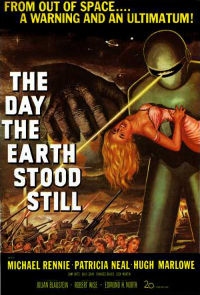

Poster for The Day the Earth Stood Still, an

archetypal science fiction film

Poster for The Day the Earth Stood Still, an

archetypal science fiction film

Science fiction has been a film genre since the earliest days of cinema. Science fiction films have explored a great range of subjects and themes, including many that can not be readily presented in other genres. Science fiction films have been used to explore sensitive social and political issues, while often providing an entertaining story for the more casual viewer. Today, science fiction films are in the forefront of new special effects technology, and the audience has become accustomed to displays of realistic alien life forms, spectacular space battles, energy weapons, faster than light travel, and distant worlds.

There are many memorable sf films, and an even greater number that are mediocre or even among the worst examples of film production. It took many decades, and the efforts of talented teams of film producers, for the science fiction film to be taken seriously as an art form. There is much genre cross-over with science fiction, particularly with horror films (such as Alien (1979)).

Contents |

History

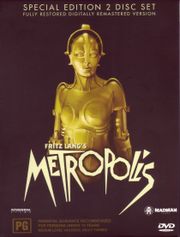

DVD Cover for Metropolis (1927), an

influential science fiction movie from the

silent film era

DVD Cover for Metropolis (1927), an

influential science fiction movie from the

silent film era

Movies that could be categorized as belonging to the science fiction genre first appeared during the silent film era. However these were generally singular efforts that were based on the works of notable authors, such as Fritz Lang's 1927 silent film Metropolis. It was only in the 1950s that the genre came into its own, reflecting the growing output of science fiction pulp magazines and books. But it took Stanley Kubrick's 1968 landmark picture 2001: A Space Odyssey before the genre was taken seriously.

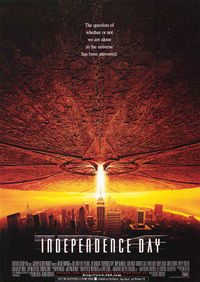

Since that time science fiction movies have become one of the dominant box office staples, pulling in large audiences for blockbuster movies such as Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, Jurassic Park, Independence Day, and The Day After Tomorrow. Science fiction films have been in the forefront of special effects technology, and have been used as a vehicle for biting social commentary for which this genre is ideally suited.

Definition

Defining precisely which movies belong to the science fiction genre is often difficult, as there is no universally accepted definition of the genre, or in fact its underlying genre in literature. According to one definition:

Science fiction film is a film genre which emphasizes actual, extrapolative, or speculative science and the empirical method, interacting in a social context with the lesser emphasized, but still present, transcendentalism of magic and religion, in an attempt to reconcile man with the unknown (Sobchack 63).

This definition assumes that a continuum exists between (real-world) empiricism and (supernatural) transcendentalism, with science fiction film on the side of empiricism, and horror film and fantasy film on the side of transcendentalism. However, there are numerous well-known examples of science fiction horror films, epitomized by such pictures as Frankenstein and Alien. And the Star Wars films blend elements typical of science fiction film (such as spaceships, androids and ray guns) with the mystical "Force", a magical power that would seem to fit the fantasy genre better than science fiction. Movie critics therefore sometimes use terms like "Sci Fi/Horror" or "Science Fantasy" to indicate such films' hybrid status.

The visual style of science fiction film can be characterized by a clash between alien and familiar images. This clash is implemented in the following ways:

- Alien images become familiar

- In A Clockwork Orange, the repetitions of the Korova Milkbar make the alien decor seem more familiar.

- Familiar images become alien

- In Dr. Strangelove, the distortion of the humans make the familiar images seem more alien.

- Alien and familiar images are juxtaposed

- In The Deadly Mantis, the giant praying mantis is shown climbing the Washington Monument.

Cultural theorist Scott Bukatman has proposed that science fiction film is the main area in which it is possible in contemporary culture to witness an expression of the sublime be it through exaggerated scale (the Death Star in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope), apocalypse (Independence Day) or transcendence (2001: A Space Odyssey).

Themes

Independence Day (1996), typical of the

type of contemporary science fiction film that

features action sequences and many special

effects

Independence Day (1996), typical of the

type of contemporary science fiction film that

features action sequences and many special

effects

A science fiction film will be speculative in nature, and often includes key supporting elements of science and technology. However, as often as not the "science" in a Hollywood sci-fi movie can be considered pseudo-science, relying primarily on atmosphere and quasi-scientific artistic fancy than facts and conventional scientific theory. The definition can also vary depending on the viewpoint of the observer. What may seem a science fiction film to one viewer can be considered fantasy to another.

Many science fiction films include elements of mysticism, occult, magic, or the supernatural, considered by some to be more properly elements of fantasy or the occult (or religious) film. This transform the movie genre into a science fantasy with a religious or quasi-religious philosophy serving as the driving motivation. The movie Forbidden Planet employs many common science fiction elements, but the nemesis is a powerful creature with a resemblance to an occult demonic spirit (Some interpretations see it, however, as a manifestation of the Freudian Id, made material by alien superscience). The Star Wars series employed a magic-like philosophy and ability known as the "Force" (see entry on 'Midi-chlorians'). Chronicles of Riddick (2004) included quasi-magical elements resembling necromancy and elementalism.

Some films blur the line between the genres, such as movies where the protagonist gains the extraordinary powers of the superhero. These films usually employ a quasi-plausible reason for the hero gaining these powers. Yet in many respects the film more closely resembles fantasy than sci-fi.

Not all science fiction themes are equally suitable for movies. In addition to science fiction horror, space opera is most common. Often enough, these films could just as well pass as westerns or WWII movies if the science fiction props were removed. Common themes also include voyages and expeditions to other planets, and dystopias, while utopias are rare.

Special effects in science fiction movies range from laughable to ground-breaking. Milestones in this respect include Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Star Wars films, Star Trek: The Motion Picture and, more recently, The Matrix.

Imagery

As was illustrated by Vivian Sobchack, one sense in which the science fiction film differs from the fantasy film is that the former seeks to achieve our belief in the images we are viewing while fantasy instead attempts to suspend our disbelief. The science fiction film displays the unfamiliar and alien in the context of the familiar, thereby making the images appear almost ordinary and even commonplace.

Despite the alien nature of the scenes and science fictional elements of the setting, the imagery of the film is related back to mankind and how we relate to our surroundings. While the sf film strives to push the boundaries of the human experience, they remain bound to the conditions and understanding of the audience and thereby contain prosaic aspects, rather than being completely alien or abstract.

Genre films such as westerns or war movies are bound to a particular area or time period. This is not true of the science fiction film. However there are several common visual elements that are evocative of the genre. These include the spacecraft or space station, alien worlds or creatures, robots, and futuristic gadgets. More subtle visual clues can appear with changes the human form through modifications in appearance, size, or behavior, or by means a known environment turned eerily alien, such as an empty city.

Scientific elements

Peter Sellers as the title character from

Dr. Strangelove, a darkly comic example

of the "mad scientist" character type

Peter Sellers as the title character from

Dr. Strangelove, a darkly comic example

of the "mad scientist" character type

While science is a major element of this genre, many movie studios take significant liberties with what is considered conventional scientific knowledge. Such liberties can be most readily observed in films that show spacecraft maneuvering in outer space. The vacuum should preclude the transmission of sound or maneuvers employing wings, yet the sound track is filled with inappropriate flying noises and changes in flight path resembling an aircraft banking. The film makers assume that the audience will be unfamiliar with the specifics of space travel, and focus is instead placed on providing acoustical atmosphere and the more familiar maneuvers of the aircraft.

Similar instances of ignoring science in favor of art can be seen when movies present environmental effects. Entire planets are destroyed in titanic explosions requiring mere seconds, whereas an actual event of this nature would likely take many hours. A star rises over the horizon of a comet or a Mercury-like world and the temperature suddenly soars many hundreds of degrees, causing the entire surface to turn into a furnace. In reality the energy is initially reaching the ground at a very oblique angle, and the temperature is likely to rise more gradually.

The role of the scientist has varied considerably in the science fiction film genre, depending on the public perception of science and advanced technology. Starting with Dr. Frankenstein, the mad scientist became a stock character who posed a dire threat to society and perhaps even civilization. In the monster movies of the 1950s, the scientist often played a heroic role as the only person who could provide a technological fix for some impending doom. Reflecting the distrust of government that began in the 1960s in the U.S., the brilliant but rebellious scientist became a common theme, often serving a Cassandra-like role during an impending disaster.

