This US

Postage Stamp celebrates the 3-D movie craze of

the 1950s.

This US

Postage Stamp celebrates the 3-D movie craze of

the 1950s.

In film, the term 3-D (or 3D) is used to describe any visual presentation system that attempts to maintain or recreate moving images of the third dimension, the illusion of depth as seen by the viewer.

The principle involves taking two images simultaneously, with two cameras positioned side by side, generally facing each other and filming at a 90 degree angle via mirrors, in perfect synchronization and with identical technical characteristics. When viewed in such a way that each eye sees its photographed counterpart, the viewer's visual cortex will interpret the pair of images as a single three-dimensional image.

Contents |

Techniques

There are several methods of projecting 3-D images.

Anaglyphic

Polarization

Alternate-frame sequencing

Pulfrich effect

In the context of many computer games, 3D computer graphics refer to being composed of objects in a virtual 3-D world, not that they can be viewed in 3-D. For a stereoscopic 3-D game, two pictures (one for each eye), are needed.

History

Early patents

The stereoscopic era of motion pictures begins in in the late 1890s when William Friese-Greene, British film pioneer files a patent for a 3-D movie process. In his patent, two films are projected side by side on screen. The viewer looked through a stereoscope to converge the two images. Because of the obtrusive mechanics behind this, theatrical use was not practical[1].

Frederic Eugine Ives patented his stereo camera rig in 1900. The camera had two lenses coupled together 1 3/4 inches apart[2].

In 1903, 3-D films were shown at the Paris Exposition under the auspicies of the Lumiere Brothers. While it is unconfirmed, the footage may have been a remake of their film, L'Arrivée du Train. Reguardless, they filmed this footage stereoscopically, later in the late 1930s[1].

Early systems of stereoscopic filmmaking (pre-1952)

The first confirmed 3-D feature was The Power of Love, which premiered at the Ambassador Hotel Theater in Los Angeles, CA on September 27, 1922. The camera rig was a product of its producer, Harry K. Fairall and cinematographer Robert F. Elder[1]. It was projected in dual-strip in the red/green anaglyph format, making it the first film in which anaglyph glasses were used. Whether Fairall used colored filters on the projection ports or whether he used tinted prints is unknown, but it is the first documented instance of dual-strip projection.

During the last few weeks in December of 1922, William Van Doren Kelley premiered the first in his series of "Plasticon" shorts entitled, Movies of the Future. Kelley was primarily a producer of color films, and his red and green, two-tone color system was used to print his anaglyph stereoscopic films. In early 1923, he premiered the second Plasticon, stereoscopic views of Washington D.C.. Both of these were shown at the Rivoli Theater in New York, NY.

A detail from an article about the Teleview

system, created by Hammond and Cassidy. Only one

feature was ever produced with the system.

A detail from an article about the Teleview

system, created by Hammond and Cassidy. Only one

feature was ever produced with the system.

During this period, Laurens Hammond and William F. Cassidy unveiled their "Teleview" system. Teleview was the earliest alternate-frame sequencing form of projection. Through the use of two interlocked projectors, alternating frames were projected at the same time in rapid succession. Synchronized viewers attached to the arm-rests of the seats in the theater open and closed at the same time. The only known theater to have installed this system was the Selwyn Theater in New York. Although several shorts were produced with this system, the only feature projected in it was Radio-Mania on December 27, 1922.

In 1923, Frederick Eugene Ives and Jacob Leventhal released their first stereoscopic film entitled, Plastigrams, which was released through Educational Pictures in the red/blue anaglyph format. Ives and Leventhal then went on to produce further stereoscopic shorts in 1925: Zowie (April 10), Luna-cy (May 18), A Runaway Taxi (December 17) and Ouch (December 17). All were red-blue anaglyph and all were released by Pathé Films as the "Stereoscopic Series".

In 1936, Leventhal and John Norling were hired based on their test footage to film MGM's Audioscopiks series. The prints were by Technicolor in the red/green anaglyph format, and were narrated by Pete Smith. The first film, Audioscopiks premiered January 11, 1936 and The New Audioscopiks premiered January 15, 1938. Audioscopiks was nominated for the Academy Award for Short Film - Novelty in 1936.

With the success of the two Audioscopiks films, MGM produced one more short in anaglyph 3-D, another Pete Smith Specialty called Third Dimensional Murder. Unlike its predecessors, this short was shot with a studio-built camera rig. Prints were by Technicolor in red/blue anaglyph. The short is notable for being the first live-action appearance of the Frankenstein Monster as conceived by Jack Pierce for Universal Studios outside of their company.

While many of these films were printed by color systems, it should be noted that none of them were actually in color, and the use of the color printing was only to achieve an anaglyph effect.

Introduction of Polaroid

While attending Harvard University in 1932, Edwin H. Land formulated sheet plastic that polarized light. While his original intention was to create a filter for reducing glare from car headlights, Land did not underestimate the usage of his newly dubbed Polaroid filters in stereoscopic presentations.

In January 1936, Land gave the first demonstration of Polaroid filters in conjunction with 3-D photography at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The reaction was enthustiastic, and he followed it up with an installation at the New York Museum of Science. It is unknown what film was run for audiences with this installation.

Using Polaroid filters meant an entirely new set-up, however. Two prints, each carrying either the right or left eye, had to be synced up in projection using an external motor. Furthermore, polarized light would not register on a matte white screen, and only a screen made of silver or reflective material would correctly reflect the separate images.

Later that year, the first polaroid 3-D feature, Nozze Vagabonde appeared in Italy. The first color polaroid 3-D feature, Zum Greifen Nah premiered in Germany the following year.

John Norling also shot In Tune With Tomorrow, the first 3-D film both shot in color and projected using polaroid filters in the US. This short premiered at the 1939 New York World's Fair and was created specifically for the Chrysler Motor Pavillion. In it, a full 1939 Chrysler Plymouth is magically put together, set to music. Originally in black in white, the film was so popular that it was re-shot in color for the following year at the fair, under the title New Dimensions. In 1953, it was reissued by RKO as Motor Rhythm.

Another early short that utilized the Polaroid 3-D process was 1940's Magic Movies: Thrills For You produced by the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. for the Golden Gate Exposition. It consisted of shots of various views that could be seen on Pensylvannia Railroad's trains.

The "golden era" (1952-1955)

What aficionados consider the "golden era" of 3-D began in 1952 with the release of the first color stereoscopic feature, Bwana Devil, produced, written and directed by Arch Oboler. The film was shot in Natural Vision, a process that was co-created and controlled by M.L. Gunzberg. Gunzberg, who built the rig with his brother, Julian, and two other associates, shopped it without success to various studios before Oboler used it for this feature, which went into production with the title, The Lions of Gulu. The film stars Robert Stack, Barbara Britton and Nigel Bruce.

As with practically all of the features made during this boom, Bwana Devil was projected dual-strip, with polaroid filters. During the 1950s, the familiar disposable, anaglyph glasses made of cardboard were mainly used for comic books, two shorts by Dan Sonny Productions, and three shorts produced by Lippert Productions. One should note, however, that even the Lippert shorts were available in the dual-strip format alternatively.

Because the features utilized two projectors, a capacity limit of film being loaded onto each projector (about 6000 feet) meant that an intermission was necessary for every movie. Quite often, intermission points were written into the script of the film at a major plot point.

During Christmas of 1952, producer Sol Lesser quickly premiered the dual-strip showcase called Stereo Techniques in Chicago. Lesser acquired the rights to five dual strip shorts. Two of them, Now is the Time (to Put On Your Glasses) and Around is Around, were produced for the National Film Board of Canada and the remaining three were produced in Britain for Festival of Britain by Raymond Spottiswoode. These were A Solid Explanation, Royal River, and The Black Swan.

James Mage was also an early pioneer in the 3-D craze. Using his 16mm 3-D Bolex system, he premiered his Triorama program on February 10, 1953 with his four shorts: Sunday In Stereo, Indian Summer, American Life, and This is Bolex Stereo. This show is considered lost

Another early 3-D film during the boom was the Lippert Productions short, A Day in the Country, narrated by Joe Besser and comprised of mostly test footage. Unlike all of the other Lippert shorts, which were available in both dual-strip and anaglyph, this production was released anaglyph only.

April of 1953 saw two groundbreaking features in 3-D: Columbia's Man In the Dark and Warner Bros. House of Wax, the first 3-D feature with stereophonic sound. House of Wax, outside of Cinerama, was the first time many American audiences heard recorded stereophonic sound. It was also the film that typecast Vincent Price as a horror star as well as the "King of 3-D" after becoming the actor to star in the most 3-D features (the others were The Mad Magician, Dangerous Mission, and Son of Sinbad). The success of these two films proved that major studios now had a method of getting moviegoers back into theaters and away from television sets, which were causing a steady decline in attendance.

The Walt Disney Studios waded into 3-D with its May 28, 1953 release of Melody, which accompanied the first 3-D western, Columbia's Fort Ti at its Los Angeles opening. It was later shown at Disneyland's Fantasyland Theater, and appears on the Fantasia 2000 DVD.

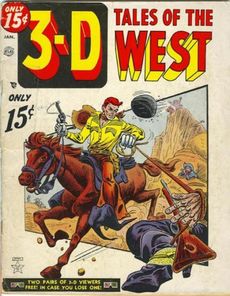

3-D Tales of the West (Atlas

Comics, Jan. 1954), one of the comic books

and other spin-offs of the '50s 3D craze.

3-D Tales of the West (Atlas

Comics, Jan. 1954), one of the comic books

and other spin-offs of the '50s 3D craze.

Universal-International released their first 3-D feature on May 27, 1953, It Came from Outer Space, with stereophonic sound. Following that was Paramount's first feature, Sangaree with Fernando Lamas and Arlene Dahl.

Columbia released two 3-D shorts with the Three Stooges in 1953: Spooks and Pardon My Backfire.

John Ireland, Joanne Dru and Macdonald Carey starred in the color Jack Broder production, Hannah Lee, which premiered June 19, 1953. The film was directed by Ireland, who sued Broder for his salary. Broder countersued, claiming that Ireland went over production costs with the film.

Another famous entry in the golden era of 3-D was the 3 Dimensional Pictures production of Robot Monster. The film was allegedly scribed in an hour by screenwriter Wyott Ordung and filmed in a period of two weeks on a shoestring budget. Despite these shortcomings and the fact that the crew had no previous experience with the newly-built camera rig, luck was on the cinematographer's side, as many find the 3-D photography in the film is well shot and aligned. Robot Monster also has a notable score by then up-and-coming composer, Leonard Bernstein. The film was released June 24, 1953 and went out with the short Stardust in Your Eyes, which starred nightclub comedian, Slick Slavin.

20th Century Fox produced their only 3-D feature, Inferno, starring Rhonda Fleming. Fleming, who also starred in Those Redheads from Seatte, and Jivaro, shares the spot for being the actress to appear in the most 3-D features with Patricia Medina, who starred in Sangaree, Phantom of the Rue Morgue and Drums of Tahiti. Darryl F. Zanuck expressed little interest in stereoscopic systems, and at that point was preparing to premiere the new film system, CinemaScope.

The first decline in the theatrical 3-D craze started in the late summer/early fall of 1953. The factors for this decline were:

- Two prints had to be projected simultaneously.

- The prints had to remain exactly alike after repair, or synchronization would be lost.

- It sometimes required two projectionists to keep sync working properly.

- When either prints or shutters became out of sync, the picture became virtually unwatchable and accounted for headaches and eye strain.

- The necessary silver projection screen was very directional and caused sideline seating to be unusable with both 3-D and regular films, due to the angular darkening of these screens. Later films that opened in wider-seated venues often premiered flat for that reason (such at Kiss Me Kate at the Radio City Music Hall).

Because projection booth operators were at many times careless, even at preview screenings of 3-D films, trade and newspaper critics claimed that certain films were "hard on the eyes."

Sol Lesser attempted to follow up Stereo Techniques with a new showcase, this time, five shorts that he himself produced. The project was to be called The 3-D Follies and was to be distributed by RKO. Unfortunately, because of financial difficulties and the growing disinterest in 3-D, Lesser cancelled the project during the summer of 1953, making it the first 3-D film to be aborted in production. Two of the three shorts were shot were Carmenesque, a burlesque dance number starring Lili St. Cyr and Fun in the Sun, a daytime sport short directed by famed set designer/director William Cameron Menzies, who also directed in the 3-D feature, The Maze for Allied Artists.

Although it was more expensive to install, the major competing realism process was anamorphic widescreen, first utilized by Fox with Cinemascope and its September premiere in The Robe. Anamorphic widescreen features needed only a single print, so synchronization was not an issue. Cinerama was also a competitor from the start and had better quality control than 3-D because it was owned by one company that focussed on quality control. However, most of the 3-D features past the summer of 1953 were released in the flat widescreen formats ranging from 1.66:1 to 1.85:1. It should be noted that early in studio advertisements and articles about widescreen and 3-D formats, widescreen systems were being referred to as "3-D," causing some confusion among scholars.

There was no single instance of combining Cinemascope with 3-D until 1960, with a film called September Storm, and even then, that was a blow-up from a non-anamorphic negative. September Storm also went out with the last dual-strip short, Space Attack, which was actually shot in 1954 under the title, The Adventures of Sam Space.

In December 1953, 3-D made a comeback, with the release of several important 3-D films, including MGM's musical Kiss Me, Kate. Kate was the hill on which 3-D had to pass over to survive. MGM tested it in six theaters: three in 3-D and three flat. The response towards the 3-D version was so well-received that the film quickly went into a wide stereoscopic release. Contrary to published opinion that stated the film played most theaters flat, the release was so popular that the demand for the 3-D version caused a surplus order of Technicolor dual-strip prints. The film, based on the popular Samuel and Bella Spewack musical, was one of MGM's "Lucky 7" films of the year, and starred the MGM songbird team of Howard Keel and Kathryn Grayson as the leads, supported by Ann Miller, Keenan Wynn, Bobby Van, James Whitmore, Kurt Kasznar and Tommy Rall. The film also prominently promoted its use of stereophonic sound.

Several other features that helped put 3-D back on the map that month were the John Wayne feature Hondo (distributed by Warner Bros.), Columbia's Miss Sadie Thompson with Rita Hayworth, and Paramount's Money From Home with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Paramount also released the cartoon shorts, Boo Moon with Casper, the Friendly Ghost and Popeye, Ace of Space with Popeye the Sailor.

Top Banana, based on the popular stage musical with Phil Silvers, was brought to the screen with the original cast. Although merely a filmed stage production, the idea was that every audience member would feel that they would have the best seat in the house through color photography and 3-D. Although the film was shot and edited in 3-D, United Artists, the distributor, felt the production was uneconomical in stereoscopic form and released the film flat on January 27, 1954. It remains one of two "Golden era" features, including another United Artists feature, Southwest Passage (with John Ireland and Joanne Dru), that are currently considered lost.

A string of successful 3-D movies followed the second wave. Some highlights are:

- The French Line, starring Jane Russell and Gilbert Roland, a Howard Hughes/RKO production. The film became infamous for being released without an MPAA seal of approval, after several suggestive lyrics were included, as well as one of Ms. Russell's particularly revealing costumes. Playing up her sex appeal, one tagline for the film was, "It'll knock both of your eyes out!" The film was later cut and approved by the MPAA for a general flat release, despite having a wide and profitable 3-D release.

- Taza, Son of Cochise, which starred Rock Hudson as the title role, Barbara Rush as the love interest, and Rex Reason (billed as Bart Roberts) as his renegade brother, released through Universal-International.

- Two ape films: Phantom of the Rue Morgue, featuring Karl Malden and Patricia Medina, and produced by Warner Bros. and based on Edgar Allan Poe's Murders in the Rue Morgue, and Gorilla At Large, a Panoramic Production starring Cameron Mitchell, distributed through Fox.

- Creature From The Black Lagoon, starring Richard Carlson and Julie Adams, directed by Jack Arnold. Arguably the most famous 3-D movie, and the only 3-D feature that spawned a sequel, Revenge of the Creature in 3-D (followed by another sequel, The Creature Walks Among Us, shot flat).

- Cat Women of the Moon, an Astor Picture starring Victor Jory and Marie Windsor. Leonard Bernstein composed the score.

- Dial M for Murder, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Ray Milland, Robert Cummings, and Grace Kelly, is considered by aficionados of 3-D to be have some of the best examples of the process. Ironically, only one, unconfirmed playdate is known for the film to have been shown in 3-D. The film's 3-D reputation came about in the 1970s, with several repertory screenings.

- Gog, an Ivan Tors production, dealing with realistic science fiction. The second film in Tors' "Office of Scientific Investigation" trilogy of film, which included, The Magnetic Monster and Riders to the Stars.

- The Diamond Wizard, the only stereoscopic feature shot in Britain, released flat in both the UK and US. It starred and was directed by Dennis O'Keefe.

- Son of Sinbad, another RKO/Howard Hughes production, starring Dale Robertson, Lili St. Cyr, and Vincent Price. The film was shelved after Hughes ran into difficulty with The French Line, and wasn't released until 1955, in which time it went out flat, converted to the SuperScope process.

3-D's final decline was in the late spring of 1954, for the same reasons as the previous lull, as well as the further success of widescreen formats with theater operators. Even though Polaroid had created a well-designed "Tell-Tale Filter Kit" for the purpose of recognizing and adjusting out of sync and phase 3-D, exhibitors still felt uncomfortable with the system and turned their focuses instead to processes such as CinemaScope. The last 3-D feature to be released in that format during the "Golden era" was Revenge of the Creature, on February 23, 1955. Ironically, the film had a wide release in 3-D and was well received at the Box Office.

Revival (1960-1979)

Stereoscopic films largely remained dormant for the first part of the 1960s, with those that were released usually being anaglyph exploitation films. One film of notoriety was the Beaver-Champion/Warner Bros. production, The Mask(1961). The film was shot in 2-D, but to enhance the bizarre qualities of the dream-world that is induced when the main character puts on a cursed tribal mask, the film went to anaglyph 3-D. These scenes were printed by Technicolor on their first run in red/green anaglyph.

Although 3-D films appeared sparsely during the ealy '60s, the true second wave of 3-D cinema was set into motion with the same producer who started the craze of the '50s. Using a new technology called Space-Vision 3D, stereoscopic films were printed with two images on top of one another in a single academy ratio frame on a single strip, and needed only one projector fitted with a special lens. This so-called "over and under" technique eliminated the need for dual projector set-ups, and produced widescreen polaroid 3-D images.

Arch Oboler once again had the vision for the system that no one else would touch, and put it to use on his film entitled The Bubble, which starred Michael Cole, Deborah Walley, and Johnny Desmond. Similar to Bwana Devil, the critics panned The Bubble, but audiences flocked to see it, and it became financially sound enough to promote the use of the system to other studios, particularly independents, who did not have the money for expensive dual-strip prints of their productions.

In 1970, Stereovision developed a different single-strip format, which printed two images squeezed side-by-side and used an anamorphic lens to widen the pictures through polaroid filters. Louis K. Sher (Sherpix) and Stereovision released the softcore sex comedy The Stewardesses (self-rated X, but later re-rated R by the MPAA). The film cost 100,000 USD to produce, but earned $27 million ($110 million in constant-2006 dollars) in fewer than 800 theaters, becoming the most profitable 3-Dimensional film to date. It was later released in 70mm 3-D. Some 36 films world-wide were made with Stereovision over 25 years, using either a widescreen (above-below) or the anamorphic (side by side) format or 70mm 3-D.

The quality of the following 3-D films were not much more inventive, as many were either softcore and even hardcore adult films, horror films, or a combination of both. Paul Morrisey's Flesh For Frankenstein (aka Andy Warhol's Frankenstein) was a superlative example of such a combination.

The revival's apex (1980-1984)

In the early 1980s, IMAX (Large format-sideways running, 70mm) began offering non-fiction films in 3-D, and fiction starting with the 45-minute Wings of Courage (1995), by director Jean-Jacques Annaud, about the author and pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

Using the over-under process pioneered by SpaceVision, Hollywood's film-makers hit a craze comparable to that of the one thirty years previously. With the popularity of StereoVision re-issues of House of Wax and Dial M For Murder, newly inspired directors jumped the bandwagon in creating 3-D films geared towards newer, mainstream audiences. Some of these included:

- Amityville 3-D

- Comin' At Ya! and Treasure of the Four Crowns

- Friday the 13th: Part III

- Jaws 3-D

- Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jarad Syn

- Parasite

- Silent Madness

3-D formats (1984-Present)

In 2003, James Cameron's "Ghosts of the Abyss" was released as the first full-length 3-D IMAX feature filmed with the Reality Camera System. This camera system used the latest HDTV video cameras, not film and was built for Cameron for his requirements. The same camera system was used to film "Spy Kids 3D: Game Over" (2003), "Aliens of the Deep" IMAX (2005) and "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl 3D" (2005).

In Nov. 2004, Polar Express was released as IMAX's full-length, animated 3-D feature. It was released in over 3550 theaters in 2D, and only 62 IMAX locations. The return from those few 3-D theaters was about 25% of the total. The 3-D version earned about 14 times as much per screen than the 2D version. This has prompted a greatly intensified interest in 3-D and 3-D presentation of animated films.

In November 2005, Walt Disney Studio Entertainment released Chicken Little, in the new digital 3-D format known as REAL D, utilizing one digital projector alternating clockwise and counterclockwise polarized images at 144 frames per second. Glasses are worn that diffuse each circular polarization for one of the eyes so that a 3-D effect is achieved. The use of circular polarization improves on the older technique of linear polarization in that there is no ghosting or leakage. Following the successful financial gross of the film, further animation films in 3-D have been announced as in production and to be ready by December 2006 in both the IMAX 3-D film format as well as Digital 3-D. Disney also announced that they hope to have 750 Digital 3-D installations in place for their fall 2006 3-D release, Meet the Robinsons.

The 3D technology currently used worldwide is based on the methods and inventions of Félix Bodrossy, who did not patent his methods, as these are still considered the most up-to-date. (Source in Hungarian, reference in Dutch)

The World 3-D Exposition

In September of 2003, Sabucat Productions organized the first World 3-D Exposition, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the original craze. The Expo was held at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre. During the two-week festival, over 30 of the 50 "golden era" stereoscopic features (as well as shorts) were screened, many coming from the collection of film historian and archivist Robert Furmanek, who had spent the previous 15 years pain-stakingly tracking down and preserving each film to its original glory. In attendance were many stars from each film, respectively, and some were moved to tears by the sold-out seating with audiences of film buffs from all over the world who came to remember their previous glories.

In May of 2006, the second World 3-D Exposition was announced for September of that year. Along with the favorites of the previous exposition were newly discovered features and shorts, and like the previous Expo, guests from each film. Expo II was announced as being the local for the world premiere of several films never before seen in 3-D, including The Diamond Wizard and the Universal short, Hawaiian Nights with Mamie Van Doren and Pinkie Lee. Other "re-premieres" of films not seen since their original release in stereoscopic form included Cease Fire!, Taza, Son of Cochise, Wings of the Hawk, and Those Redheads From Seattle.

New developments (2006)

New technologies are coming that will allow current 2-D films to be remastered into 3-D using proprietary procedures. George Lucas has announced that he will re-release his Star Wars films in 3-D based on a conversion process from the company In-Three.

James Cameron (Titanic) will shoot his new film Battle Angel in digital 3-D. Filming will use HDTV cameras and the Fusion Camera system.

Animated films Open Season, Monster House, The Ant Bully and Happy Feet, scheduled for upcoming release, will be released in either digital in a few hundred theaters along with a 2D release or in IMAX 3D along with regular 2D 35mm.

Both digital and IMAX are quite costly ways of showing 3D. Another approach being proposed is the upgrading of existing 35mm to show 3D with a six perf pull-down in the projector. Advocates of this, CINE 160 3D, point to 10 to 1 cost savings and proven results with film. (The film image is 1.6 times the conventional frame size.)

In late 2005 Steven Spielberg told the press he was involved in patenting a 3-D cinema system that does not need glasses, and is based on plasma screens. A computer splits each film-frame, and then projects the two split images onto the screen at differing angles, to be picked up by tiny angled ridges on the screen. (Spielberg is co-producer of the film "Monster House".)

Even episodic TV series are embracing 3-D, as an episode of NBCs Medium hit the home HD screens in anaglyph 3-D on November 21, 2005.

In 2005 Super78 Studios Nominated for a VES award for it's 3D film Curse Of Darkastle.

Notes

- ^ a b c Limbacher, James L. Four Aspects of the Film. 1968.

- ^ Norling, John A. "Basic Principles of 3-D Photography and Projection" New Screen Techniques, P. 48

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: