|

|

|

|

|

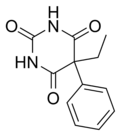

Phenobarbital

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 5-ethyl-5-phenyl-1,3-diazinane-2,4,6-trione | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 50-06-6 |

| ATC code | N05CA24 N03AA02 |

| PubChem | 4763 |

| DrugBank | APRD00184 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C12H12N2O3 |

| Mol. weight | 232.235 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Protein binding | 20 to 45% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (mostly CYP2C19) |

| Half life | 53 to 118 hours |

| Excretion | Renal and fecal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | D(US) |

| Legal status | Class B(UK) Schedule IV(US) |

| Routes | Oral, rectal, parenteral (intramuscular and intravenous) |

Phenobarbital (INN) or phenobarbitone (former BAN) is a barbiturate, first marketed as Luminal® by Farbwerke Fr. Bayer and Co. It is the most widely used anticonvulsant worldwide and the oldest still in use. It also has sedative and hypnotic properties but, as with other barbiturates, has been superseded by the benzodiazepines for these indications. The World Health Organization recommends its use as first-line for partial and generalized tonic–clonic seizures in developing countries. It is a core medicine in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, which is a list of minimum medical needs for a basic health care system.[1] In more affluent countries, it is no longer recommended as a first or second-line choice anticonvulsant for most seizure types,[2][3] though it is still commonly used to treat neonatal seizures.[4]

Contents |

History

The first barbiturate drug, barbital, was synthesized in 1902 by German chemists Emil Fischer and Joseph von Mering at Bayer. By 1904 several related drugs, including phenobarbital, had been synthesized by Fischer. Phenobarbital was brought to market in 1912 by the drug company Bayer using the brand Luminal. It remained a commonly prescribed sedative and hypnotic until the introduction of benzodiazepines in the 1950s.[5]

Phenobarbital's soporific, sedative and hypnotic properties were well known in 1912, but nobody knew it was also an effective anticonvulsant. The young doctor Alfred Hauptmann gave it to his epilepsy patients as a tranquiliser and discovered that their epileptic attacks were susceptible to the drug. Hauptmann performed a careful study of his patients over an extended period. Most of these patients were using the only effective drug then available, bromide, which had terrible side effects and limited efficacy. On phenobarbital, their epilepsy was much improved: the worse patients suffered fewer and lighter seizures and some patients became seizure free. In addition, they improved physically and mentally as bromides were removed from their regime. Patients who had been institutionalised due to the severity of their epilepsy were able to leave and, in some cases, resume employment. Hauptman dismissed concerns that its effectiveness in stalling epileptic attacks could lead to patients suffering a build-up that needed to be "discharged". As he expected, withdrawal of the drug lead to an increase in seizure frequency – it was not a cure. The drug was quickly adopted as the first widely effective anticonvulsant, though World War I delayed its introduction in the U.S.[6]

Phenobarbital was used to treat neonatal jaundice by increasing liver metabolism and thus lowering bilirubin levels. In the 1950s, phototherapy was discovered, and became the standard treatment.[7]

In 1940, Winthrop Chemical produced sulfathiazole tablets that were contaminated with phenobarbital. This occurred because both tablets were produced side-by-side and equipment could be interchanged. Each antibacterial tablet contained more than twice the required dose of phenobarbital necessary to induce sleep. Hundreds of patients died or were injured as a result. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration investigation was highly critical of Winthrop and the scandal lead to the introduction of Good Manufacturing Practice for drugs.[7]

Phenobarbital was used for over 25 years as prophylaxis in the treatment of febrile seizures.[8] Although an effective treatment in preventing recurrent febrile seizures, it had no positive effect on patient outcome or risk of developing epilepsy. The treatment of simple febrile seizures with anticonvulsant prophylaxis is no longer recommended.[9][10]

Indications

Phenobarbital is indicated in the treatment of all types of seizures except absence seizures.[2][11] Phenobarbital is no less effective at seizure control than more modern drugs such as phenytoin and carbamazepine. It is, however, significantly less well tolerated.[12][13]

The first line drugs for treatment of status epilepticus are fast acting benzodiazepines such as diazepam or lorazepam. If these fail then phenytoin may be used, with phenobarbital being an alterntive in the US but used only third line in the UK.[14] Failing that, the only treatment is anaesthesia in intensive care.[11][15]

Phenobarbital is the first line choice for the treatment of neonatal seizures.[4][16][17] Concerns that neonatal seizures in themselves could be harmful make most physicians treat them aggressively. There is, however, no reliable evidence to support this approach.[18]

Side effects

Sedation and hypnosis are the principal side effects of this drug. CNs effects like dizziness, nystagmus and ataxia are also common. In old aged patients, they cause excitement and confusion while in children, they cause paradoxical hyperreactivity.

Interactions

Contraindications

Acute intermittent porphyria, oversensitivity for barbiturates, prior dependence on barbiturates, severe respiratory insufficiency and hyperkinesia in children.

Overdose

| ICD-10 | T42.3 |

|---|---|

| eMedicine | med/207 |

Phenobarbital causes a "depression" of the body's systems, mainly the central and peripheral nervous systems; thus, the main characteristic of phenobarbital overdose is a "slowing" of bodily functions, including decreased consciousness (even coma), bradycardia, bradypnea, hypothermia, and hypotension (in massive overdoses). Overdose may also lead to pulmonary edema and acute renal failure as a result of shock.

The electroencephalogram of a person with phenobarbital overdose may show a marked decrease in electrical activity, to the point of mimicking brain death. This is due to profound depression of the central nervous system, and is usually reversible.[19]

Treatment of phenobarbital overdose is supportive, and consists mainly in the maintenance of airway patency (through endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation), correction of bradycardia and hypotension (with intravenous fluids and vasopressors, if necessary) and removal of as much drug as possible from the body. Depending on how much time has elapsed since ingestion of the drug, this may be accomplished through gastric lavage (stomach pumping) or use of activated charcoal. Hemodialysis is effective in removing phenobarbital from the body, and may reduce its half-life by up to 90%.[19] There is no specific antidote for barbiturate poisoning.

Pharmacokinetics

Phenobarbital has an oral bioavailability of approximately 90%. Peak plasma concentrations are reached 8 to 12 hours after oral administration. It is one of the longest-acting barbiturates available – it remains in the body for a very long time (half-life of 2 to 7 days) and has very low protein binding (20 to 45%). Phenobarbital is metabolized by the liver, mainly through hydroxylation and glucuronidation, and induces most isozymes of the cytochrome P450 system. It is excreted primarily by the kidneys.

Veterinary uses

Phenobarbital is one of the initial drugs of choice to treat epilepsy in dogs, and is the initial drug of choice to treat epilepsy in cats.[20]

It may also be used to treat seizures in horses when benzodiazepine treatment has failed or is contraindicated.[21]

References

- Ole Daniel Enersen. Alfred Hauptmann.

- Kwan P, Brodie M (2004). "Phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in the 21st century: a critical review.". Epilepsia 45 (9): 1141-9. PMID 15329080.

Heaven's Gate

The Heaven's Gate cult members committed mass suicide in 1997 with phenobarbital mixed with vodka.

Footnotes

- ^ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (PDF). World Health Organization (March 2005). Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ^ a b NICE (2005-10-27). CG20 Epilepsy in adults and children: NICE guideline. NHS. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ Phenobarbital. Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved on 2006-09-07.

- ^ a b British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group (2006). “4.8.1 Control of epilepsy”, British National Formulary for Children, 255-6. ISBN 1747-5503.

- ^ Sneader, Walter (2005-06-23). Drug Discovery. John Wiley and Sons, 369. ISBN 0-4718-9979-8. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ Scott,, Donald F (1993-02-15). The History of Epileptic Therapy. Taylor & Francis, 59-65. ISBN 1-8507-0391-4. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ a b Rachel Sheremeta Pepling (06 2005). "Phenobarbital". Chemical and Engineering News 83 (25). Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ John M. Pellock, W. Edwin Dodson, Blaise F. D. Bourgeois (2001-01-01). Pediatric Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing, 169. ISBN 1-8887-9930-7. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ Robert Baumann (2005-02-14). Febrile Seizures. eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ various (March 2005). Diagnosis and management of epilepsies in children and young people pp. 15. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Retrieved on 2006-09-07.

- ^ a b British National Formulary 51

- ^ Taylor S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson PR, Marson AG (2003). "Phenobarbitone versus phenytoin monotherapy for partial onset seizures and generalized onset tonic-clonic seizures.". Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (2). DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002217. PMID 11687150. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ Tudur Smith C, Marson AG, Williamson PR (2003). "Carbamazepine versus phenobarbitone monotherapy for epilepsy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1). DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001904. PMID 12535420. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group (2006). “4.8.2 Drugs used in status epilepticus”, British National Formulary for Children, 269. ISBN 1747-5503.

- ^ Kälviäinen R, Eriksson K, Parviainen I (2005). "Refractory generalised convulsive status epilepticus : a guide to treatment.". CNS Drugs 19 (9): 759-68. PMID 16142991.

- ^ John M. Pellock, W. Edwin Dodson, Blaise F. D. Bourgeois (2001-01-01). Pediatric Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing, 152. ISBN 1-8887-9930-7. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ Raj D Sheth (2005-03-30). Neonatal Seizures. eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ Booth D, Evans DJ (2004). "Anticonvulsants for neonates with seizures". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3). DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004218.pub2. PMID 15495087. Retrieved on 2006-09-06.

- ^ a b Rania Habal (2006-01-27). Barbiturate Toxicity. eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved on 2006-09-14.

- ^ Thomas, WB (2003). Seizures and narcolepsy. In: Dewey, Curtis W. (ed.) A Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Press. ISBN 0813812496.

- ^ (February 8, 2005) Kahn, Cynthia M., Line, Scott, Aiello, Susan E. (ed.) The Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th ed., John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0911910506.

216.73.216.103

216.73.216.103 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: