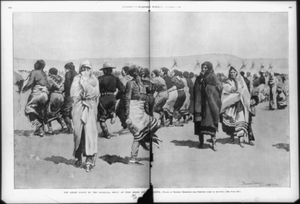

The Ghost Dance by the Ogalala Lakota at Pine

Ridge. Illustration by

Frederic Remington

The Ghost Dance by the Ogalala Lakota at Pine

Ridge. Illustration by

Frederic Remington

Noted in historical accounts as the Ghost Dance of 1890, the Ghost Dance was a religious movement incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. The traditional ritual used in the Ghost Dance, the circle dance, has been used by many Native Americans since pre-historic times, but was first performed in accordance with Jack Wilson's teachings among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs often creating change in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself. At the core of the movement was the prophet of peace Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute, who prophesized a nonviolent end to Euro-American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation. Perhaps the best known facet of the Ghost Dance movement is the role it reportedly played in instigating the Wounded Knee massacre in 1890 that killed 391 Lakota Sioux.[1] The Ghost Dance is most vividly remembered for this Sioux sect, which displayed extensive distortion toward millenarianism, thus driving it away from the religion’s core principles.

Contents |

Historical foundations

Paiute background

Paiutes living in Mason Valley, at the time of settlement by Euro-American homesteaders, are collectively known as the Tövusi-dökadö, “Cyperus-bulb Eaters.” The Northern Paiute community thrived upon a subsistence pattern of foraging through this locally plentiful food source for a portion of the year; while also augmenting their diets with fish, pine nuts, and the occasional clubbing of wild game.

The Tövusi-dökadö lacked any permanent political organization or officials, instead operating within a less stratified social system of self-proclaimed spiritually blessed individuals organizing events or activities for the betterment of the group as a whole. Usually, a community event organized was centered on the observance of a ritual at a prescribed time of year or was intended to organize activities like harvests or hunting parties. One such extraordinary instance illustrating this system occurred in 1869 when a Paiute named Hawthorne Wodziwob organized a series of community dances as a way to announce his vision. He told the Paiutes that he had traveled to the land of the dead, and about the promises that the souls of the recently deceased made to him there. They promised to return to their loved ones within a period of 3-4 years. Wodziwob’s peers accepted this vision, probably due to his already reputable status as a healer, as he also urged the populace to dance the common circle dance as was customary during a time of festival. He continued preaching this message for 3 years with the help of an admiring local weather doctor named Tavibo, Jack Wilson’s father.[2]

Previous to Wodziwob’s religious movement, a devastating typhoid epidemic struck in 1867, coupled with other European diseases one tenth of the population was killed.[3] Not taking into consideration the excessive individual psychological stress this event placed on community members, it more importantly caused grave disorder in the economic system by preventing many families from being able to continue their nomadic lifestyle following pine nut harvests and wild game herds. Without any other options, most of these partial families ended up in Virginia City seeking wage work.

Round dance precursors

The physical form of the ritual associated with Ghost Dance can neither be claimed to have originated from Jack Wilson, or to have died with him. Referred to as the round dance, it characteristically includes a circular community dance held around an individual that leads the ceremony. Often accompanying the ritual are intermissions of trance, exhortations, and prophesying.

The term “prophet dances” was applied during an investigation of Native American rituals carried out by anthropologist Leslie Spier, a student of Franz Boas. He discovered that types of round dances were present throughout much of the Pacific Northwest including the Columbia plateau (including Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of western Montana). However Spier’s study was conducted at a time when most of these rituals had already incorporated Christian elements, further clouding the issue of the round dance’s origin.

Difficultly in acquiring absolute pristine data concerning North America societies during its pre-historic or proto-historic eras has presented itself due to Europeans impact on native populations long before they ever physically reached more remote areas of the continent. Changes in Native American society before physical contact can be attributed to severe disease epidemics, an increased frequency and volume in trade caused by the introduction of European goods or from Europeans purchasing local resources, and the introduction of the horse which revolutionized the foraging lifestyle for some aboriginal societies.

Enculturation and diffusion (anthropology) are not the only explanations for the common circle dance rituals. Anthropologist James Mooney was one of the first to study circle dances and observed striking similarities in rituals between tribes. However he also claimed that “a hope and longing common to all humanity, manifests through behavior rooted in human physiology and common experience”; therefore alluding to either the notion of universal imprints on the human mind, or a ubiquitous behavior drawn from universal life course events.

Jack Wilson's vision

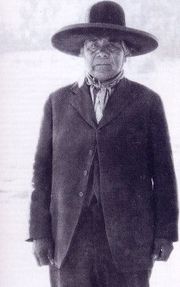

Wovoka –

Paiute spiritual leader and creator of the

Ghost Dance

Wovoka –

Paiute spiritual leader and creator of the

Ghost Dance

Jack Wilson, the prophet formerly known as Wovoka until his adoption of a Euro-American name, experienced a vision on 1889 January 1. Received during a solar eclipse, it was not his first time experiencing a vision directly from God, but now as a young adult he was better spiritually equipped to handle his profound message. Jack had received training from an experienced shaman in his community under his parent’s guidance after realizing that he was having difficulty interpreting his first vision. Jack was also training to be a weather doctor, following in his father’s footsteps, and had established himself throughout Mason Valley as a gifted and blessed young leader. He often presided over circle dances symbolizing the sun’s heavenly path across the sky while his captive audience listened to his preaching of universal love.

Anthropologist James Mooney conducted an interview with the charismatic messiah in 1892. Stories and beliefs that Jack talked about with him were later validated as the same preachings given to his fellow Native Americans.[4] This has been documented by letters between tribes and by notes that Jack asked his pilgrims to take upon their arrival at Mason Valley. Jack told Mooney that when in heaven he was before God, amongst of his ancestors who were engaged in their favorite pastimes. The land was filled with wild game and God showed it to him before instructing him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God continued that Jack’s people must work, not steal or lie; and that they must not engage in the old practices of war. God said that if his people abide by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in this other world. With God, he proclaimed, there will be no sickness, disease, or old age. Jack continues that he was then given a dance and commanded to bring it back to his people. If his people performed this dance, which lasted for five days, in the proper intervals the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. Lastly, God gave Jack powers over weather and told him that he would be the deputy in charge of affairs in the Western United States leaving current President Harrison as God’s deputy in the East. Jack was then told to return home and preach God’s message.

Jack Wilson left the presence of God convinced that if every Indian in the West danced the new dance to “hasten the event”, all evil in the world would be swept away leaving a renewed earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethen, the new religion was termed “dance in a circle”. Although the first time Euro-Americans encountered the practice it was through contact with the Sioux, their expression “spirit dance” was used which was translated into ghost dance.

Role in Wounded Knee Massacre

Through a parade of Native Americans and some Euro-Americans, Jack Wilson’s message spread across much of the western portion of the United States. Early in the religious movement many tribes sent members to investigate the self-proclaimed messiah, other communities sent delegates only to be cordial. Regardless of why people were coming to visit Jack, many left believers and returned to their homeland preaching his message. The Ghost Dance was even incorporated by many Mormons who, residing in Utah, traveled to Jack to evaluate whether or not he was the messiah that Joseph Smith Jr predicted would arrive in the year 1890.[5]

Miniconjou Chief Big Foot lies dead in the snow

Miniconjou Chief Big Foot lies dead in the snow

While most followers of the Ghost Dance understood the messiah as a teacher of pacifism and peace, others, whom the ideals eluded, did not.

A representation of the Ghost Dance’s misinterpretation is the image of the Ghost Shirt, a special garment rumored to repel bullets through spiritual power. While it is uncertain where the belief originated, James Mooney pointed out that the most likely source is the Mormon endowment robe, which members of the Mormon Church believed would protect the pious wearer from danger. Despite the uncertainty of who created the belief, it is certain that chief Kicking Bear brought the concept to his own people, the Lakota Sioux in 1890.[6] Another Lakota interpretation of Jack’s religion, that strays from his core concept, is drawn from the original idea of a “renewed earth” in which “all evil is washed away”. The Lakota understanding of this included the removal of all Euro-Americans from their lands. The same cannot be said of Jack’s order of the Ghost Dance which would teach accepting Euro-Americans.

In 1890 February, the United States government broke a Lakota treaty by adjusting the Great Sioux Reservation of South Dakota, an area that formally encompassed the majority of the state, into five relatively smaller reservations.[7] This was done to accommodate homesteaders from the east and was in accordance with the government’s clearly stated “policy of breaking up tribal relationships” and “conforming Indians to the white man’s ways, peaceably if they will, or forcibly if they must.”[8] Once on the half-sized reservations, tribes were separated into family units on 320 acre plots, forced to farm, raise livestock, and send their children to boarding schools that forbid any inclusion of Native American traditional culture and language.

To help support the Sioux during the period of transition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), was delegated the responsibility of supplementing the Sioux with food and hiring Euro-American farmers as teachers to the once proud hunters. By the end of the 1890 growing season, the Sioux farmer’s hard work trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota failed due to the inability of the land to produce agricultural yields during a time of intense heat and lack of rain. Unfortunately for them, this was also the time when the government’s patience supporting the “lazy” Indians also failed resulting in rations to the Sioux being cut in half. With the bison virtually eradicated from the plains a few years earlier, the Sioux had no option but to starve. Increased performances of the Ghost Dance ritual ensued frightening the supervising agents of the BIA, who successfully requested thousands more troops deployed to the reservation.

By 1890 December 15 a leader of the Hunkpapa Sioux named Sitting Bull was arrested on the reservation for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance. [9]During the incident, a Sioux witnessing the arrest fired at one of the soldiers resulting in an immediate retaliation. Deaths on both sides resulted included the loss of Sitting Bull himself.

Another Sioux leader, Big Foot, was stopped while in route to convene with the remaining Sioux chiefs. U.S. Army officers forced him and his people to relocate to a small camp close to the Pine Ridge Agency in order for the soldiers to be able to more closely watch the old chief who was on the U.S. Army’s list of troublemaking Indians. That evening, December 28th, the small band of Sioux erected their tipis on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek. The following day during an attempt to collect any remaining weapons from the band, one young Sioux warrior refused to relinquish his arms resulting in a struggle in which his weapon discharged into the air. Other young Sioux warrior, protected by their ghost shirts, responded by brandishing their previously concealed weapons to which the U.S. forces responded with carbine firearms. Two bands of Native American reinforcements arrived at the creek, Oglalas and Brules, after hearing the gunshots. After the fighting had concluded 39 U.S. soldiers lay dead amongst the 153 dead Sioux, 62 of which were women and children.[10]

Following the massacre, chief Kicking Bear official surrendered his weapon to General Nelson A. Miles. Outrage in the Eastern United States emerged as the general population learned about the events that had transpired. Many Americans felt U.S. Army actions were harsh and the related the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek to an ungentlemanly act of kicking a man when he is already down. Americans had been told on numerous occasions that the Native American had already been successfully pacified. Public uproar played a role in the reinstatement of the previous treaty’s terms including full rations and more monetary compensation for lands taken away.

Anthropological perspectives

Religious revitalization model

Anthropologist Anthony F. C. Wallace’s model (1956) describing the process of religious revitalization. It is derived from studies of another Native American religious movement, The Code of Handsome Lake, which led to the formation of the Longhouse Religion. [11]

I. Period of generally satisfactory adaptation to a group’s social and natural environment.

II. Period of increased individual stress. While the group as a whole is able to survive through its accustomed cultural behavior, however changes in the social or natural environment frustrate efforts of many people to obtain normal satisfactions of their needs.

III. Period of cultural distortion. Changes on the group’s social or natural environment drastically reduce the capacity of accustomed cultural behavior to satisfy most persons’ physical and emotional needs.

IV. Period of revitalization: (1) reformulation of the cultural pattern, (2) its communication, (3) organization of a reformulated cultural pattern, (4) adaptation of the reformulated pattern to better meet the needs and preferences of the group, (5) cultural transformation, (6) routinization- the adapted reformulated cultural pattern becomes the standard cultural behavior for the group.

V. New period of generally satisfactory adaptation to the group's changed social and/or natural environment.

Ghost Dance within revitalization model

In Alice Beck Kehoe’s ethnohistory of the Ghost Dance, she presents the movement within the framework of Wallace’s model of religious revitalization. The Tövusi-dökadö’s age of traditional subsistence patterns constitutes a period of generally satisfactory cultural adaptation to their environment which lasted until around 1860. Corresponding with an influx of Euro-American settlers begins the second phase of Wallace’s model hallmarked by increased individual stress placed on some members of the community. Almost the entire 1880s are placed into the model’s third period, that of cultural distortion, due to the increased presence of Euro-American agribusiness and the United States’ government. With the introduction of Jack Wilson’s Ghost Dance, the fourth period of revitalization is ushered which characteristically occurs after sufficient changes accrue to significantly warp the society’s cultural pattern. Following the revitalization is yet another period of satisfactory adaptation which is dated to about 1900. By this time almost all sources of traditional food were eradicated from the Tövusi-dökadö’s long-established homeland, leading to the adoption of Euro-American subsistence methods while still maintaining a Paiute culture.

Reason for rejection

“Worthless words” was the description given to the Ghost Dance in 1890 by Navajo leaders.[12] Three years later James Mooney arrived at the Navajo reservation in northern Arizona during his study of the Ghost Dance movement, only realize that the ritual was never incorporated into Navajo society even during the brief period of its widespread acceptance in western portions of the United States. Kehoe describes why the movement never gained fervor in 1890, according to the revitalization model, among the Navajo and illuminates the circumstances of the Navajo’s later acceptance of the Peyote Religion.

Movements with similarities

1856-1857 Cattle-Killing in South Africa in which perhaps 60,000 of the Xhosa people died of self-induced starvation. They destroyed their food supplies based on a vision that came to Nongqawuse.

The Righteous Harmony Society was a Chinese movement which also believed in magical clothing, reacting against Western colonialism.

The Maji Maji Rebellion where an African spirit medium gave his followers war medicine that he said would turn German bullets into water.

The Melanesian Jon Frum cargo cult believed in a return of their ancestors brought by Western technology (see Vailala Madness).

The Spanish Carlist troops fought against secularism and believed in the detente bala — pieces of cloth with an image of the Holy Heart of Jesus — would protect them against bullets.

Burkhanism was an Altayan movement that reacted against Russification.

Child soldiers in the civil wars of Liberia wore wigs and wedding gowns to confuse enemy bullets by assuming a dual identity. (see http://slate.msn.com/id/2086490/)

References

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Massacre at Wounded KneeCreek, pg 24. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Death of Renewal?, pg 32-33. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Death of Renewal?, pg 33. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Mooney, James The Ghost Dance Religion and Wounded Knee. New York: Dover Publications Inc; 1896

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, The Ghost Dance Religion, pg 5. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Massacre at Wounded KneeCreek, pg 13. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Massacre at Wounded KneeCreek, pg 15. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Milligan, Edward A. Dakota Twilight, pg121. Hicksville, NY: Exposition Press; 1896

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Massacre at Wounded KneeCreek, pg 20. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Wallace, Anthony F. C. Revitalization Movements: Some Theoretical Considerations for Their Comparative Study. American Anthropologist n.s. 58(2):264-81. 1956

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Massacre at Wounded KneeCreek, pg 24. Thompson publishing; 1989

- ↑ *Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, Deprivation and the Ghost Dance, pg 103. Thompson publishing; 1989

Further reading

- Kehoe, B Alice The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization Thompson publishing; 1989

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books; 1970

- Du Bois, Cora. The 1870 Ghost Dance. University of California Press; Berkeley, 1939.

- Osterreich, Shelley Anne. The American Indian Ghost Dance, 1870 and 1890. Greenwood Press; New York, 1991.

External links

- Wovoka (Jack Wilson)

- Speech by Kicking Bear

Categories: American Indian music

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: