post-production leaf quality by the Orange Pekoe system.

- Pu-erh

- (also known as Póu léi (Polee) in Cantonese), Two forms of pu-erh teas are available, "raw" and "ripened". "Raw" or "green" pu-erh may be consumed young or aged to further mature. During the aging process, the tea undergoes a second, microbial fermentation. "Ripened" pu-erh is made from green pu-erh leaf that has been artificially oxidized to approximate the flavour of the natural aging process. This is done through a controlled process similar to composting, where both the moisture and temperature of the tea are carefully monitored. Both types of pu-erh tea are usually compressed into various shapes including bricks, discs, bowls, or mushrooms. While most teas are consumed within a year of production, pu-erh can be aged for many years to improve its flavour, up to 30 to 50 years for raw pu-erh and 10 to 15 years for ripened pu-erh, although experts and aficionados disagree about what the optimal age is to stop the aging process. Most often, pu-erh is steeped for up to five minutes in boiling water. Additionally, some Tibetans use pu-erh as a caloric food, boiled with yak butter, sugar and salt to make yak butter tea. Teas that undergo a second oxidation, such as pu-erh and liu bao, are collectively referred to as black tea in Chinese. This is not to be confused with the English term Black tea, which is known in Chinese as red tea.

- Yellow tea

- Either used as a name of high-quality tea served at the Imperial court, or of special tea processed similarly to green tea, but with a slower drying phase.

- Kukicha

- Also called winter tea, kukicha is made from twigs and old leaves pruned from the tea plant during its dormant season and dry-roasted over a fire. It is popular as a health food in Japan and in macrobiotic diets.

- Genmaicha

- Literally "brown rice tea" in Japanese, a green tea blended with dry-roasted brown rice (sometimes including popped rice), very popular in Japan but also drunk in China.

- Flower tea

- Teas processed or brewed with flowers; typically, each flower goes with a specific category of tea, such as green or red tea. The most famous flower tea is jasmine tea (hua chá, literally "flower tea," in Mandarin; heung pín in Cantonese), a green or oolong tea scented (or brewed) with jasmine flowers. Chrysanthemum, osmanthus, lotus, rose, and lychee are also popular flowers.

Da Hong Pao tea an

Oolong tea

|

Fuding

Bai Hao Yinzhen tea, a white tea

|

Green

Pu-erh tuo cha, a type of compressed raw

pu-erh

|

Huoshan Huangya tea a Yellow tea

|

Blending and additives

Almost all teas in bags and most other teas sold in England are blends. Blending may occur at the level of tea-planting area (e.g., Assam), or teas from many areas may be blended. The aim of blending is a stable taste over different years, and a better price. More expensive, better tasting tea may cover the inferior taste of cheaper tea.

There are various teas which have additives and/or different processing than "pure" varieties. Tea is able to easily receive any aroma, which may cause problems in processing, transportation or storage of tea, but can be also advantageously used to prepare scented teas.

Content

Tea contains catechins, a type of antioxidant. In fresh tea leaf, catechins can be up to 30% of the dry weight. Catechins are highest in concentration in white and green teas while black tea has substantially less due to its oxidative preparation. Tea also contains the stimulants caffeine (about 3% of the dry weight and typically 40 mg per cup of prepared tea), theophylline and theobromine, the latter two being present in very small amounts.[1]

Origin and early history in Asia

The cradle of the tea plant is a region that encompasses eastern and southern China, northern Myanmar, and the Assam state of India. Spontaneous (wild) growth of the assamica variant is observed in area ranging from Chinese province Yunnan to the northern part of Myanmar and Assam region of India. The variant sinensis grows naturally in eastern and southeastern regions of China.[2] Recent studies and occurrence of hybrids of the two types in wider area extending over mentioned regions suggest the place of origin of tea is in an area consisting of the northern part of Myanmar and the Yunnan and Sichuan provinces of China.[3]

Origins of human use of tea are described in several myths, but it is unknown as to where tea was first created as a drink.

Creation myths

In one popular Chinese legend, Shennong, the legendary Emperor of China, inventor of agriculture and Chinese medicine, was on a journey about five thousand years ago. The Emperor, known for his wisdom in the ways of science, believed that the safest way to drink water was by first boiling it. One day he noticed some leaves had fallen into his boiling water. The ever inquisitive and curious monarch took a sip of the brew and was pleasantly surprised by its flavour and its restorative properties. Variant of the legend tells that the emperor tried medical properties of various herbs on himself, some of them poisonous, and found tea works as an antidote.[4] Shennong is also mentioned in Lu Yu's Cha Jing, famous early work on the subject.[5]

A Chinese legend, which spread along with Buddhism, Bodhidharma is credited with discovery of tea. Bodhidharma, a semi-legendary Buddhist monk, founder of the Chan school of Buddhism, journeyed to China. He became angered because he was falling asleep during meditation, so he cut off his eyelids. Tea bushes sprung from the spot where his eyelids hit the ground.[6] Sometimes, the second story is retold with Gautama Buddha in place of Bodhidharma[7] In another variant of the first mentioned myth, Gautama Buddha discovered tea when some leaves had fallen into boiling water.[8]

China

Whether or not these legends have any basis in fact, tea has played a significant role in Asian culture for centuries as a staple beverage, a curative, and a symbol of status. It is not surprising its discovery is ascribed to religious or royal origins. The fact is that the Chinese have enjoyed tea for centuries. Scholars hailed the brew as a cure for a variety of ailments, the nobility considered the consumption of good tea as a mark of their status and the common people simply enjoyed its flavour.

While historically the origin of tea as a medicinal herb useful for staying awake is unclear, China is considered the birthplace of tea drinking with recorded tea use in its history to at least 1000 BC. The Han Dynasty used tea as medicine. The use of tea as a beverage drunk for pleasure on social occasions dates from the Tang Dynasty or earlier.

The Tang Dynasty writer Lu Yu's 陸羽 (729-804) Cha Jing 茶經 is an early work on the subject. According to Cha Jing written around 760, tea drinking was widespread. The book describes how tea plants were grown, the leaves processed, and tea prepared as a beverage. It also describes how tea was evaluated. The book even discusses where the best tea leaves were produced.

At this time in tea's history, the nature of the beverage and style of tea preparation were quite different from the way we experience tea today. Tea leaves were processed into cakes. The dried teacake, generally called brick tea was ground in a stone mortar. Hot water was added to the powdered teacake, or the powdered teacake was boiled in earthenware kettles then consumed as a hot beverage.

A form of compressed tea referred to as white tea was being produced as far back as the Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.). This special white tea of Tang was picked in early spring when the new growths of tea bushes that resemble silver needles were abundant. These "first flushes" were used as the raw material to make the compressed tea.

Advent of steaming and powder tea

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), production and preparation of all tea changed. The tea of Song included many loose-leaf styles (to preserve the delicate character favoured by the court society), but a new powdered form of tea emerged. Tea leaves were picked and quickly steamed to preserve their colour and fresh character. After steaming, the leaves were dried. The finished tea was then ground into fine powders that were whisked in wide bowls. The resulting beverage was highly regarded for its deep emerald or iridescent white appearance and its rejuvenating and healthy energy. Drinking tea was considered stylish among government officers and intellectuals during the Southern Song period in China (12th to 13th centuries). They would read poetry, write calligraphy, paint, and discuss philosophy, while enjoying tea. Sometimes they would hold tea competitions where teas and tea instruments were judged. When Song Dynasty emperor Hui Zhong proclaimed white tea to be the culmination of all that is elegant, he set in motion the evolution of an enchanting variety.

This Song style of tea preparation incorporated powdered tea and ceramic ware in a ceremonial aesthetic known as the Song tea ceremony. Japanese monks traveling to China at this time had learned the Song preparation and brought it home with them. Although it later became extinct in China, this Song style of tea evolved into the Japanese tea ceremony, which endures today.

Many forms of white tea were made in the Song Dynasty due to the discerning tastes of the court society. Hui Zhong, who ruled China from 1101-1125, referred to white tea as the best type of tea, and he has been credited with the development of many white teas in the Song Dynasty, including "Palace Jade Sprout" and "Silver Silk Water Sprout".

Producing white teas was extremely labour-intensive. First, tea was picked from selected varietals of cultivated bushes or wild tea trees in early spring. The tea was immediately steamed, and the buds were then selected and stripped of their outer, unopened leaf. Only the delicate interior of the bud was reserved to be rinsed with spring water and dried. This process produced white teas that were paper thin and small.

Once processed, the finished tea was distributed and often given as a tribute to the Song court in loose form. It was then ground to a fine, silvery-white powder that was whisked in the wide ceramic bowls used in the Song tea ceremony. These white powder teas were also used in the famous whisked tea competitions of that era.

Roasting and brewing

Steaming tea leaves was the primary process used for centuries in the preparation of tea. After the transition from compressed tea to the powdered form, the production of tea for trade and distribution changed once again. The Chinese learned to process tea in a different way in the mid-13th century. Tea leaves were roasted and then crumbled rather than steamed. This is the origin of today's loose teas and the practice of brewed tea.

In 1391, the Ming court issued a decree that only loose tea would be accepted as a "tribute". As a result, loose tea production increased and processing techniques advanced. Soon, most tea was distributed in full-leaf, loose form and steeped in earthenware vessels.

Oxidization (often mistakenly called fermentation)

Tea "fermentation" is not related to yeast fermentation. It is actually the oxidization of the tea leaves. In 17th century China numerous advances were made in tea production. In the southern part of China, tea leaves were sun dried then half fermented, producing Black Dragon teas or Oolongs. However, this method was not common in the rest of China.

Korea

The first historical record documenting the offering of tea to an ancestral god describes a rite in the year 661 in which a tea offering was made to the spirit of King Suro, the founder of the Geumgwan Gaya Kingdom (42-562).

Records from the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) show that tea offerings were made in Buddhist temples to the spirits of revered monks.

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the royal Yi family and the aristocracy used tea for simple rites, the "Day Tea Rite" was a common daytime ceremony, whereas the "Special Tea Rite" was reserved for specific occasions. These terms are not found in other countries. Toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, commoners joined the trend and used tea for ancestral rites, following the Chinese example based on Zhu Xi's text formalities of Family.

Stoneware was common, ceramic more frequent, mostly made in provincial kilns, with porcelain rare, imperial porcelain with dragons the rarest.

Historically the appearance of the bowls and cups is naturalistic, with a division according to religious influence. Celadon or jade green, "punchong", or bronze-like weathered patinas for Buddhist tea rituals; the purest of white with faint designs in porcelain for Confucian tea rituals; and coarser porcelains and ash-stone glazes for animist tea rituals, or for export to Japan where they were known as "gohan chawan". An aesthetic of rough surface texture from a clay and sand mix with a thin glazing were particularly prized and copied. The randomness of this creation was said to provide a "now moment of reality" treasured by tea masters.

Unlike the Chinese tradition, no Korean tea vessels used in the ceremony are tested for a fine musical note. Judgment instead is based on naturalness in form, emotion, and colouring.

The earliest kinds of tea used in tea ceremonies were heavily pressed cakes of black tea, the equivalent of aged pu-erh tea still popular in China. Vintages of tea were respected, and tea of great age imported from China had a certain popularity at court. However, importation of tea plants by Buddhist monks brought a more delicate series of teas into Korea, and the tea ceremony.

While green tea, "chaksol" or "chugno", is most often served, other teas such as "Byeoksoryung" Chunhachoon, Woojeon, Jakseol, Jookro, Okcheon, as well as native chrysanthemum tea, persimmon leaf tea, or mugwort tea may be served at different times of the year.

Buddhist monks incorporated tea ceremonies into votive offerings. However the Goryeo nobility and later the Confucian yangban scholars formalized the rituals. Tea ceremonies have always been used for important occasions such as birthdays, anniversaries, remembrance of old friends, and increasingly a way to rediscovering Seon meditation.

Japanese Involvement

Importing tea and tea culture

The earliest known references to green tea in Japan are in a text written by a Buddhist monk in the 9th century. Tea became a drink of the religious classes in Japan when Japanese priests and envoys sent to China to learn about its culture brought tea to Japan. The first form of tea brought from China was probably in a teacake. Ancient recordings indicate the first batch of tea seeds were brought by a priest named Saicho (最澄; 767-822) in 805 and then by another named Kukai (空海; 774-835) in 806. It became a drink of the royal classes when Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇), the Japanese emperor, encouraged the growth of tea plants. Seeds were imported from China, and cultivation in Japan began.

Kissa Yojoki - the Book of Tea

In 1191, the famous Zen priest Eisai (栄西; 1141-1215) brought back tea seeds to Kyoto. Some of the tea seeds were given to the priest Myoe Shonin, and became the basis for Uji tea. The oldest tea specialty book in Japan, Kissa Yojoki (喫茶養生記; how to stay healthy by drinking tea) was written by Eisai. The two-volume book was written in 1211 after his second and last visit to China. The first sentence states, "Tea is the ultimate mental and medical remedy and has the ability to make one's life more full and complete". The preface describes how drinking tea can have a positive effect on the five vital organs, especially the heart. It discusses tea's medicinal qualities which include easing the effects of alcohol, acting as a stimulant, curing blotchiness, quenching thirst, eliminating indigestion, curing beriberi, preventing fatigue, and improving urinary and brain function. Part One also explains the shapes of tea plants, tea flowers and tea leaves and covers how to grow tea plants and process tea leaves. In Part Two, the book discusses the specific dosage and method required for individual physical ailments.

Eisai was also instrumental in introducing tea consumption to the warrior class, which rose to political prominence after the Heian Period. Eisai learned that the shogun Minamoto no Sanetomo had a habit of drinking too much every night. In 1214, Eisai presented a book he had written to the general, lauding the health benefits of tea drinking. After that, the custom of tea drinking became popular among the Samurai.

Very soon, green tea became a staple among cultured people in Japan -- a brew for the gentry and the Buddhist priesthood alike. Production grew and tea became increasingly accessible, though still a privilege enjoyed mostly by the upper classes.

Roasting process introduced to Japan

In the 13th century Ming dynasty, southern China and Japan enjoyed much cultural exchange. Significant merchandise was traded and the roasting method of processing tea became common in Kyushu, Japan. Since the steaming (9th century) and the roasting (13th century) method were brought to Japan during two different periods, these teas are completely distinct from each another.

Japan tea culture emerges

The pastime made popular in China in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries -- reading poetry, writing calligraphy, painting, and discussing philosophy while enjoying tea – eventually became popular in Japan and with Samurai society. The modern tea ceremony developed over several centuries by Zen Buddhist monks under the original guidance of the monk Sen-no Rikyu (1522-1591). In fact, both the beverage and the ceremony surrounding it played a prominent role in feudal diplomacy. Many of the most important negotiations among feudal clan leaders were carried out in the austere and serene setting of the tea ceremony. By the end of the sixteenth century, the current "Way of Tea" was established. Eventually, green tea became available to the masses, making it the nation's most popular beverage.

Modern Japanese green tea

In 1738, Soen Nagatani developed Japanese sencha (Japanese: 煎茶), which is an unfermented form of green tea. To prepare sencha, tea leaves are first steam-pressed, then rolled and dried into a loose tea.

In 1835, Kahei Yamamoto developed gyokuro (Japanese: 玉露), considered the finest loose-leaf Japanese green tea, by shading tea trees during the weeks leading up to harvesting in order to alter the leaf chemistry in ways considered pleasant by most green tea drinkers.

Modern maccha (Japanese: 抹茶) is normally taken from the same shaded trees as gyokuro and ground to a fine powder to be mixed whole into hot water, and is the tea used in the Japanese tea ceremony.

Rolling machines

At the end of the Meiji period (1868-1912), machine manufacturing of green tea was introduced and began replacing handmade tea. Machines took over the processes of primary drying, tea rolling, secondary drying, final rolling, and steaming.

Automation

Automation contributed to improved quality control and reduced labour. Sensor and computer controls were introduced to machine automation so that unskilled workers can produce superior tea without compromising in quality. Certain regions in Japan are known for special types of green tea, as well as for teas of exceptional quality, making the leaves themselves a highly valued commodity. This combination of Nature's bounty and manmade technical breakthroughs combine to produce the most exceptional green tea products sold on the market today. Today, roasted green tea is not as common in Japan and powdered tea is used in ceremonial fashion.

Tea spreads to the world

As the Venetian explorer Marco Polo failed to mention tea in his travel records, it is conjectured that the first Europeans to encounter tea were either Jesuits living in Beijing who attended the court of the last Ming Emperors; or Portuguese explorers visiting Japan in 1560. Russia discovered tea in 1618 after a Ming Emperor of China offered it as a gift to Czar Michael I.

Soon imported tea was introduced to Europe, where it quickly became popular among the wealthy in France and the Netherlands. English use of tea dates from about 1650 and is attributed to Catherine of Braganza (Portuguese princess and queen consort of Charles II of England).

The high demand for tea in Britain caused a huge trade deficit with China, leading the British to try to produce their own in the mid-nineteenth century. Using seeds smuggled from China (there was an official ban on foreigners entering tea-growing areas), the British went through some failed experiments but finally succeeded in setting up productive plantations in parts of colonial India with suitable climates and soil.[9][10] They also tried to balance the trade deficit by selling opium to the Chinese, which later led to the First Opium War in 1838–1842.

The Boston Tea Party was an act of uprising in which Boston residents destroyed crates of British tea in 1773, in protest against British tea and taxation policy. Prior to the Boston Tea Party, residents of Britain's North American 13 colonies drank far more tea than coffee. In Britain, coffee was more popular. After the protests against the various taxes, British Colonists stopped drinking tea as an act of patriotism. Similarly, Britons slowed their consumption of coffee.

Iced Tea has been popular in North America since the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair.

These days, contradicting tea economies do exist. Tea farmers in Japan, Taiwan and China often enjoy better incomes compared to farmers in black tea producing countries.

The word tea

The Chinese character for tea is 茶, but it is pronounced differently in the various Chinese dialects. Two pronunciations have made their way into other languages around the world. One is 'te' (Taiwanese (linguistics): tê) which comes from the Min Nan dialect spoken around the port of Xiamen (Amoy). The other is Chá, used by the Cantonese dialect spoken around the ports of Guangzhou (Canton), Hong Kong, Macau, and in overseas Chinese communities, as well as in the Mandarin dialect of northern China. Yet another different pronunciation is 'zu', used in the Wu dialect spoken around Shanghai.

Languages that have Te derivatives include Afrikaans (tee), Armenian, Catalan (te), Czech (té or thé, but these words sound archaic, čaj is used nowadays, see the next paragraph), Danish (te), Dutch (thee), English (tea), Esperanto (teo), Estonian (tee), Faroese (te), Finnish (tee), French (thé), (West) Frisian (tee), Galician (té), German (Tee), Hebrew (תה, /te/ or /tei/), Hungarian (tea), Icelandic (te), Indonesian (teh), Irish (tae), Italian (tè), scientific Latin (thea), Latvian (tēja), Malay (teh), Norwegian (te), Polish (herbata from Latin herba thea), Scots Gaelic (tì, teatha), Singhalese, Spanish (té), Swedish (te), Tamil (thè), Welsh (te), and Yiddish (טיי, /tei/).

Those that use Cha or Chai derivatives include Albanian (çaj), Arabic (شَاي/shi/chai), Assyrian (pronounced chai), Azeri: (çay), Bengali (চা), Bosnian (čaj), Bulgarian (чай), Capampangan (cha), Cebuano (tsa), Croatian (čaj), Czech (čaj), Greek (τσάι), Hindi (चाय)chai, Japanese (茶, ちゃ, cha), Kazakh (шай), Korean (차), Macedonian (čaj), Malayalam, Nepali (chai), Persian (چاى), Punjabi (ਚਾਹ), Portuguese (chá), Romanian (ceai), Russian, (чай, chai), Serbian (чај), Slovak (čaj), Slovene (čaj), Somali (shaax), Swahili (chai), Tagalog (tsaa), Thai (ชา), Tibetan (ja), Turkish (çay), Ukrainian (чай), Urdu (چاى), Uzbek (choy) and Vietnamese (trà and chè are both direct derivatives of the Chinese 茶; the latter term is used mainly in the north).

The Polish word for a tea-kettle is czajnik, which could be derived directly from Cha or from the cognate Russian word. However, tea in Polish is herbata, which was probably derived from the Latin herba thea, meaning "tea herb".

It is tempting to correlate these names with the route that was used to deliver tea to these cultures, although the relation is far from simple at times. As an example, the first tea to reach Britain was traded by the Dutch from Fujian, which uses te, and although later most British trade went through Canton, which uses cha, the Fujianese pronunciation continued to be the more popular.

In Ireland, or at least in Dublin, the term "cha" is sometimes used for tea, with "tay" as a common pronunciation throughout the land (derived from the Irish Gaelic tae), and "char" was a common slang term for tea throughout British Empire and Commonwealth military forces in the 19th and 20th centuries, crossing over into civilian usage. In North America, the word "chai" is used to refer almost exclusively to the Indian "chai" (or "masala chai") beverage.

Perhaps the only place in which a word unrelated to tea is used to describe the beverage is South America (particularly Andean countries), because a similar stimulant beverage, hierba mate, was consumed there long before tea arrived. In various places of South America, any tea is referred to as mate.

Tea culture

Tea is often drunk at social events, such as afternoon tea and the tea party. It may be drunk early in the day to heighten alertness; it contains theophylline and bound caffeine (sometimes called "theine"), although there are also decaffeinated teas.

There are tea ceremonies which have arisen in different cultures, Japan's complex, formal and serene one being the most known. Other examples are the Korean tea ceremony or some traditional ways of brewing tea in Chinese tea culture.

Preparation

This section describes the most widespread method of making tea. Completely different methods are used in North Africa, Tibet and perhaps in other places. In the American South, iced tea is also prepared differently.

The best way to prepare tea is usually thought to be with loose tea placed either directly in a teapot or contained in a tea infuser, rather than a teabag. However, perfectly acceptable tea can be made with teabags. Some circumvent the teapot stage altogether and brew the tea directly in a cup or mug. This method is becoming more popular. For an acceptable quality, however, it is necessary to obey the rules for preparation such as sufficient infusion time by placing the teabag in the cup before pouring the hot water.

Historically in China, tea is divided into a number of infusions. The first infusion is immediately poured out to wash the tea, and then the second and further infusions are had. The third through fifth are nearly always considered the best infusions of tea, although different teas open up differently and may require more infusions of boiling water to bring them to life.

Typically, the best temperature for brewing tea can be determined by its type. Teas that have little or no oxidation period, such as a green or white tea, are best brewed at lower temperatures around 80 °C, while teas with longer oxidation periods should be brewed at higher temperatures around 100 °C.

- Black tea

- The water for black teas should be added at the boiling point (100 °C or 212 °F), except for more delicate teas, where lower temperatures are recommended. This will have as large an effect on the final flavour as the type of tea used. The most common fault when making black tea is to use water at too low a temperature. Since boiling point drops with increasing altitude, this makes it difficult to brew black tea properly in mountainous areas. It is also recommended that the teapot be warmed before preparing tea, easily done by adding a small amount of boiling water to the pot, swirling briefly, before discarding. Black tea should not be allowed to steep for less than 30 seconds or more than about five minutes (a process known as brewing or [dialectally] mashing in the UK). After that, tannin is released, which counteracts the stimulating effect of the theophylline and caffeine and makes the tea bitter (at this point it is referred to as being stewed in the UK). Therefore, for a "wake-up" tea, one should not let the tea steep for more than 2- 3minutes. When the tea has brewed long enough to suit the tastes of the drinker, it should be strained while serving.

- Green tea

- Water for green tea, according to most accounts, should be around 80 °C to 85 °C (176 °F to 185 °F); the higher the quality of the leaves, the lower the temperature. Hotter water will burn green-tea leaves, producing a bitter taste. Preferably, the container in which the tea is steeped, the mug, or teapot should also be warmed beforehand so that the tea does not immediately cool down.

- Oolong tea

- Oolong teas should be brewed around 90 °C to 100 °C (194 °F to 212 °F), and again the brewing vessel should be warmed before pouring in the water. Yixing purple clay teapots are the ideal brewing vessel for oolong tea. For best results use spring water, as the minerals in spring water tend to bring out more flavour in the tea.

- Premium or delicate tea

- Some teas, especially green teas and delicate Oolong or Darjeeling teas, are steeped for shorter periods, sometimes less than 30 seconds. Using a tea strainer separates the leaves from the water at the end of the brewing time if a tea bag is not being used.

- Serving

- In order to preserve the pre-tannin tea without requiring it all to be poured into cups, a second teapot is employed. The steeping pot is best unglazed earthenware; Yixing pots are the best known of these, famed for the high quality clay from which they are made. The serving pot is generally porcelain, which retains the heat better. Larger teapots are a post-19th-century invention, as tea before this time was very rare and very expensive. Experienced tea-drinkers often insist that the tea should not be stirred around while it is steeping (sometimes called winding in the UK). This, they say, will do little to strengthen the tea, but is likely to bring the tannic acids out in the same way that brewing too long will do. For the same reason one should not squeeze the last drops out of a teabag; if stronger tea is desired, more tea leaves should be used.

- Additives

- The addition of other items such as

milk and sugar to tea is primarily a European

invention[11], though it has also spread to british

colonies such as Hong Kong[12] or India. Some

connoisseurs eschew cream because it overpowers the flavour of tea. Many

teas are traditionally drunk with milk. These include

Indian

chai, and British tea blends. These teas tend to be

very hearty varieties which can be tasted through the

milk, such as Assams, or the East Friesian blend. Milk

is thought to neutralise remaining tannins and reduce

acidity.

Sugar cubes ready to be added to a cup of tea

Sugar cubes ready to be added to a cup of tea - When taking milk with tea, some add the tea to the milk rather than the other way around when using chilled milk; this avoids scalding the milk, leading to a better emulsion and nicer taste.[13] The socially 'correct' order is tea, sugar, milk, but this convention was established before the invention of the refrigerator. It is worth noting that this convention was only universally established in the 20th century - prior to this, the common earthenware mugs used were unable to withstand the temperature of the tea, and so the convention was to add the tea to the milk. This was not the case with bone china.

- Adding the milk first also makes a milkier cup of tea with sugar harder to dissolve as there will be no hot liquid in the cup. In addition, the amount of milk used is normally determined by the colour of the tea, therefore milk is added until the correct colour is obtained. If the milk is added first, more guesswork is involved. If the tea is being brewed in a mug, the milk is generally added after the tea bag is removed (however, it is arguably better to add milk before removing the tea bag than it is to remove the tea bag too soon: the tea will continue to brew even with milk added).

- Other popular additives to tea include sugar or honey, lemon, and fruit jams.

- In colder regions such as Mongolia and Nepal, butter is added to provide necessary calories. Tibetan butter tea contains rock salt and yak butter, which is then churned vigorously in a cylindrical vessel closely resembing a butter churn. The flavour of this beverage is more akin to a rich broth than to tea, and may be described as a very acquired taste to those unused to drinking it.

- Ceremony

- Zen Buddhism is the root of the highly refined Japanese tea ceremony. The Chinese province of Fujian is the origin of the Gong Fu tea ceremony, which is unrelated to the martial art called Kung Fu though the characters are the same: literally "time-energy" or something which takes a lot of time and energy. It features the rapid use of tongs and various vessels to make tea. Loose leaf tea venders in China often use this method to make tea for their customers. The Korean Tea Ceremony is more like the Chinese ceremony.

- In the United Kingdom, adding the milk first is historically considered a lower-class method of preparing tea; the upper classes always add the milk last. The origin of this distinction is said to be that the rougher earthenware mugs of the working class would break if boiling-hot tea was added directly to them, whereas the fine glazed china cups of the upper class would not. It is now considered by most to be a personal preference.

Packaging

- Tea bags

- Tea leaves are packed into a small (usually paper) tea bag. It is easy and convenient, making tea bags popular for many people nowadays. However, because fannings and dust from modern tea processing are also included in most tea bags, it is commonly held among tea aficionados that this method provides an inferior taste and experience. The paper used for the bag can also be tasted by many which can detract from the tea's flavour.

- Additional reasons why bag tea is considered less well-flavoured include:

-

- Dried tea loses its flavour quickly on exposure to air. Most bag teas (although not all) contain leaves broken into small pieces; the great surface-area-to-volume ratio of the leaves in tea bags exposes them to more air, and therefore causes them to go stale faster. Loose tea leaves are likely to be in larger pieces, or to be entirely intact.

- Breaking up the leaves for bags extracts flavoured oils.

- The small size of the bag does not allow leaves to diffuse and steep properly.

- Triangle Tea Bags

- A new infuser has recently come onto the market with an unusual design. The mesh triangle bags are made of a gossamer mesh and have been criticized of being environmentally unfriendly. The shape is designed to allow the tea leaves to expand more when steeping, and not leave flavours (such as paper) in the tea, addressing two of connoisseurs' arguments against tea bags. As such, the flavours available tend towards more gourmet selections such as white tea rather than blends.

- Loose tea

- The tea leaves are packaged loosely in a canister or other container. The portions must be individually measured by the consumer for use in a cup, mug or teapot. This allows greater flexibility, letting the consumer brew weaker or stronger tea as desired, but convenience is sacrificed. Strainers, "tea presses", filtered teapots and infusion bags are available commercially to avoid having to drink the floating loose leaves. A more traditional, yet perhaps more effective way around this problem is to use a three-piece lidded teacup, called a gaiwan. The lid of the gaiwan can be tilted to decant the leaves while pouring the tea into a different cup for consumption.

- Compressed tea

- A lot of tea is still compressed for storage and aging convenience. Commonly Pu-Erh tea is compressed and then drunk by loosening leaves off using a small knife. Most of the time compressed tea can be stored longer than loose leaf tea.

- Tea sticks

- One of the more modern forms of tea consumption, an alternative to the tea bag, is tea sticks.

- The first known tea sticks originated in Holland in the mid 1990's, where a company by the name of Venezia Trading produced a tea stick named Ticolino. Ticolino are dubbed as single serving tea sticks which use an infusing technology to brew the tea leaves inside, releasing the flavour and aroma.

- Instant tea

- In recent times, "instant teas" are becoming popular, similar to freeze dried instant coffee. Instant tea was developed in the 1930's, but not commercialized until the late 1950's, and is only more recently becoming popular. These products often come with added flavours, such as vanilla, honey or fruit, and may also contain powdered milk. Similar products also exist for instant iced tea, due to the convenience of not requiring boiling water. Tea connoisseurs tend to criticise these products for sacrificing the delicacies of tea flavour in exchange for convenience.

Storage

Tea storage is essential to keeping the taste of tea pure. Tea absorbs moisture and odours very easily so it is necessary to keep it in some kind of container away from strong odours. One way to store a small amount of loose leaf tea is to keep it in a tin or glass container. These containers will keep the tea free from moisture and also keep odours out so the tea will keep its original flavour. Other ways to store tea include air tight bags. When storing the tea keep it away from sun light, strong odours, and moisture. For larger amounts of tea it would be good to put it into a cooler type of container. First wrap the tea in brown paper then wrap the paper again with brown paper to keep out any moisture. Then place the tea into a cooler that has nothing in and has a good seal. Next take the tea to a cool place away from moisture and odours. The length of time you can store tea depends on its type. Some teas such as flower teas will go bad in a month or so, but others may get better with age.

References

- ^ Graham H. N.; Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry; Preventive Medicine 21(3):334-50 (1992).

- ^ Yamamoto p. 2

- ^ Yamamoto p. 4

- ^ Chow p. 19-20 (Czech edition); also Arcimovicova p. 9, Evans p. 2 and others

- ^ Lu Ju p. 29-30 (Czech edition)

- ^ Chow p. 20-21

- ^ Evans p. 3

- ^ Okakura

- ^ Tea in History. thesimpleleaf.com.

- ^ History of Darjeeling. Darjeeing Research and Development Center.

- ^ The History of Tea. Stash Tea (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-07.

- ^ Hong Kong Style Milk Tea. ibiblio, Richard R. Wertz (1998). Retrieved on 2006-11-07.

- ^ How to make a perfect cuppa. BBC News (2003-06-25). Retrieved on 2006-07-28.

- Jana Arcimovičová, Pavel Valíček (1998): Vůně čaje, Start Benešov. ISBN 80-902005-9-1 (in Czech)

- T. Yamamoto, M Kim, L R Juneja (editors): Chemistry and Applications of Green Tea, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-4006-3

- Lu Yu (陆羽): Cha Jing (茶经) (The classical book on tea). References are to Czech translation of modern-day editon (1987) by Olga Lomová (translator): Kniha o čaji. Spolek milců čaje, Praha, 2002. (in Czech)

- John C. Evans (1992): Tea in China: The History of China's National Drink,Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28049-5

- Alastair G.Power (1988) 'Tea's Made', 'Under the Influence: Of Tea' ISBN 0-8443-2986-3

- Kit Chow, Ione Kramer (1990): All the Tea in China, China Books & Periodicals Inc. ISBN 0-8351-2194-1 References are to Czech translation by Michal Synek (1998): Všechny čaje Číny, DharmaGaia Praha. ISBN 80-85905-48-5

- Stephan Reimertz (1998): Vom Genuß des Tees : Eine eine heitere Reise durch alte Landschaften, ehrwürdige Traditionen und moderne Verhältnisse, inklusive einer kleinen Teeschule (In German)

- Jane Pettigrew (2002), A Social History of Tea

- Roy Moxham (2003), Tea: Addiction, Exploitation, and Empire

External links

General

Online books

- Tea Leaves, Francis Leggett & Co., 1900, from Project Gutenberg

- The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura from Project Gutenberg and a PDF version (2.8 MB) typeset in TeX

- The Little Tea Book, by Arthur Gray, 1903, from Project Gutenberg

Tea history, culture and local specifics

- Turkish Tea

- The Industrial Revolution and Tea-drinking

- Taiwanese Tea Culture

- Russian Tea How to describes the Russian method for making tea and elaborates on the surrounding culture and equipment (notably samovar)

- British Standard 6008:1980 (aka ISO 3103:1980) Method for preparation of a liquor of tea for use in sensory tests.

- George Orwell: A Nice Cup of Tea An essay by author George Orwell describing his own methods of making tea.

- How to make a perfect cup of tea News Release from Royal Society of Chemistry

- A humorous article on making tea

- Map of Tearooms in the United States

- 10 part series on the history of iced tea

- Tea infos from italy offers the addresses of tea shops and tea rooms in italy, large bibliography and FAQ.

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: