| |

Whale song

Music Sound

Whale song

Humpback whales are well known for their songs

Humpback whales are well known for their songsWhale song is the

sounds made by whales to communicate. The word "song"

is used in particular to describe the pattern of regular and predictable sounds

made by some species of whales (notably the humpback) in a way that is

reminiscent of human singing.

The mechanisms used to produce sound vary from one family of

cetaceans to another. Marine mammals, such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises,

are much more dependent on sound for communication and sensation than land

mammals are , as other senses are of limited effectiveness in water. Sight is

limited for marine mammals because of the way water absorbs light. Smell is also

limited, as molecules diffuse more slowly in water than air, which makes

smelling less effective. In addition, the speed of sound in water is roughly

four times that in the atmosphere at sea level. Because sea-mammals are so

dependent on hearing to communicate and feed, environmentalists and cetologists

are concerned that they are being harmed by the increased ambient noise in the

world's oceans caused by ships and marine seismic surveys.

Production of sound

Humans produce sound by expelling air through the larynx. The vocal cords

within the larynx open and close as necessary to separate the stream of air into

discrete pockets of air. These pockets are shaped by the throat, tongue, and

lips into the desired

sound.

Cetacean sound production differs markedly from this mechanism. The precise

mechanism differs in the two major sub-families of cetaceans: the Odontoceti (toothed

whales—including dolphins) and the Mystceti (baleen whales—including the largest

whales, such as the Blue Whale).

Toothed whale sound production

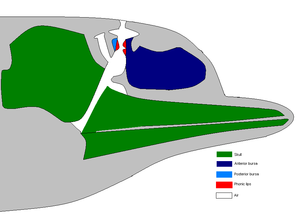

Idealized dolphin head showing the regions involved in sound production. This

image was redrawn from Cranford (2000).

Idealized dolphin head showing the regions involved in sound production. This

image was redrawn from Cranford (2000).

Toothed whales do not make the long, low-frequency sounds known as the whale

song. Instead they produce rapid bursts of high-frequency clicks and whistles.

Single clicks are generally used for

echolocation whereas collections of clicks and whistles are used for

communication. Though a large pod of dolphins will make a veritable cacophony of

different noises, very little is known about the meaning of the sound. Frankell

(1998) quotes one researcher characterizing listening to such a school as like

listening to a group of children at a playground.

The multiple sounds themselves are produced by passing air through a

structure in the head rather like the human nasal passage called the phonic

lips. As the air passes through this narrow passage, the phonic lip membranes

are sucked together, causing the surrounding tissue to vibrate. These vibrations

can, as with the vibrations in the human larynx, be consciously controlled with

great sensitivity. The vibrations pass through the tissue of the head to the

melon, which shapes and directs the sound into a beam of sound for echolocation.

Every toothed whale except the sperm whale has two sets of phonic lips and is

thus capable of making two sounds independently. Once the air has passed the

phonic lips it enters the vestibular sac. From there the air may be recycled back into the lower part

of the nasal complex, ready to be used for sound creation again, or passed out

through the blowhole.

The

French name for phonic lips—museau de singe—translates to "monkey lips," which

the phonic lip structure is supposed to resemble. New cranial analysis using

computed axial and single photon emission computed tomography scans in 2004

showed that, at least in the case of bottlenose dolphins, air may be supplied to

the nasal complex from the lungs by the palatopharyngeal sphincter, enabling the sound creation process to continue

for as long as the dolphin is able to hold their breath (Houser et al., 2004).

Baleen whale sound production

Baleen whales do not have phonic lip structure. Instead they have a larynx

that appears to play a role in sound production, but it lacks vocal chords and

scientists remain uncertain as to the exact mechanism. The process, however,

cannot be completely analogous to humans because whales do not have to exhale in

order to produce sound. It is likely that they recycle air around the body for

this purpose. Cranial sinuses may also be used to create the sounds, but again

researchers are currently unclear how.

Purpose of whale-created sounds

While the complex and haunting sounds of the Humpback Whale (and some Blue

Whales) are believed to be primarily used in

sexual selection (see section below), the simpler sounds of other whales have a

year-round use. While toothed dolphins (including the Orca) are capable of using

echolocation (essentially the emission of ultra-sonic beams of sound waves) to

detect the size and nature of objects very precisely, baleen whales do not have

this capability. Further, unlike some fish such as sharks, a whale's

sense of smell is not highly developed. Thus given the poor visibility of

aquatic environments and the fact that sound travels so well in water,

human-audible sounds play a role in such whales' navigation. For instance, the

depth of water or the existence of a large obstruction ahead may be detected by

loud noises made by baleen whales.

The song of the Humpback Whale

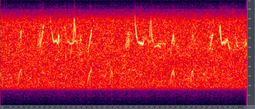

Humpback Whale song spectrogram,

Humpback Whale song spectrogram,

Two groups of whales, the Humpback Whale and the subspecies of Blue Whale

found in the

Indian

Ocean, are known to produce the repetitious sounds at varying frequencies

known as whale song. Marine biologist Philip Clapham describes the song as

"probably the most complex [songs] in the animal kingdom" (Clapham, 1996).

Male Humpback Whales perform these vocalizations only during the mating

season, and so it is surmised the purpose of songs is to aid sexual selection.

Whether the songs are a competitive behavior between males seeking the same

mate, a means of defining territory or a "flirting" behavior from a male to a

female is not known and the subject of on-going research. Males have been

observed singing while simultaneously acting as an "escort" whale in the

immediate vicinity of a female. Singing has also been recorded in competitive

groups of whales that are composed of one female and multiple males.

Interest in whale song was aroused by researchers Roger Payne and Scott McVay,

who analysed the songs in 1971. The songs follow a distinct hierarchical

structure. The base units of the song (sometimes loosely called the "notes")

are single uninterrupted emissions of sound that last up to a few seconds. These

sounds vary in frequency from 20 Hz to 10 kHz (the typical human range of

hearing is 20 Hz to 20 kHz). The units may be frequency modulated (i.e., the

pitch of the sound may go up, down, or stay the same during the note) or

amplitude modulated (get louder or quieter). However the adjustment of bandwidth

on a spectrogram representation of the song reveals the essentially pulsed nature of the FM sounds.

A collection of four or six units is known as a sub-phrase, lasting perhaps

ten seconds (see also phrase (music)). A collection of two sub-phrases is a

phrase. A whale will typically repeat the same phrase over and over for two to

four minutes. This is known as a theme. A collection of themes is known as a

song. The whale will repeat the same song, which last up to 30 or so minutes,

over and over again over the course of hours or even days. This "Russian doll" hierarchy of sounds has captured the imagination of scientists.

All the whales in an area sing virtually the same song at any point in time

and the song is constantly and slowly evolving over time. For example, over the

course of a month a particular unit that started as an "upsweep" (increasing in

frequency) may slowly flatten to become a constant note. Another unit may get

steadily louder. The pace of evolution of a whale's song also changes—some years

the song may change quite rapidly, whereas in other years little variation may

be recorded.

Idealized schematic of the song of a Humpback Whale.

Idealized schematic of the song of a Humpback Whale.

Redrawn from Payne, et al. (1983)

Whales occupying the same geographical areas (which can be as large as entire

ocean basins) tend to sing similar songs, with only slight variations. Whales

from non-overlapping regions sing entirely different songs.

As the song evolves it appears that old patterns are not revisited. An

analysis of 19 years of whale songs found that while general patterns in song

could be spotted, the same combinations never recurred.

Humpback Whales may also make stand-alone sounds that do not form part of a

song, particularly during courtship rituals. Finally, Humpbacks make a third

class of sound called the feeding call. This is a long sound (5 to 10 s

duration) of near constant frequency. Humpbacks generally feed co-operatively by

gathering in groups, swimming underneath shoals of fish and all lunging up

vertically through the fish and out of the water together. Prior to these

lunges, whales make their feeding call. The exact purpose of the call is not

known, but research suggests that fish do know what it means. When the sound was

played back to them, a group of herring responded to the sound by moving away

from the call, even though no whale was present.

Some scientists have proposed that humpback whale song may serve an

echolocative purpose, such as Mercado & Frazer (2001), but has been subject to disagreement (e.g. Au,

Frankel, Helweg, & Cato, 2001).

Other whale sounds

Most baleen whales make sounds at about 15–20

hertz. However, marine biologists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

reported in the New Scientist in December 2004 that they had been tracking a whale in the

North Pacific for 12 years that was "singing" at 52 Hz. The scientists are

currently unable to explain this dramatic difference from the norm; however,

they are sure the whale is a baleen and extremely unlikely to be a new species,

suggesting that currently known species may have a wider vocal range than

previously thought.

Most other whales and dolphins produce sounds of varying degrees of

complexity. Of particular interest is the

Beluga (the

"sea canary") which produces an immense variety of whistles, clicks and pulses.

Human interaction

Though some observers suggest that undue fascination has been placed on the

whales' songs simply because the animals are under the sea, most marine mammal

scientists believe that sound plays a particularly vital role in the development

and well-being of cetaceans. It may be argued those against whaling have

anthropomorphized the behaviour in an attempt to bolster their case. Conversely

pro-whaling nations are perhaps disposed to downplay the meaning of the sounds,

noting for example that little account is taken of the "moo" of cattle.

Researchers use hydrophones (often adapted from their original military use

in tracking submarines) to ascertain the exact location of the origin of whale

noises. Their methods allow them also to detect how far through an ocean a sound

travels. Research by Dr Christopher Clark of Cornell University conducted using thirty years worth of military data

showed that whale noises travel up to 3,000 km. As well as providing information

about song production, the data allows researchers to follow the migratory path

of whales throughout the "singing" (mating) season.

Prior to the introduction of human noise production, Clark says the noises

may have travelled right from one side of an ocean to the other. His research

indicates that ambient noise from boats is doubling each decade. This has the

effect of halving the range of whale noises. Those who believe that whale songs

are significant to the continued well-being of whale populations are

particularly concerned by this increase in ambient noise. Other research has

shown that increased boat traffic in, for example, the waters off Vancouver, has

caused some Orca to change the frequency and increase the amplitude of their

sounds, in an apparent attempt to make themselves heard. Environmentalists fear that such boat activity is putting undue stress on

the animals as well as making it difficult to find a mate.

Whale song in fiction

The song of Humpback Whales was a significant plot element of the film Star

Trek IV: The Voyage Home. The purpose of whale song was the main plot device in

the book Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings by Christopher Moore.

Whale song is also a factor in the worldview of uplifted dolphins in David

Brin's Uplift and Uplift Storm trilogies, comprising elements of religion,

philosophy, cosmology and poetry.

Media

Voyager Golden Records carried whale songs into outer space with other sounds representing planet Earth.

Voyager Golden Records carried whale songs into outer space with other sounds representing planet Earth.

References

- Lone whale's song remains a mystery, New Scientist, issue

number 2477, 11th December 2004

- Sound production, by Adam S. Frankel, in the Encyclopedia of

Marine Mammals (pp 1126-1137)

ISBN 0125513402 (1998)

- Helweg, D.A., Frankel, A.S., Mobley Jr, J.R. and

Herman, L.M., “Humpback whale song: our current understanding,” in

Marine Mammal Sensory Systems, J. A. Thomas, R. A. Kastelein, and A. Y.

Supin, Eds. New York: Plenum, 1992, pp. 459–483.

- In search of impulse sound sources in odontocetes by Ted Cranford

in Hearing by whales and dolphins (W. Lu, A. Popper and R. Fays

eds.). Springer-Verlag (2000).

- Progressive changes in the songs of humpback whales (Megaptera

novaeangliae): a detailed analysis of two seasons in Hawaii by

K.B.Payne, P. Tyack and R.S. Payne in Communication and behavior of

whales. Westview Press (1983)

- "Unweaving

the song of whales", BBC News, 28th February 2005.

- Phil Clapham (1996).

Humpback whales. Colin Baxter Photography.

ISBN 0948661879.

- Dorian S. Houser, James Finneran, Don

Carder, William Van Bonn, Cynthia Smith, Carl Hoh, Robert Mattrey and Sam

Ridgway (2004). "Structural and functional imaging of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops

truncatus) cranial anatomy". Journal of Experimental Biology

207: 3657-3665.

- W. W. L. Au, A. Frankel, D. A. Helweg,

and D. H. Cato (2001). "Against the humpback whale sonar hypothesis".

IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 26: 295–300.

- Frazer, L.N. and Mercado. E. III.

(2000). "A sonar model for humpback whale song". IEEE Journal of Oceanic

Engineering 25: 160–182.

- Mercado, E. III, and Frazer, L.N.

(2001).

"Humpback whale song or humpback whale sonar? A Reply to Au et al.".

IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 26: 406-415.

External links

Home | Up | Songwriter | Christmas music | Commercium song | Cover version | Drinking song | Eurovision Song Contest | Song forms | Songs by genre | Hymn | Instrumental | Musical theatre | Power ballad | Royal anthem | Singles | Songs popular at sporting events | Theme music | Traditional songs | Animal song | Answer song | Bird song | Border ballad | Broadside | Children's song | Earworm | Field holler | Jingle | Lied | Milonga | Modinha | Playground song | Spiritual | Suicide song | Summer hit | Three-chord song | Topical song | Whale song

Music Sound, v. 2.0, by MultiMedia

This guide is licensed under the GNU

Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia.

|

|