Alien life forms

A "Xenomorph"

from the Alien series of movies, one of

the more terrifying depictions of

extraterrestrial life in science fiction films

A "Xenomorph"

from the Alien series of movies, one of

the more terrifying depictions of

extraterrestrial life in science fiction films

The concept of life, particularly intelligent life, having an extra-terrestrial origin is a popular staple of science fiction films. Early films often used alien life forms as a threat or peril to the human race, where the invaders were frequently fictional representations of actual military or political threats on Earth. Later some aliens were represented as benign and even beneficial in nature in such films as E.T. The Extraterrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Aliens in contemporary films are still often depicted as hostile, however, such as those in the Alien series of films.

In order to provide subject matter to which audiences can relate, the large majority of intelligent alien races presented in films have an anthropomorphic nature, possessing human emotions and motivations. Often they will embody a particular human stereotype, such as the barbaric warriors, scientific intellectuals, or priests and clerics. They will frequently appear to be nearly human in physical appearance, and communicate in a common Earth tongue, with little trace of an accent. Very few films have tried to represent intelligent aliens as something utterly different from human kind (e.g. Solaris).

Disaster films

- Main article: Disaster film

A frequent theme among sci-fi films is that of impending or actual disaster on an epic scale. These often address a particular concern of the writer by serving as a vehicle of warning against a type of activity, including technological research. In the case of alien invasion films, the creatures can provide as a stand-in for a feared foreign power.

Disaster films typically fall into the following general categories:

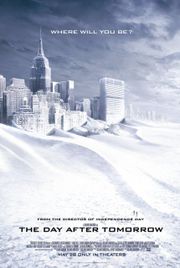

The Day After Tomorrow (2004) depicts a

planetary disaster caused by

Global Warming

The Day After Tomorrow (2004) depicts a

planetary disaster caused by

Global Warming

Alien invasion — hostile extraterrestrials arrive and seek to supplant humanity. They are either overwhelmingly powerful or very insidious. Typical examples include The War of the Worlds (1953, 2005) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, 1978, 1993).

Environmental disaster — such a major climate change, or an asteroid or comet strike. Typical examples include Soylent Green (1973), Armageddon (1998), and The Day After Tomorrow (2004).

Man supplanted by technology — typically in the form of an all-powerful computer, advanced robots or cyborgs, or else genetically-modified humans or animals. Typical examples include The Matrix (1999) and I, Robot (2004).

Nuclear war — usually in the form of a dystopic, post-holocaust tale of grim survival. Typical examples include Dr. Strangelove (1964), The Terminator (1984), and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985).

Pandemic — a highly lethal disease, often one created by man, wipes out most of humanity in a massive plague. Typical examples include The Andromeda Strain (1971), 12 Monkeys (1995), and Outbreak (also 1995).

Time travel movies can also exploit the potential for disaster as a motivation for the plot, or they can be the root cause of a disaster by wiping out recorded history and creating a new future. For example, The Terminator series of films employs time travel in this fashion (see also "Time travel" below).

Monster films

While not usually depicting danger on a global or epic scale, science fiction film also has a long tradition of movies featuring monster attacks. These differ from similar films in the horror or fantasy genres because science fiction films typically rely on a scientific (or at least pseudo-scientific) rationale for the monster's existence, rather than a supernatural or magical reason. Often, the science fiction film monster is created, awakened, or "evolves" because of the machinations of a mad scientist, a nuclear accident, or a scientific experiment gone awry. Typical examples include The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), the Godzilla series of films, and Jurassic Park (1993).

Many such films could be classified as either science fiction or horror (or in fact, both). Examples include such iconic films as Alien, Creature from the Black Lagoon and Frankenstein, as well as diverse offerings like Deep Blue Sea, Resident Evil and The Thing.

Mind and identity

The core mental aspects of what makes us human has been a staple of science fiction films, particularly since the 1980s. Blade Runner examined what made an organic-creation a human, while the RoboCop series saw a android mechanism fitted with the brain and reprogrammed mind of a human to create a cyborg. The idea of brain transfer was not entirely new to science fiction film, as the concept of the "mad scientist" transferring the human mind to another body is as old as Frankenstein.

The human cyborg RoboCop

The human cyborg RoboCop

In the 1990s, Total Recall began a thread of films that explored the concept of reprogramming the human mind. This was reminiscient of the brainwashing fears of the 1950s that appeared in such films as A Clockwork Orange and The Manchurian Candidate. The cyberpunk film Johnny Mnemonic used the reprogramming concept for a commercial purpose as the human became a data transfer vessel. Voluntary erasure of memory is further explored as themes of the films Paycheck and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. In Dark City, human memory and the fabric of reality itself is reprogrammed wholesale. Serial Experiments Lain also explores the idea of reprogrammable reality and memory.

The idea that a human could be entirely represented as a program in a computer was a core element of the film Tron. This would be further explored in The Lawnmower Man, and the idea reversed in Virtuosity as a computer program sought to become a real person. In the Matrix series, the virtual reality world became a real world prison for humanity, managed by intelligent machines. In eXistenZ, the nature of reality and virtual reality become intermixed with no clear distinguishing boundary. Likewise The Cell intermixed dreams and virtual reality, creating a fantasy realm with no boundaries.

Robots

Robots have been a part of science fiction since the Czech playwright Karel Čapek coined the word in 1881. In early films, robots were usually played by a human actor in a boxy metal suit, as in The Phantom Empire. The robot girl in Metropolis is an exception to that rule. The first sophisticated robot in an American film was played by Michael Rennie in The Day the Earth Stood Still (and yes, at least in the original story, the character played by Michael Rennie was the robot). Robots in film have become increasingly advanced in design, although they seldom resemble the real robots now used in automated industry. They usually look human, but walk stiffly and talk with a flat affect. Robots in films are often sentient and sometimes sentimental. Popular example include C3PO and R2D2 from Star Wars. Robots have filled the roles of supporting hero, sidekick, extra (often to confirm that the film in question is set in the future), villain, or monster and in some cases have been the leading characters. One popular theme is whether robots will someday replace man, a question raised in the film adaptation of Isaac Asimov's I, Robot.

Time travel

Back to the Future (1985), a popular

example of time travel in science fiction film

Back to the Future (1985), a popular

example of time travel in science fiction film

The concept of time travel, or travelling backwards and forwards through time, has always been a popular staple of science fiction film, as well as in various sci-fi television series. This usually involves the use of some type of advanced technology, such as H. G. Wells' classic The Time Machine, or the Back to the Future trilogy. Other movies have employed Special Relativity to explain travel far into the future, including the Planet of the Apes series.

More conventional time travel movies use technology to bring the past to life in the present (or a present that lies in our future). The movie Iceman (1984) dealt with the reanimation of a frozen Neanderthal (similar to the 1950 Christopher Lee film Horror Express), a concept later spoofed in the comedy Encino Man (1992). The Jurassic Park series portrayed cloned life forms grown from DNA ingested by insects that were frozen in amber. The movie Freejack (1992) has victims of horrible deaths being pulled forward in time just a split-second before their demise, and then used for spare body parts.

A common theme in time travel movies is dealing with the paradoxical nature of travelling to the past. The film La Jetée (1962) has a self-fulfilling quality as the main character as a child witnesses the death of his future self. It famously inspired 12 Monkeys (1995). In Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) the main character jumps backwards and forwards across his life, and ultimately accepts the inevitability of his final fate.

The Back to the Future series goes one step further and explores the result of altering the past, while in Star Trek: First Contact (1996) the crew must rescue the Earth from having its past altered by time-travelling aliens. The Terminator series employs self-aware machines instead of aliens, which travel to the past in order to gain victory in a future war.

Film versus literature

When compared to literary works, such films are an expression of the genre that often rely less on the human imagination and more upon the visual uniqueness and fanciful imagery provided through special effects and the creativity of artists. The special effect has long been a staple of science fiction films, and, especially since the 1960s and 1970s, the audience has come to expect a high standard of visual rendition in the product. A substantial portion of the budget allocated to a sci-fi film can be spent on special effects, and not a few rely almost exclusively on these effects to draw an audience to the theater (rather than employing a substantial plot and engaging drama).

Science fiction literature often relies upon story development, reader knowledge, and the portrayal of elements that are not readily displayed in the film medium. In contrast, science fiction films usually must depend on action and suspense to entertain the audience, thus favoring battle scenes and threatening creatures over the more subtle plot elements of a drama, for example. There are, of course, exceptions to this trend, and some of the most critically-acclaimed sci-fi movies have relied primarily on a well-developed story and unusual ideas, instead of physical conflict and peril. Nevertheless, few science fiction books have been made into movies, and even fewer successfully.

Science fiction as social commentary

A Clockwork Orange (1971) features

social commentary on violence, psychotherapy,

youth gangs, and other topics

A Clockwork Orange (1971) features

social commentary on violence, psychotherapy,

youth gangs, and other topics

This film genre has long served as a vehicle for thinly-disguised and often thoughtful social commentary. Presentation of issues that are difficult or disturbing for an audience can be made more acceptable when they are explored in a future setting or on a different, earth-like world. The altered context can allow for deeper examination and reflection of the ideas presented, with the perspective of a viewer watching remote events.

The type of commentary presented in a science fiction film often an illustrated the particular concerns of the period in which they were produced. Early sci-fi films expressed fears about automation replacing workers and the dehumanization of society through science and technology. Later films explored the fears of environmental catastrophe or technology-created disasters, and how they would impact society and individuals.

The monster movies of the 1950s—like Godzilla (1954)—served as stand-ins for fears of nuclear war, communism and views on the cold war. In the 1970s, science fiction films also became an effective way of satirizing contemporary social mores with Silent Running and Dark Star presenting hippies in space as a riposte to the militaristic types that had dominated earlier films, Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange presenting a horrific vision of youth culture, Logan's Run depicting a futuristic swingers society and The Stepford Wives anticipating a reaction to the women's liberation movement.

Enemy Mine demonstrated that the foes we have come to hate are often just like us, even if they appear alien. Movies like 2001, Jurassic Park, Blade Runner, and Tron examined the dangers of advanced technology, while RoboCop, 1984, and the Star Wars films illustrate the dangers of extreme political control. Both Planet of the Apes and The Stepford Wives commented on the politics and culture of contemporary society.

Contemporary science fiction films continue to explore social and political issues. One recent example would be 2002's Minority Report, debuting in the months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and focused on the issues of police powers, privacy and civil liberties in the near-future United States.

Influence of classic sci-fi authors

Jules Verne was the first major science fiction author to be adapted for the screen with Melies Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1907), but these only used Verne's basic scenarios as a framework for fantastic visuals. By the time Verne's work fell out of copyright in 1950 the adaptations were treated as period pieces. His works have been adapted a number of times since then, including 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in 1954, From the Earth to the Moon in 1958, and Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1959.

H. G. Wells has had better success with The Invisible Man, Things to Come and The Island of Doctor Moreau all being adapted during his lifetime with good results while The War of the Worlds was updated in 1953 and again in 2005, adapted to film at least four times altogether. The Time Machine has had two film versions (1961 and 2002) while Sleeper in part is a pastiche of Wells' 1910 novel The Sleeper Awakes.

With the drop off in interest in science fiction films during the 1940s few of the 'golden age' sci-fi authors made it to the screen. A novella by John W. Campbell provided the basis for The Thing from Another World (1951). Robert A. Heinlein contributed to the screenplay for Destination Moon in 1950, but none of his major works were adapted for the screen until the 1990s: The Puppet Masters in 1994 and Starship Troopers in 1997. L. Ron Hubbard had to wait until 2000 for the disastrous flop Battlefield Earth. Isaac Asimov can rightly be cited as an influence on the Star Wars and Star Trek films but it was not until 2004 that a version of I, Robot was produced.

The most successful adaptation of a sci-fi author was Arthur C. Clarke with 2001 and its sequel. Reflecting the times, two earlier science fiction works by Ray Bradbury were adapted for cinema in the 1960s with Fahrenheit 451 and The Illustrated Man. Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughter-house Five was filmed in 1971 and Breakfast of Champions in 1998.

More recently Phillip K. Dick has become the most influential of sci-fi authors on science fiction film. His work manages to evoke the paranoia that has been a central feature of the genre without invoking alien influences. Films based on Dick's works include Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (1990), Minority Report (2002), and Paycheck (2003). These film versions are often only loose adaptations of the original story, being converted into an action-adventure film in the process.

References

- Welch Everman, Cult Science Fiction Films, Citadel Press, 1995, ISBN 0-8065-1602-X.

- Peter Guttmacher, Legendary Sci-Fi Movies, 1997, ISBN 1-56799-490-3.

- Phil Hardy, The Overlook Film Encyclopedia, Science Fiction. William Morrow and Company, New York, 1995, ISBN 0879516267.

- Richard S. Myers, S-F 2: A pictorial history of science fiction from 1975 to the present, 1984, Citadel Press, ISBN 0-8065-0875-2.

- Gregg Rickman, The Science Fiction Film Reader, 2004, ISBN 0879109947.

- Vivian Sobchack, Screening Space: The American Science Fiction Film. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998, ISBN 081352492X.

- Errol Vieth, Screening Science: Context, Text and Science in Fifties Science Fiction Film, Lanham, MD and London: Scarecrow Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8108-4023-5

External links

- The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film and Television - horror, science fiction, fantasy and animation

- Science Fiction films from the 50's to modern day reviewed and evaluated

- The Greatest Films: Science Fiction Films

- Worm's Sci Fi Haven: Science Fiction Films Discussion Forum.

Categories: Film genres

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: