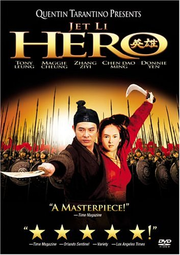

Poster from the American release of Zhang Yimou's

2002 film Hero (英雄)

Poster from the American release of Zhang Yimou's

2002 film Hero (英雄)

Wǔxiá (also Wu Xia) (Traditional Chinese: 武俠; Simplified Chinese: 武侠; Mandarin IPA: [wuɕiɑ]; Cantonese: mów hàb), literally meaning "martial arts chivalry" or "martial arts heroes", from Chinese, is a distinct genre in Chinese literature, television and cinema. Wuxia figures prominently in the popular culture of all Chinese-speaking areas, and the most important writers have devoted followings.

The wuxia genre is particular to Chinese culture, because it is a unique blend of the martial arts philosophy of xia (俠, "chivalry", "a chivalrous man or woman") developed down the centuries, and the country's long history in wushu. In Japan, samurai bushido traditions share some aspects with Chinese martial xia philosophy. Although the xia or "chivalry" concept is often translated as "knights", "chivalrous warriors" or "knights-errant", most xia aspects are so rooted in the social and cultural milieu of ancient China that it is impossible to find an exact translation in the Western world.

Contents |

History and Context

Earlier precedents

Wuxia stories have their roots in some early youxia (游侠, "wanderers") and cike (刺客, "assassin") stories around 2nd to 3rd century BC, such as the assassination attempts of Jing Ke and Zhuan Zhu (专诸) listed in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. In the section entitled "Assassins" (刺客列传), Sima Qian outlined a number of famed assassins in the Warring States who were entrusted with the (then considered noble) task of political assassination. These were usually ci ke (刺客) who resided in the residences of feudal lords and nobilities, rendering services and loyalties much in the manner of Japanese samurais. In another section, "Roaming Xia" (游侠列传), he detailed many embryonic features of the xia culture of his day. This popular phenomenon continues to be documented in historical annals like The Book of the Han (汉书) and The Later Book of the Han (后汉书).

Xiake stories made a strong comeback in the Tang dynasty in the form of Chuanqi (传奇, literally "legendary") tales. Stories like Nie Yin Niang (聂隐娘), The Slave of Kunlun (昆仑奴), Jing Shi San Niang (荆十三娘), Red String (红线) and The Bearded Warrior (虬髯客) served as prototypes for modern wuxia stories, featuring fantastic, out-of-the-world protagonists, often loners, who performed daring heroic deeds.

The earliest full-length novel that could be considered part of the genre was Water Margin, written in the Ming Dynasty, although some would classify parts of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms as a possible earlier antecedent. The former was a political criticism of the deplorable socio-economical state of the late Ming Dynasty, whilst the latter was an alternative historical retelling of the post-Han Dynasty's state of three kingdoms. Water Margin's championing of outlaws with a code of honor was especially influential in the development of Jianghu culture. Three Kingdoms contained many classic close combat descriptions which were later borrowed by wuxia writers.

Many works in this vein during the Ming and Qing dynasties were lost due to prohibition by the government. The ethos of personal freedom and conflict-readiness of these novels were seen as seditious even in times of peace and stability. The departure from mainstream literature also meant that patronage of this genre was limited to the masses and not to the literati, and stifled some of its growth. Nonetheless, the genre continued to be enormously popular, with certain full-length novels such as The Strange Case of Shi Gong (施公案奇闻) and The Romance of the Heroic Daughters and Sons (儿女英雄传) cited as the clearest nascent wuxia novels. Justice Bao stories seen in San Xia Wu Yi (三侠五义) and Xiao Wu Yi (小五义) incorporated much of social justice themes of later wuxia stories.

20th century

Modern Wuxia

Wuxia novels now constitute a highly popular fiction genre in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Wuxia novels, especially by eminent authors like Jinyong and Gu Long, have a devoted niche following there, not unlike fantasy or science fiction in the West.

Important wuxia novelists include:

Jinyong

Gu Long

Huang Yi

Wen Rui'an

Liang Yusheng

Sima Ziyan

Xiao Yi

Many of the most popular works, such as the works by Jinyong, has been repeatedly converted into films and TV series in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China. In addition, the study of Jinyong's work has created an independent branch of study called Jinology. With the advent of the digital age, countless wuxia stories written by amateur authors circulate the Internet, and the genre faces a mini-resurgence in recent years.

Themes

Plot and setting

Modern wuxia stories are historical adventure stories.

A common plot typically features a young protagonist, usually male, in ancient China, who experiences a tragedy (e.g. the loss of a family or a parent), goes through exceeding hardship and arduous trials, and studies under a great master of martial arts, or comes into possession of a long-lost scroll or manual containing unrivalled martial arts information. Eventually the protagonist emerges as a supreme martial arts master unequalled in all of China, who then proffers his skills chivalrously to mend the ills of the "Jianghu" world. Luke Skywalker from Star Wars would be a Western counterpart to this type of hero.

Another common thread would involve a mature, extremely skillful hero with a powerful nemesis who is out for revenge, and the storyline would culminate in a final showdown between the protagonist and his nemesis. The most familiar example in Western culture of this type of wuxia hero might be The Lone Ranger, especially in his repeated confrontations with Butch Cavendish.

Other novels, especially those by Gu Long, create detective-type and romance stories in the setting of ancient China.

Philosophy of Xia

To understand the concept of xia from a Western perspective, consider the Robin Hood mythology: an honourable and generous person who has considerable martial skills which he puts to use for the general good rather than towards any personal ends, and someone who does not necessarily obey the authorities.

Foremost in the xia's code of conduct are yi ("righteousness") and xin (honour???), which emphasize the importance of gracious deed received or favours (恩 ēn) and revenge (仇 chóu) over all other ethos of life. Nevertheless, this code of the xia is simple and grave enough for its adherents to kill and die for, and their vendetta can pass from one generation to the next until resolved by retribution, or, in some cases, atonement. The xia is to expected to aid the person who needed help, usually the masses, who are down-trodden. Not all martial artists uphold such a moral code, but those who do are respected, revered and bestowed the honor of being referred to as a xia.

Jiang Hu

Jiang Hu (江湖) (Cantonese: Gong Woo), (literally means "rivers and lakes") is the wuxia parallel universe - the alternative world of martial artists and pugilists, usually congregrating in sects, disciplines and schools of martial arts learnings. It has been described as a kind of "shared world" alternate universe, inhabited by wandering swordspersons, thieves and beggars, priests and healers, merchants and craftspeople. The best wuxia writers draw a vivid picture of the intricate relationships of honor, loyalty, love and hatred between individuals and between communities within this milieu.

A common aspect to jiang hu is the tacit suggestion that the courts of law or courts of jurisdiction are dysfunctional, or are simply powerless to mandate the Jiang Hu world. Differences may be resolved by way of force, but the use of force must be righteous and ethical, predicating the need for xia and their chivalrous ways. Law and order is maintained by the alliance of wulin (武林), the society of martial artists. They are elected and commanded by the most able xias. This alliance leader is an arbiter, who presides and adjudicates over inequities and disputes. He is a de jure chief justice of the affairs of the jiang hu.

Martial arts

Although wuxia is based on true-life martial arts, the genre elevates the mastery of their crafts into fictitious levels of attainment. Combatants have the following skills:

- fighting, usually using a codified sequence of movements known as zhāo (招) where they would have the ability to withstand armed foes.

- use of everyday objects such as ink brushes, abaci, and musical instruments as lethal weapons, and the adept use of assassin weapons (ànqì 暗器) with accuracy

- use of qīnggōng (T: 輕功 S: 轻功), or the ability to move swiftly and lightly, allowing them to scale walls, glide on waters or mount trees. This is based on real Chinese martial art practices. Real martial art exponents practise qinggong through years of attaching heavy weights on their legs. Its use however is greatly exaggerated in wire-fu movies where they appear to circumvent gravity.

- use of nèilì (内力) or nèijìn (內勁), which is the ability to control mystical inner energy (qi) and direct it for attack or defense, or to attain superhuman stamina.

- ability to engage in diǎnxué (T: 點穴 S: 点穴) also known by its Cantonese pronunciation Dim Mak 點脈, or other related techniques for killing or paralyzing opponents by hitting or seizing their acupressure points (xué 穴) with a finger, knuckle, elbow or weapon. This is based on true-life practices trained in some of the Chinese martial arts, known as dianxue and by the seizing and paralyzing techniques of chin na.

Consistent with Chinese beliefs about the relationship between the physical and paranormal, these skills are usually described as being attainable by anyone who is prepared to devote his or her time in diligent study and practice. The details of some of the more unusual skills are often to be found in abstrusely written and/or encrypted manuals known as mìjí (秘笈), which may contain the secrets of an entire sect, and are often subject to theft or sabotage.

The fantastic feats of martial arts prowess featured in the wuxia novels are substantially fictitious in nature, although there is still widespread popular belief that these skills once existed and are now lost. A popular theory to explain why current martial arts practitioners cannot attain the levels described in the wuxia genre is related to the methodology of passing on the martial arts crafts. Only the favourite pupil of a master gets to inherit the best crafts but the masters tend to keep the most powerful or significant chapter to himself. Hence what we have today at the Shaolin or other schools are but a fraction of what they were centuries earlier. There is little evidence to support this claim.

Suspension of disbelief

Because the wuxia genre occupies a difficult-to-define position between pure fantasy and reality, and many tales are set in clearly defined historical periods, a substantial part of Western and other audiences may have difficulty accepting the conventions of wuxia genre, dismissing them as pure improbability. Paradoxically, this part of the audience may readily embrace the concept of the Force in the Star Wars series, the superhero fantasy subgenre, or the magic in JRR Tolkien's Lord of the Rings or JK Rowling's Harry Potter.

One way to circumvent this is to treat the genre as populist narratives set in a bygone era, much like those in the legendary stories of Greek mythology, the Arthurian legends or Beowulf. Most of these are set in historical periods, with certain fantastic overlays. The fantastic elements does not dismiss their connection with reality.

Another point to note is that most of these martial acts, which are somewhat plausible in writing, tend to become highly exaggerated in films through the use of wireworks. The exaggerations, performed through acrobatics, hidden trampolines, wires and trick editing, are usually justified on grounds of visual aesthetics. The Chinese audience readily accepts them, and voluntarily suspends their disbelief after decades of exposure. Such responses are not unknown in Western cinema as well, such as in the sudden bursting into song and dance in musicals.

Films

House of Flying Daggers (2004)

House of Flying Daggers (2004)

Wuxia film (or wuxia pian, Mo Hap film, Mo Hap Pin) (Traditional Chinese: 武俠片; Simplified Chinese: 武侠片; Pinyin: wǔxiá piān) is a film genre originating in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Because of its distinguishing characteristics (a historical setting, action scenes centred on swordplay, a stronger emphasis towards melodrama and themes of bonding, friendship, loyalty, and betrayal), this genre is considered slightly different to the martial arts film styles. There is a strong link between wuxia films and wuxia novels, and its cinema may be considered an offshoot of those. Many of the films are based on novels; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is an example of this.

The modern form of the genre has existed in the Pacific Rim region since the mid 1960s, although the earliest films date back to the 1920s. King Hu, working from Hong Kong and Taiwan, and the Shaw Studio, working from Hong Kong, were pioneers of the modern form of this genre, featuring sophisticated action choreography with plentiful wire-assisted acrobatics, trampolines and under-cranking.

The storylines in the early films were loosely adapted from existing literature. Actors, actresses, choreographers and directors involved in wuxia films became famous. For example Cheng Pei-Pei and Jimmy Wang-Yu were two of the biggest stars in the days of Shaw Studio and King Hu. Jet Li was a more recent star of wuxia films, having appeared in the Swordsman series and Hero amongst others. Yuen Woo Ping was a choreographer who achieved fame by crafting stunning action-sequences in films of the genre. Mainland Chinese director Zhang Yimou's foray into wuxia films was distinguished by the imaginative use of vivid colours and breathtaking background settings.

Wuxia was introduced to the Hollywood studios in 2000 by Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Following Ang Lee's footsteps, Zhang Yimou made Hero targeted for the international market in 2003, and House of Flying Daggers in 2004. American audiences are also being introduced to wuxia through Asian-television stations in larger cities, which feature well-produced miniseries such as Warriors of the Yang Clan and Paradise, often with English subtitles. With complex, almost soap-opera storylines, lavish sets and costumes, and veteran actors in pivotal roles, these tales can possibly appeal to Western viewers whether or not they catch the subtle nuances.

Wuxia film style has also been appropriated by the West. In 1986, John Carpenter's film Big Trouble in Little China was inspired by the visuals of the genre. The Matrix trilogy has many elements of wuxia, although the heroes and the villains of The Matrix gain their supernatural powers from a different source. Similarly, when Star Wars was released in the late 1970s, many Chinese audiences viewed it as a western wuxia movie set in a futuristic and foreign world (especially the duel between Darth Vader and Obi-Wan Kenobi with lightsabers). The Star Wars prequels showed even more of a western wuxia style.

Significant wuxia films include:

- Torching the Red Lotus Temple (《火燒紅蓮寺》1928) — one of the earliest wuxia movies, followed by 17 sequels until the whole genre was banned by the Chinese government in 1931. Copies of the film were confiscated and burned. In March of 1935, filmmakers in Hong Kong (then a British colony) introduced the 19th episode of the series in Cantonese. Its popularity launched a revival of the series.

Still from a wuxia movie from the 1960s

Still from a wuxia movie from the 1960s

- Ru Lai Shen Zhang (《如來神掌》1964) — Hong Kong's popular black and white wuxia movie series starring Cho Dat Wah (曹達華) and Yu So Chow (于素秋).

- Dragon Gate Inn (《龍門客棧》1966) — King Hu introduces wire-work into the genre. This style is later dubbed wire fu.

- The One-armed Swordsman (1967) — extreme bloodshed and a male hero.

- A Touch of Zen (1971) — King Hu's masterpiece of aesthetic style which would heavily influence later directors, including Western popularizers Ang Lee and Zhang Yimou

- The Magic Blade (《天涯明月刀》1976) — definitive Shaw Brothers wuxia.

- Zu - Warriors from the Magic Mountain (《蜀山:新蜀山劍俠》1983) — Tsui Hark wuxia fantasy.

- Ashes of Time (1994) — Wong Kar-wai arthouse wuxia.

- Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) — genre's debut in Hollywood.

- Hero (2002) — another international box-office success.

- House of Flying Daggers (2004) — globally released wuxia.

- Kung Fu Hustle (2004) - Stephen Chow's mo lei tau (無厘頭) parody of the wuxia genre, and one of the highest grossing films in Hong Kong's history

See also

External links

- Introduction to the Wuxia genre

- Heroic Grace An introduction to Wuxia with an emphasis on explaining the more unlikely elements for Western readers.

- Wuxia pian (with a tripod ad)

- Wuxiapedia: translations of popular Wuxia novels

- A Chinese page on the history of wuxia film

- Zhang Ziyi CSC: Wuxia Fiction

- Wu Xia / Martial Arts World @ Sensasian

- Wuxia Pien With Wuxia film database attached. At Kung Fu Cinema.

- Wuxia Mania Forum The only pure English Wuxia Discussion forum, including translation, tv series, movies, clips, knowledge exchanges

- SPCNet Forums Active and up-to-date discussions of Wuxia fiction, television series and films.

Categories: Film genres

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: