|

|

|

|

|

Quinine

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

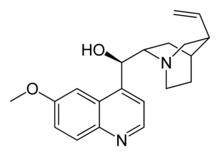

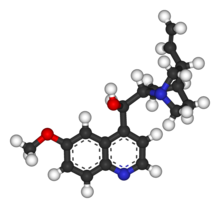

| (2-ethenyl-4-azabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-5-yl)- (6-methoxyquinolin-4-yl)-methanol | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 130-95-0 |

| ATC code | M09AA01 P01BC01 |

| PubChem | 8549 |

| DrugBank | APRD00563 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C20H24N2O2 |

| Mol. weight | 324.417 g/mol |

| Physical data | |

| Melt. point | 177 °C (351 °F) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 76 to 88% |

| Protein binding | ~70% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (mostly CYP3A4 and CYP2C19-mediated) |

| Half life | ~18 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (20%) |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | X (U.S.), D (Au) |

| Routes | Oral |

Quinine is a natural white crystalline alkaloid having antipyretic, anti-malarial with analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties and a bitter taste. It is a stereoisomer of quinidine.

Quinine was previously superseded by chloroquine, but is now again the drug of choice for treatment of falciparum malaria because of the rise of chloroquine resistance. Quinine is available with a prescription in the U.S.. Quinine is also used to treat nocturnal leg cramps and arthritis and it has also been used (with limited success) to treat people who had been infected by prions. It was once a popular heroin adulterant.

Contents |

Mechanism of action

The theorized mechanism of action for quinine and related anti-malarial drugs is that these drugs are toxic to the malaria parasite, specifically by interfering with the parasite's ability to break down and digest hemoglobin, thus starving the parasite and/or causing the build-up of toxic levels of partially degraded hemoglobin in the parasite.

Sources of quinine

Quinine was extracted from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, isolated and named in 1820 by French researchers Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou. The name was derived from the original Quechua (Native American) word for the cinchona tree bark, "Quina" or "Quina-Quina", which roughly means "bark of bark" or "holly bark". Prior to 1820, the bark was first dried, ground to a fine powder, and then mixed into a liquid (commonly wine) before being drunk.

The large scale use of quinine as a prophylactic started around 1850, although it had been used in un-extracted form by Europeans since at least the early 1600s. Quinine was first used to treat malaria in Rome in 1631. During the 1600s, malaria was endemic to the swamps and marshes surrounding the city of Rome. Over time, malaria was responsible for the death of several Popes, many Cardinals, and countless common citizens of Rome. Most of the priests trained in Rome had seen malaria victims, and were familiar with the shivering brought on by the cold phase of the disease. In addition to its anti-malarial properties, quinine is an effective muscle relaxant, long used by the Quechua Indians of Peru to halt shivering brought on by cold temperatures. The Jesuit priest Agostino Salumbrino, an apothecary by training who lived in Lima, observed the Quechua using the quinine-containing bark of the cinchoa tree for that purpose. While its effect in treating malaria (and hence malaria-induced shivering) was entirely unrelated to its effect in controlling shivering from cold, it was still the correct medicine for malaria. At the first opportunity, he sent a small quantity to Rome to test in treating malaria. In the years that followed, cinchona bark became one of the most valuable commodities shipped from Peru to Europe.

Cinchona trees remain the only practical source of quinine. However, under wartime pressure, research towards its artificial production was undertaken. A formal chemical synthesis was accomplished in 1944 by R.B. Woodward and W.E. Doering, American chemists. Since then, several more efficient total syntheses have been achieved (see review article in Angewandte Chemie, Int. Ed., 2005, 44, p. 854 ff), but none of them can compete in economic terms with isolation of the alkaloid from natural sources.

Dosing

Quinine is an extremely basic compound and is therefore always presented as a salt. Various preparations that exist include the hydrochloride, dihydrochloride, sulphate, bisulphate, and gluconate. This makes quinine dosing very complicated, because each of the different salts has a different weight:

- quinine base 100mg, is equivalent to

- quinine bisulphate 169mg, is equivalent to

- quinine dihydrochloride 122 mg, is equivalent to

- quinine hydrochloride 122 mg, is equivalent to

- quinine sulphate 121 mg, is equivalent to

- quinine gluconate 160mg.

All quinine salts may be given orally or intravenously (IV); quinine gluconate may also be given intramuscularly (IM) or rectally (PR). [1][2] The main problem with the rectal route is that the dose can be expelled before it is completely absorbed, but this can be rectified by giving half dose again.

The IV dose of quinine is 8mg/kg of quinine base every eight hours; the IM dose is 12.8mg/kg of quinine base twice daily; the PR dose is 20mg/kg of quinine base twice daily. Treatment should be given for seven days.

The preparations available in the UK are quinine sulphate (200mg or 300mg tablets) and quinine hydrochloride (300mg/ml for injection). Quinine is not licensed for IM or PR use in the UK. The adult dose in the UK is 600mg quinine dihydrochloride IV or 600mg quinine sulphate PO every eight hours.

In the US, quinine sulphate is available as 324mg tablets; the adult dose is two tablets every eight hours. There is no injectable preparation of quinine licensed in the US: quinidine is used instead;[3][4].

Side effects

It is usual for quinine in therapeutic doses to cause cinchonism; in rare cases, it may even cause death (usually by pulmonary edema). The development of mild cinchonism is not a reason for stopping or interrupting quinine therapy and the patient should be reassured. Blood glucose levels and electrolyte concentrations must be monitored when quinine is given by injection; the patient should also ideally be in cardiac monitoring when the first quinine injection is given (these precautions are often unavailable in developing countries where malaria is most a problem).

Cinchonism is much less common when quinine is given by mouth, however, oral quinine is not well tolerated (quinine is exceedingly bitter and many patients will vomit up quinine tablets): other drugs such as Fansidar® (sulfadoxine with pyrimethamine) or Malarone® (proguanil with atovaquone) are often used when oral therapy is required. Blood glucose, electrolyte and cardiac monitoring are not necessary when quinine is given by mouth.

Quinine can cause paralysis if accidentally injected into a nerve.

Quinine is extremely toxic in overdose and the advice of a poisons specialist should be sought immediately.

Quinine and pregnancy

In very large doses, quinine also acts as an abortifacient; in the U.S., quinine is classed as a Category X teratogen by the Food and Drug Administration, meaning that it can cause birth defects (especially deafness) if taken by a woman during pregnancy. In the UK, the recommendation is that pregnancy is not a contra-indication to quinine therapy for falciparum malaria (which directly contradicts the US recommendation), although it should be used with caution; the reason for this is that the risks to the pregnancy are small and theoretical, as opposed to the very real risk of death from falciparum malaria.

Quinine and interactions with other diseases

Quinine can cause haemolysis in G6PD deficiency, but again, this risk is small and the physician should not hesitate to use quinine in patients with G6PD deficiency when there is no alternative available. Quinine can also cause drug-induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), with quinine being the culprit.

Quinine can cause abnormal heart rhythms and should be avoided if possible in patients with atrial fibrillation, conduction defects or heart block.

Quinine must not be used in patients with haemoglobinuria, myasthenia gravis or optic neuritis, because it worsens these conditions.

Non-medical uses of quinine

Quinine is a flavour component of tonic water and bitter lemon. According to tradition, the bitter taste of anti-malarial quinine tonic led British colonials in India to mix it with gin, thus creating the gin and tonic cocktail, which is still popular today in both India and Great Britain, and in other former British colonies.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration limits tonic water quinine to 83 ppm, which is one-half to one-quarter the concentration used in therapeutic tonic.

In France, quinine is an ingredient of an apéritif known as Quinquina.

Quinine is often added to street drugs cocaine or ketamine in order to "cut" the product and make more profit.

Because of its relatively constant and well-known fluorescence quantum yield, quinine is also used in photochemistry as a common fluorescence standard.

In Canada, quinine is an ingredient in the carbonated chinotto beverage called Brio.

In the UK, quinine is an ingredient in the carbonated and caffienated beverage, Irn-Bru.

References

- ^ Barennes H, et al. (1996). "Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of a new intrarectal quinine formulation in children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria". Brit J Clin Pharmacol 41 (5): 389. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.03246.x.

- ^ "Safety and efficacy of rectal compared with intramuscular quinine for the early treatment of moderately sever malaria in children: randomised clinical trial". Brit Med J 332 (7549): 1055–57.

- ^ Center for Disease Control (1991). "Treatment with Quinidine Gluconate of Persons with Severe Plasmodium falciparum Infection: Discontinuation of Parenteral Quinine". Morb Mort Weekly Rep 40 (RR-4): 21–23. Retrieved on 2006-05-06.

- ^ Magill A, Panosian C (2005). "Making Antimalarial Agents Available in the United States". New Engl J Med 353 (4): 335–337.

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: