The classic Hammond electronic organ, invented in the 1930s

and popular for decades thereafter. The Hammond brought an

unprecedented degree of musical capacity into the home, far

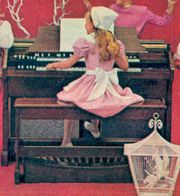

eclipsing the earlier reed organ. The organist here is

making full use of those capabilities: as she plays on both

manuals, her right foot, resting on the expression pedal, is

in control of the volume, freeing her left foot to perform

on the pedalboard. She has carefully adjusted Hammond's

signature drawbars, which are clearly visible just above the

upper manual.

The classic Hammond electronic organ, invented in the 1930s

and popular for decades thereafter. The Hammond brought an

unprecedented degree of musical capacity into the home, far

eclipsing the earlier reed organ. The organist here is

making full use of those capabilities: as she plays on both

manuals, her right foot, resting on the expression pedal, is

in control of the volume, freeing her left foot to perform

on the pedalboard. She has carefully adjusted Hammond's

signature drawbars, which are clearly visible just above the

upper manual.An electronic organ is an electronic keyboard instrument, originally designed to imitate the sound of a pipe organ.

Contents |

Description

Most current electronic organs are not restricted to pipe organ sounds, but contain other voices imitating instruments such as a trilled mandolin which have no corresponding organ stops, and electronic sounds that have no acoustic equivalent.

The main exceptions are some high-quality instruments designed purely as pipe organ replacements, particularly for churches. These are often called pipeless organs. There are also a few hybrid instruments that use pipes for a few main sounds, and electronics for others. Although many musicians hotly debate the sound quality of electronic organs compared to pipe organs, many churches that are unable to afford costly pipe organs have turned to less-expensive electronic organs as a viable alternative; even a congregation that could afford a modest pipe organ may instead opt for a digital organ that simulates a much larger pipe organ than they could afford. Digital organs may also reduce maintenance costs, as tuning and repairing pipe organs is very costly.

Early history

The immediate predecessor of the electronic organ was the harmonium, or reed organ, an instrument that was very popular in homes and small churches in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In a fashion not totally unlike that of pipe organs, reed organs generated sound by forcing air over a set of reeds by means of a bellows, usually operated by constantly pumping a set of pedals. While reed organs had limited tonal quality, they were small, inexpensive, self-powered, and self-contained. The reed organ was thus able to bring an organlike sound to venues that were incapable of housing or affording pipe organs. This concept was to play an important role in the development of the electric organ.

Electricity arrived on the organ scene in the first decades of the 1900s, but it was slow to have a major impact. Electrically-powered reed organs appeared during this period, but their tonal qualities remained much the same as the older, foot-pumped models. Meanwhile, some experimentation with producing sound by electric impulses was taking place in the first decades of the twentieth century, especially in France. The first widespread success in this field, however, was a product of the Hammond Corporation in the mid-1930s. The Hammond Organ quickly became the successor of the reed organ, displacing it completely.

From the first, however, electronic organs operated on a radically different principle from all previous organs. In the place of reeds and pipes, Hammond introduced a set of rapidly spinning magnetic wheels, called tonewheels, which served as transducers that generated electrical signals of various frequencies that were fed through an amplifier to a loudspeaker. The organ was electrically powered, replacing the reed organís twin bellows pedals with a single swell (or "expression") pedal more like that of a pipe organ. Instead of having to pump at a constant rate, as had been the case with the reed organ, the organist simply varied her pressure on this pedal at will to change the volume as she desired. Unlike reed organs, this gave her great control over her music's dynamic range, while at the same time freeing one or both of her feet to play on a pedalboard, which, unlike nearly all reed organs, electronic organs incorporated. From the beginning, the electronic organ also had a second manual, also very rare among reed organs. While they meant that the electronic organ required greater musical skills of the organist than the reed organ had, the second manual and the pedalboard along with the expression pedal greatly enhanced her playing, far surpassing the reed organ's limited capabilities.

The most revolutionary difference in the Hammond, however, was its huge number of tonewheel settings, achieved by manipulating a system of drawbars located near the manuals. By using the drawbars, the organist could combine a variety of electronic tones in varying proportions, thus giving the Hammond vast "registration." In all, the Hammond was capable of producing more than 250 million tones. This feature, combined with the three-keyboard layout (i.e., manuals and pedalboard), the freedom of electrical power, and a wide, easily controllable range of volume made the first electronic organs far more flexible than any reed organ, or indeed any other musical instrument in history except, perhaps, for the pipe organ itself.

In the wake of the Hammond Organís invention, later models--especially those of competitors--used various combinations of oscillators and filters to produce electric tones. Today, however, modern electronic organs use high-quality digital samples to produce as accurate a sound as possible. The heat generated by early models with vacuum tube tone generators and/or amplifiers led to the somewhat derogatory nickname "toaster"; todayís solid-state instruments do not suffer from this problem.

Electronic organs were once popular home instruments, comparable in price to pianos and frequently sold in department stores. After their dťbut in the 1930s, they captured the public imagination, largely through the film performances of Hammond organist Ethel Smith. Nevertheless, they initially suffered in sales during the Great Depression and World War II. After the war they became more widespread, peaking in popularity in the 1950s and early 1960s, but undoubtedly undercut by the rapid growth of television and high fidelity audio systems as home entertainment alternatives during that same period. Home electronic organ models usually attempted to imitate the sounds of theatre organs and/or Hammonds, rather than classical organs.

The 1950s and 1960s

The spinet organ

Following World War II, most electronic home organs were built in a configuration usually called a spinet organ, which first appeared in 1949. These compact and relatively inexpensive instruments became the natural successors to the reed organs. They were marketed as competitors of home pianos and often aimed at would-be home organists who were already pianists (hence the name "spinet," a small upright piano). The instrument's design reflected this concept: the spinet organ physically resembled a piano, and it presented simplified controls and functions that were both less expensive to produce and less intimidating to learn. One feature of the spinet was automatic chord generation; with many models, the organist could produce an entire chord to accompany her melody merely by playing the tonic note, i.e., a single key, on a special section of the manual.

A typical spinet organ of the 1950ís. Note the resemblance

in size and shape to a small home piano. Note also the

shortened, offset manuals and miniature pedalboard, both

sure signs of the spinet.

A typical spinet organ of the 1950ís. Note the resemblance

in size and shape to a small home piano. Note also the

shortened, offset manuals and miniature pedalboard, both

sure signs of the spinet.

On spinet organs the keyboards were typically at least an octave shorter than is normal for organs, with the upper manual missing the bass, and the lower manual missing the treble. The manuals were usually offset, inviting (although not requiring) the new organist to dedicate her right hand to the upper manual and her left to the lower, rather than using both hands on a single manual. This seemed designed in part to encourage the pianist, who was accustomed to a single keyboard, to make use of both manuals. Stops on such instruments, relatively limited in number, were frequently named after orchestral instruments that they could, at best, only roughly approximate, and were often brightly colored (even more so than those of theatre organs). The spinet organ's loudspeaker, unlike the original Hammond models of the 1930s and 1940s, was housed within the main instrument (behind the kickboard), which saved even more space, although it produced a sound inferior to that of free-standing speakers.

The spinet organís pedalboard normally spanned only a single octave, was often incapable of playing more than one note at a time, and was effectively playable only with the left foot (and on some models only with the left toes). This limitation, combined with the shortened manuals, made the spinet organ all but useless for performing or practicing classical organ music, but at the same time it allowed the novice home organist to explore the challenge and flexibility of simultaneously playing three keyboards (two hands and one foot). The expression pedal was located to the right and either partly or fully recessed within the kickboard, thus conveniently reachable only with the right foot. This arrangement spawned a style of casual organist who would naturally rest her right foot on the expression pedal the entire time she played, unlike classically-trained organists or performers on the earlier Hammonds. This position, in turn, instinctively encouraged her to pump the pedal while playing, especially if she was already accustomed to using a pianoís sustain pedal to shape her music. Her expressive pumping added a strong dynamic element to home organ music that much classical literature and hymnody lacked, and would help influence a new generation of popular keyboard artists.

The chord organ

Shortly after the debut of the spinet the "chord organ" appeared. This was an even simpler instrument designed for those who wanted to produce an organlike sound in the home without having to learn much organ (or even piano) playing technique. The chord organ had only a single manual that was usually an octave shorter than its already-abbreviated spinet counterpart. It relied more heavily on automatic chord generation than other models; it also possessed scaled-down registration and no pedalboard or expression pedal (volume being determined by a knob near the manual instead, an inefficient arrangement that effectively eliminated the dynamic playing that an expression pedal allowed). As was the case with the spinet, the loudspeaker was housed within the kickboard.

A typical console organ of the early 1960s. Considerably

larger and more imposing than the spinet, it resembles the

console of a pipe organ (yet this advertisement makes a

point of emphasizing that even children are capable of

mastering it, as the girl here is demonstrating). Note the

five-octave in-line manuals, the extra drawbars, and the

full pedalboard, all of which make this a more complex, but

also a more powerful and flexible, instrument than the

spinet.

A typical console organ of the early 1960s. Considerably

larger and more imposing than the spinet, it resembles the

console of a pipe organ (yet this advertisement makes a

point of emphasizing that even children are capable of

mastering it, as the girl here is demonstrating). Note the

five-octave in-line manuals, the extra drawbars, and the

full pedalboard, all of which make this a more complex, but

also a more powerful and flexible, instrument than the

spinet.

The console organ

On the other end of the spectrum were larger and more expensive home models, known as ďconsole organsĒ because they resembled pipe organ consoles. These instruments had a more traditional configuration, including full-range manuals, a wider variety of stops, and a two-octave (or occasionally even a full thirty-two note) pedalboard easily playable by both feet in standard toe-and-heel fashion. (Console organs having thirty-two note boards were sometimes known as "concert organs.") Console models, like spinet and chord organs, had their speakers mounted above the pedals, though the classic Hammond design of the 1930s and 1940s made use of free-standing loudspeakers, usually manufactured by Leslie, that produced a higher-quality sound than a spinet organís small built-in speakers. With their more traditional configuration, greater capabilities, and better performance compared to spinets, console organs were especially suitable for use in small churches, public performance, and even organ instruction. The home musician or young student who first learned to play on a console model often found that she could later make the transition to a pipe organ in a church setting with relative ease.

By the 1960s, electronic organs were ubiquitous in all genres of popular music, from Lawrence Welk to acid rock and the Wild Mercury Sound of the Bob Dylan album Blonde on Blonde. In some cases, Hammonds were used, while in others, very small all-electronic instruments, only slightly larger than a modern digital keyboard, called "combo organs," were used. (Various organs made by Farfisa were especially popular, and remain so among retro-minded rock combos.) The 1970s and 1980s saw increasing specialization: the jazz scene continued to make heavy use of Hammonds, while various styles of rock began to take advantage of more and more complex electronic keyboard instruments as Large-scale integration and then digital technology began to enter the mainstream. The original Hammond tonewheel design, phased out in the mid-1970s, is still very much in demand by professional organists, and the industry continues to see a lively trade in refurbished instruments even as technological advance allows new organs to perform at levels unimaginable only two or three decades ago.

Frequency divider organs

With the development of the transistor, electronic organs that used no mechanical parts to generate the waveforms became practical. The first of these was the frequency divider organ, the first of which used twelve oscillators to produce one octave of chromatic scale, and frequency dividers to produce other notes. These were even cheaper and more portable than the Hammond. Later developments made it possible to run an organ from a single radio frequency oscillator.

Frequency divider organs were built by many companies, and also offered in kit form to be built by hobbyists.

A few of these have seen notable use, such as the Lowrey played by Garth Hudson. Its electronic design made the Lowrey easily equipped with a pitch bend feature that is unavailable for the Hammond, and Hudson built a style around its use.

During the period from the 1940s through approximately the 1970s, a variety of more modest self-contained electronic home organs from a variety of manufacturers were popular forms of home entertainment. These instruments often simplified the traditional organ stops into imitative voicings such as "trumpet" and "marimba" and as technology progressed they increasingly included automated features such as one-touch chords, electronic rhythm and accompaniment devices, and even built-in tape players. These were intended to make playing complete, layered "one-man band" arrangements extremely easy, especially for those not necessarily trained as organists. While a few such instruments are still sold today, their popularity has waned greatly, and many of their functions have been incorporated into more modern and inexpensive portable keyboards. The Lowrey line of home organs is the epitome of this type of instrument.

In the '60s and '70s, a type of simple, portable electronic organ called the combo organ was popular, especially with pop and rock bands, and was a signature sound in the pop music of the period (e.g. The Doors, Iron Butterfly). The most popular combo organs were manufactured by Farfisa and Vox.

The modern electronic organ

A modern electronic organ. Its superficial resemblance to

the modest spinet organ of earlier years is deceptive; this

modelís high performance level, made possible by digital

design, makes it suitable for professional as well as home

use. This instrument is capable of emulating the sound of an

entire orchestra.

A modern electronic organ. Its superficial resemblance to

the modest spinet organ of earlier years is deceptive; this

modelís high performance level, made possible by digital

design, makes it suitable for professional as well as home

use. This instrument is capable of emulating the sound of an

entire orchestra.

Modern professional electronic organs have reached a degree of sophistication, complexity, and expense surpassed only by the pipe organ itself. The consoles of some of these instruments, at first glance, may be almost indistinguishable from those of pipe organs (although a closer examination, as well as the obvious absence of pipes, will quickly reveal the difference). Electronic organs are still made for the home market, but they have been largely replaced by the digital keyboard or synthesizer, which is not only smaller and cheaper than typical electronic organs or traditional pianos, but also far more capable than the most advanced electronic organs of earlier years. Modern digital organs, by the same token, are far more advanced in design and capabilities then their ancestors.

Todayís instruments incorporate digital sampling, MIDI, and Internet connectivity for downloading of music data and instructional materials, as well as making use of floppy disk and media card storage. While electronically they are radically different from their predecessors, their basic appearance makes them instantly identifiable as the latest generation in a long line of electronic organs that now reaches back more than seventy years.

The very best digital organs today have a number of features which distinguish their sound from that of simpler instruments, including the following.

- Multiple digital-to-analog converters, to prevent degradation of sound quality as multiple stops are used (simpler instruments multiplex one or two DACs for all stops at once).

- Each note in each register is sampled from that actual pipe, as opposed to simpler instruments in which one sample has its frequency shifted digitally to generate different notes.

- Long samples allow a more realistic envelope, as opposed to repeating a short sample.

- Sampling is done with 24-bit or 32-bit resolution instead of CD-quality 16-bit resolution.

- Sampling is done at a much higher frequency than the 44,100 samples per second of CD-quality audio.

- At least four independent amplifiers to provide a more spacious sound.

- A dedicated high power woofer for the low frequencies of the sound; the best digital organs can thus approach -- though not yet quite attain -- the physical feeling of a real pipe organ.

- Simulated changes of windchest pressure -- when many notes are sounding at once, the air pressure of a real pipe organ will drop slightly, which changes the sound of all the pipes; some electronic organs can simulate this effect.

A digital organ with all the above features can be difficult to tell from the sound of a real pipe organ. Of course, such digital organs will cost more than simpler ones, because such an organ may need to store the equivalent of 40 hours or more of sampled sound. The most advanced digital organs also offer some capabilities rarely found in pipe organs, such as changing between equal temperament and one or more historic tuning systems merely by flipping a switch.

For hybrid organs, which combine actual pipes with electronic stops, an important issue is that pipes change pitch with the weather, but digital audio systems do not. The frequency of sound produced by an organ pipe is determined by its geometry and by the speed of sound in the air within it. The speed of sound changes with the temperature and humidity of the air; therefore the pitch of a pipe organ will change as the weather changes, so the pitch of the digital side in a hybrid instrument must be retuned as needed. The simplest way this can be done is with a manual control that the organist can adjust, but better models can make such adjustments automatically.

See also

External links

- Electone.com

- From the 50s to the 70s, Schober produced a popular line of build-your-own organ kits. Models ranged from spinets up through AGO consoles.

Categories: Organ

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: