Fingering for a C-major

trichord on a

guitar in standard tuning (assuming all six

strings are played).

Fingering for a C-major

trichord on a

guitar in standard tuning (assuming all six

strings are played).In music and music theory, the term chord is used in several different senses. In the most general sense, the term can refer to any meaningful collection of notes that can appear simultaneously, or near-simultaneously. "Chords" in this very general sense are the subject of musical set theory. In more colloquial uses, the term "chord" refers to three or more different notes or pitches sounding simultaneously, or nearly simultaneously, over a period of time. The term is also used in an even more restricted sense, referring to tertian sonorities (see below), that can be constructed as stacks of thirds relative to some underlying scale. Two-note sonorities are typically referred to as dyads or intervals.

The word chord is short for accord, from the Middle English word cord. In the Middle Ages, Western harmony featured the perfect intervals of a fourth, a fifth, and an octave. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the major and minor triads (see below) became increasingly common, and were soon established as the default sonority for Western music. This norm persists to this day in many Western styles, though it is by no means universal. Four-note "seventh chords" have been accepted since the 17th century, and "chords" in jazz often feature five or more notes. Since chords are a well-established norm in Western music, single-note melodies and sonorities of two pitches are often interpreted as implying chords.

Chords are by no means a universal feature of human music, and many non-Western styles do not have "chords" as a Western musician would understand them. For that reason, this article will focus primarily on chords in traditional Western music. For information on non-Western styles, consult the articles specific to those styles.

Contents |

Constructing and naming chords

Instruments playing different

notes can create a chord.

Instruments playing different

notes can create a chord.

Every chord has certain characteristics, which include:

- the number of pitch classes it contains

- the general type of intervals it contains: for example seconds, thirds, or fourths.

- its precise intervallic construction: for example, if it is a triad, is it major, minor, augmented or diminished?

- the scale degree of the root note or bass note

- whether the chord is inverted in register

Number of notes

The easiest way to name a chord is according to the number of pitch classes it contains. Chords with three pitch classes are called trichords. Chords with four notes are known as tetrachords. Those with five are called pentachords, and those with six are hexachords.

Type of interval

- Main article: Interval (music)

Many chords can be arranged as a series whose elements are separated by intervals that are all roughly the same size. For example, a C major triad contains the notes C, E, and G. These notes can be arranged in the series C-E-G, in which the first interval (C-E) is a major third, while the second interval (E-G) is a minor third. Any chord that can be arranged as a series of (major or minor) thirds is called a tertian chord. A chord such as C-D-Eb is a series of seconds, containing a major second (C-D) and a minor second (D-Eb). Such chords are called secundal. The chord C-F-B, which consists of a perfect fourth C-F and an augmented fourth (tritone) F-B is called quartal. Most Western music uses tertian chords.

On closer examination, however, the terms "secundal", "tertian" and "quartal" can become ambiguous. The terms "second," "third," and "fourth" (and so on) are often understood relative to a scale, but it is not always clear which scale they refer to. For example, consider the pentatonic scale G-A-C-D-F. Relative to the pentatonic scale, the intervals G-C and C-F are "thirds," since there is one note between them. Relative to the chromatic scale, however, the intervals G-C and C-F are "fourths" since they are five semitones wide. For this reason the chord G-C-F might be described both as "tertian" and "quartal," depending on whether one is measuring intervals relative to the pentatonic or chromatic scales.

The use of accidentals complicates the picture. The chord B#-E-Ab is notated as a series of diminished fourths (B#-E) and (E-Ab). However, the chord is enharmonically equivalent to (and sonically indistinguishable from) C-E-G#, which is a series of major thirds (C-E) and (E-G#). Notationally, then, B#-E-Ab is a "fourth chord," even though it sounds identical to the tertian chord C-E-G#. In some circumstances it is useful to talk about how a chord is notated, while in others it is useful to talk about how it sounds. Terms such as "tertian" and "quartal" can be used in either sense, and it is important to be clear about which is intended.

Quality and Triads

The quality of a tertian triad is determined by

the precise arrangement of its intervals. Tertian trichords,

known as

triads, can be described as a series of three notes

each of which is a third above its predecessor. The first

element is called the

root note of the chord, the second note is called the

"third" of the chord, and the last note is called the

"fifth" of the chord. Since there are two varieties of

third, there are 2 * 2 = 4 varieties of triad. These are

described below:

| Chord name | Component intervals | Example | Chord symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| major triad | major third | minor third | C-E-G | C, CM, Cma |

| minor triad | minor third | major third | C-Eb-G | Cm, Cmi |

| augmented triad | major third | major third | C-E-G# | C+, C+, Caug |

| diminished triad | minor third | minor third | C-Eb-Gb | Co, Cdim |

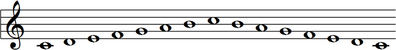

As an example, consider an octave of the C major scale, consisting of the notes C D E F G A B C.

C major scale

C major scale

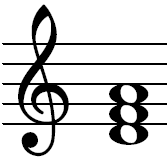

The C major triad consists of the notes C, E and

G

The C major triad consists of the notes C, E and

G

The major triad formed using the C note as the root would consist of C (the root note of the scale), E (the third note of the scale) and G (the fifth note of the scale). This triad is major because the interval from C to E is a major third.

The D minor triad consists of the notes D, F and

A

The D minor triad consists of the notes D, F and

A

Using the same scale (and thus, implicitly, the key of C major) a minor chord may be constructed using the D as the root note. This would be D (root), F (third note) A (fifth note).

Examination at the piano keyboard will reveal that there are four semitones between the root and third of the chord on C, but only 3 semitones between the root and third of the chord on D (while the outer notes are still a perfect fifth apart). Thus the C triad is major while the D triad is minor.

A triad can be constructed on any note of the C major scale. These will all be either minor or major, with the exception of the triad on B, the leading-tone (the last note of the scale before returning to a C, in this case), which is diminished. For more detail see the article on the Mathematics of the Western music scale.

Scale degree

Chords are also distinguished and notated by the scale degree of their root note or bass note.

For example, since the first scale degree of the C major scale is the note C, a triad built on top of the note C would be called the one chord, which might be notated 1, I, or even C, in which case the assumption would be made that the key signature of the particular piece of music in question would indicate to the musician what function a C major triad was fulfilling, and that any special role of the chord outside of its normal diatonic function would be inferred from the context.

Roman numerals indicate the root of the chord as a scale degree within a particular key as follows:

| Roman numeral | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| Scale degree | tonic | supertonic | mediant | subdominant | dominant | submediant | leading tone/subtonic |

Many analysts use lower-case Roman numerals to indicate minor triads and upper-case for major ones, with degree and plus signs (o and +) to indicate diminished and augmented triads, respectively. When they are not used, all the numerals are capital, and the qualities of the chords are inferred from the other scale degrees that chord contains; for example, a chord built on VI in C major would contain the notes A, C, and E, and would therefore be a minor triad.

The scale to whose scale degrees the Roman numerals refer may be indicated to the left (e.g. F#:), but may also be understood from the key signature or other contextual clues.

Unlike pop chord symbols, which are used as a guide to players, Roman numerals are used primarily as analytical tools, and so indications of inversions or added tones are sometimes omitted if they are not relevant to the analysis being performed.

Inversion

When the bass note is not the same as the root note, the chord is said to be inverted.

The number of inversions that a chord can have is one less than the number of chord members it contains. Triads, for example, (having three chord members) can have three positions, two of which are inversions:

- Root position: The root note is in the bass, and above that are the third and the fifth. In the first scale degree this is marked 'I'

- First inversion: The third is in the bass, and above it are the fifth and the root. This creates an interval of a sixth and a third above the bass note, and so is marked in figured Roman notation as '6/3'. This is commonly abbreviated to '6' (or 'Ib') since the sixth is the characteristic interval of the inversion, and so always implies '6/3'.

- Second inversion: The fifth is in the bass, and above it are the root and the third. This creates an interval of a sixth and a fourth above the bass note, and so is marked as '6/4' or 'Ic'. Second inversion is the most unstable chord position.

-

Inverted triads

- the first three chords played are C major root position, first inversion, second inversion; then C minor root position, first inversion, second inversion.

Common chords

Seventh chords

Seventh chords may be thought of as the next natural step in composing tertian chords after triads. Seventh chords are constructed by adding a fourth note to a triad, at the interval of a third above the fifth of the chord. This creates the interval of a seventh above the root of the chord. There are various types of seventh chords depending on the quality of the original chord and the quality of the seventh added.

Five common types of seventh chords have standard symbols. The chord quality indications are sometimes superscripted and sometimes not (e.g. Dm7, Dm7, and Dm7 are all identical). The last three chords are not used commonly except in jazz.

| Chord name | Component notes (chord and interval) | Chord symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| major seventh | major triad | major seventh | CMaj7, CMA7, CM7, CΔ |

| dominant seventh | major triad | minor seventh | C7, C7 |

| minor seventh | minor triad | minor seventh | Cm7, C-7 |

| diminished seventh | diminished triad | diminished seventh | Co7, Cdim7 |

| half-diminished seventh | diminished triad | minor seventh | Cø7, Cm7b5 |

| augmented major seventh | augmented triad | major seventh | C+(Maj7), CAM7, CMaj7+5, CMaj7#5 |

| augmented seventh | augmented triad | minor seventh | C+7, C7+5, C7#5 |

| minor major seventh | minor triad | major seventh | Cm(Maj7) |

When a dominant seventh chord is borrowed from another key, the Roman numeral corresponding with that key is shown after a slash. For example, V/V indicates the dominant of the dominant. In the key of C major, where the dominant (V) chord is G major, this secondary dominant is the chord on the fifth degree of the G major scale, i.e. D major. Note that while the chord built on D (ii) in the key of C major would normally be a minor chord, the V/V chord, also built on D, is major.

Extended chords

Extended chords are tertian chords (built from thirds) or triads with notes extended, or added, beyond the seventh. Thus ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords are extended chords. After the thirteenth, any notes added in thirds duplicate notes elsewhere in the chord, so there are no fifteenth chords, seventeenth chords, and so on.

To add one note to a single triad, the equivalent simple intervals are used. Because an octave has seven notes, these are as follows:

| Chord name | Component notes (chord and interval) | Chord symbol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add nine | major triad | ninth | - | C/9, Cadd9 |

| Major fourth | major triad | eleventh | - | C4 |

| Major sixth | major triad | thirteenth | - | C6 |

| Six-nine | major triad | ninth | thirteenth | C6/9, CΔ |

| Dominant ninth | dominant seventh | major ninth | - | C9 |

| Dominant eleventh | dominant seventh | perfect eleventh | - | C11 |

| Dominant thirteenth | dominant seventh | major thirteenth | - | C13 |

Other extended chords follow the logic of the rules shown above.

Thus Maj9, Maj11 and Maj13 chords are the extended chords shown above with major sevenths rather than dominant sevenths. Similarly, m9, m11 and m13 have minor sevenths.

Extended chords composed of triads can also have variations. Thus madd9, m4 and m6 are minor triads with extended notes.

Sixth chords

Sixth chords are chords that contain any of the various intervals of a sixth as a defining characteristic. They can be considered as belonging to either of two separate groups:

Group1: Chords that contain a sixth chord member, i.e., a note separated by the interval of a sixth from the chord's root, such as:

1. The major sixth chord (also called, sixth or added sixth with chord notation: 6, e.g., 'C6')

This is by far the most common type of sixth chord of this group, and comprises a major chord plus a note forming the interval of a major sixth above the root. For example, the chord C6 contains the notes C-E-G-A.

2. The minor sixth chord (with chord notation: min 6 or m6, e.g., Cm6)

This is a minor chord plus a note forming the interval of a major sixth above the root. For example, the chord Cmin6 contains the notes C-Eb-G-A

In chord notation, the sixth of either chord is always assumed to be a major sixth rather than a minor sixth. Minor versions exist, and in chord notation this is indicated as, e.g., Cmin (min6). Such chords, however, are very rare, as the minor sixth chord member is considered an 'avoid tone' due to the semitone clash between it and the chord's fifth.

3. The augmented sixth chord (usually appearing in chord notation as an enharmonically equivalent 'seventh chord')

An augmented sixth chord is a chord which contains two notes that are separated by the interval of an augmented sixth (or, by inversion, a diminished third - though this inversion is rare in compositional practice). The augmented sixth is generally used as a dissonant interval which resolves by both notes moving outward to an octave.

In Western music, the most common use of augmented sixth chords is to resolve to a dominant chord in root position (that is, a dominant triad with the root doubled to create the octave to which the augmented sixth chord resolves), or to a tonic chord in second inversion (a tonic triad with the fifth doubled for the same purpose). In this case, the tonic note of the key is included in the chord, sometimes along with an optional fourth note, to create one of the following (illustrated here in the key of C major):

- Italian Augmented Sixth Chord: A flat, C, F sharp

- French Augmented Sixth Chord: A flat, C, D, F sharp

- German Augmented Sixth Chord: A flat, C, E flat, F sharp

Group 2: Inverted chords, in which the interval of a sixth appears above the bass note rather than the root; inversions, traditionally, being so named from their characteristic interval of a sixth from the bass.

1. Inverted major and minor chords

Inverted major and minor chords may be called sixth chords. More specifically, their first and second inversions may be called six-three (6/3)and six-four (6/4) chords respectively, to indicate the intervals that the upper notes form with the bass note. Nowadays, however, this is mostly done for purposes of academic study or analysis.

2. The neapolitan sixth chord

This chord is a major triad with the lowered supertonic scale degree as its root. The chord is referred to as a "sixth" because it is almost always found in first inversion Though a technically accurate Roman numeral analysis would be ♭II, it is generally labelled N6. In C major, the chord is spelled (assuming root position) D flat, F, A flat.

Because it uses lowered altered tones, this chord is often grouped with the borrowed chords. However, the chord is not borrowed from the parallel major or minor, and may appear in both major and minor keys.

Chromatic alterations

Although the third and seventh of the chord are always determined by the symbols shown above, the fifth, as well as the extended intervals 9, 11, and 13, may be altered through the use of accidentals. These are indicated along with the corresponding number of the element to be altered.

Accidentals are most often used in conjunction with dominant seventh chords. For example:

| Chord name | Component notes | Chord symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seventh augmented fifth | dominant seventh | augmented fifth | C7+5, C7♯5 |

| Seventh flat nine | dominant seventh | minor ninth | C7-9, C7♭9 |

| Seventh augmented eleventh | dominant seventh | augmented eleventh | C7+11, C7♯11 |

| Seventh flat thirteenth | dominant seventh | minor thirteenth | C7-13, C7♭13 |

| Half-diminished seventh | minor seventh | diminished fifth | Cø7, Cm7♭5 |

"Altered" dominant seventh chords (C7alt) have a flat ninth, a sharp ninth, a diminished fifth and an augmented fifth

When superscripted numerals are used, the different numbers may be listed horizontally (as shown), or vertically.

Added tone chords

An added tone chord is a traditional chord with an extra "added" note, such as the commonly added sixth (above the root). This includes chords with an added second (ninth) or fourth (eleventh), or a combination of the three. These chords do not include "intervening" thirds as in an extended chord.

Suspended chords

A suspended chord, or "sus chord" (sometimes improperly called sustained chord), is a chord in which the third has been displaced by either of its dissonant neighbouring notes, forming intervals of a major second or (more commonly), a perfect fourth with the root. This results in two distinct chord types: the suspended second (sus2) and the suspended fourth (sus4). The chords, Csus2 and Csus4, for example, consist of the notes C D G and C F G, respectively. Extended versions are also possible, such as the seventh suspended fourth, for example, which, with root C, contains the notes C F G Bb and is notated as C7sus4.

The name suspended derives from an early voice leading technique developed during the common practice period of composition, in which an anticipated stepwise melodic progression to a harmonically stable note in any particular part (voice) was often momentarily delayed or suspended simply by extending the duration of the previous note. The resulting unexpected dissonance could then be all the more satisfyingly resolved by the eventual appearance of the displaced note.

In modern usage, without regard to such considerations of voice leading, the term suspended is restricted to those chords involving the displacement of the third only, and the dissonant second or fourth no longer needs to be prepared from the previous chord. Neither is it now obligatory for the displaced note to make an appearance at all. However, in the vast majority of occurences of suspended chords, the conventional stepwise resolution to the third is still observed.

Note that the inclusion of the third in either the suspended second or suspended fourth chords negates the effect of suspension, and such chords are properly called added ninth and added eleventh chords rather than suspended chords.

Borrowed chords

Borrowed chords are chords borrowed from the parallel minor or major. If the root of the borrowed chord is not in the original key, then they are named by the accidental. For instance, in major, a chord built on the parallel minor's sixth degree is a "flat six chord", written bVI. Borrowed chords are an example of mode mixture.

If a chord is borrowed from the parallel key, this is usually indicated directly (e.g. IV (minor)) or explained in a footnote or accompanying text.

Polychords

Polychords are two or more chords superimposed on top of one another. See also altered chord, secundal chord, Quartal and quintal harmony and Tristan chord.

Guitar and pop chords

All pop-music chords are assumed to be in root position, with the root of the chord in the bass. To indicate a different bass note, a slash is used, such as C/E, indicating a C major chord with an E in the bass. If the bass note is a chord member, the result is an inverted chord; otherwise, it is known as a slash chord. This is not to be confused with the similar-looking secondary dominants below.

The tables above include a column showing the pop chord symbols commonly used as an abbreviated notation using letters, numbers, and other symbols and usually written above the given lyrics or staff. Although these symbols are used occasionally in classical music as well, they are most common for lead sheets and fake books in jazz and other popular music.

Power chords

Power chords are simple harmonies, in that they do not consist of three or more different kinds of notes, but rather two kinds. They consist of perfect fifths and fourths and lack the third scale note. Often, players double the root or fifth to create a third note, but not a third kind of note. The lack of the third scale note makes their quality ambiguous, which in layman's terms means that it is not clear whether they are major or minor in their flavor. This is due to the fact that the major or minor quality of a chord is directly produced by the third or flatted third scale note. Power chords are generally played on an electric guitar and used extensively in many kinds of rock music (especially heavy metal music) where heavy amounts of distortion are used. Distortion adds a great deal of harmonic content to an electric guitar's timbre. At high distortion levels, perfect intervals are the only intervals with enough consonance to be clearly articulated and perceived. Even the addition of a third can cause a chord to sound unstable and dissonant.

Chord sequence

Chords are commonly played in sequence, much as notes are played in sequence to form melodies. Chord sequences can be conceptualised either in a simplistic way, in which the root notes of the chords play simple melodies while tension is created and relieved by increasing and decreasing dissonance, or full attention can be paid to each note in every chord, in which case chord sequences can be regarded as multi-part harmony of unlimited complexity.

-

Chord sequence

- from Erik Satie's Sarabande no. 3

Nonchord tones and dissonance

A nonchord tone is a dissonant or unstable tone which is not a part of the chord that is currently playing and in most cases quickly resolves to a chord tone.

Simultaneity

A chord is only the harmonic function of a group of notes, and it is unnecessary for all the notes to be played together (called forming a simultaneity). For example, broken chords and arpeggios are ways of playing notes in succession so that they form chords. One of the most familiar broken chord figures is Alberti bass.

Since simultaneity is not a required feature of chords, there has been some academic dicussion regarding the point at which a group of notes can be called a chord. Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990, p.218) explains that, "we can encounter 'pure chords' in a musical work," such as in the "Promenade" of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition.

Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition

"Promenade"

Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition

"Promenade"

However, "often, we must go from a textual given to a more abstract representation of the chords being used," as in Claude Debussy's Première Arabesque. The chords on the second stave shown here are abstracted from the notes in the actual piece, shown on the first. "For a sound configuration to be recognized as a chord, it must have a certain duration."

Goldman (1965, p.26) elaborates: "the sense of harmonic relation, change, or effect depends on speed (or tempo) as well as on the relative duration of single notes or triadic units. Both absolute time (measurable length and speed) and relative time (proportion and division) must at all times be taken into account in harmonic thinking or analysis."

References

- Dahlhaus, Carl. Gjerdingen, Robert O. trans. (1990). Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, p.67. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691091358.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and

Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Musicologie

générale et sémiologue, 1987). Translated by Carolyn

Abbate (1990).

ISBN 0691027145.

- Goldman (1965).

Further reading

- Twentieth Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice by Vincent Persichetti, ISBN 0393095398.

- Benward, Bruce & Saker, Marilyn (2002). Music in Theory and Practice, Volumes I & II (7th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-294262-2.

- Károlyi, O Introducing Music. England: Penguin Books.

- Piston, Walter (1987). Harmony (5th ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95480-3.

External links

- G-Tabulatures Learn guitar with free tabs

- Basic Guitar Chord Chart Learn the basic guitar chords and shortly be able to play just about any song

- Jazz Guitar Chords

- Jazz Chord Voicings

- Chords Generator

- Guitar Chord Finder

- Chord Theory (Chord theory for Mandolins, Mandolas etc)

- Gootar Piano and Guitar chord generator Over 8,000,000 chords in Standard and alternative tunings. Design printable chord charts.

- Guitariff Chord dictionnary, Guitar Pro tabs & exercises.

- Visual Guitar Guitar scales, modes, and apreggio viewer program and fretboard theory

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: