In medicine and biology, a receptor antagonist is a ligand that inhibits the function of an agonist and inverse agonist for a specific receptor.

Most drugs exert effects, both beneficial and detrimental, by interacting with specific receptors that are present on or within cells. Historically, receptors were thought to act much like light switches. Agonists were thought to turn "on" a single cellular response by binding to the receptor, thus initiating a biochemical mechanism for change within a cell. Antagonists were thought to turn "off" that response by 'blocking' the receptor from the agonist.

Recently, the discovery of inverse agonists and other concepts such as functional selectivity have blurred these definitions.

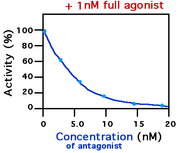

Today's current theories involving receptor antagonists center around an antagonist's ability to counteract the effects of agonists and inverse agonists (if one exists for the specific receptor). Antagonists work by binding to receptors and stopping cascades put in place by an agonist. On their own, antagonists produce no effect by themselves to a cell, and are said to have zero intrinsic activity and zero efficacy.

There are three kinds of receptor antagonists:

- Antagonists that compete with an agonist for a binding site are competitive antagonists. They bind to the same receptor binding site as the agonist, thus competing for the same binding site. An example is the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, IL-1Ra. High concentrations of agonist will displace the antagonist from the receptor.

- Antagonists that antagonize by other means are non-competitive antagonists. They bind to a different binding-site from the agonists, exerting their action to that receptor via the other binding site. Thus, they are called non-competitive antagonists because they do not compete for the same binding site as the agonists.

- Antagonists that bind covalently with the receptor binging site are irreversible antagonists. Unlike competitive antagonism, the covalent nature of the bond means the antagonist cannot be displaced by raising the concentration of the agonist.

Antagonists may be naturally occurring as is the case with physiological antagonists, or they may be synthetic and made to mimic the body's physiological antagonists. There are multiple antagonists for most receptors. A synthetic antagonist may compete with a physiological antagonist for binding sites upon receptors. Similarly, endogenous antagonists may also compete with one another. The antagonist which is bound is usually the one with the higher affinity for the receptor.

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: