|

Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill (COCP)

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Background | |

| B.C. type | Hormonal |

| First use | 1960 |

| Failure rates (per year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.1% |

| Typical use | 2.15 - 8.0% |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect | 1-4days |

| Reversibility | Yes |

| User reminders | Taken within same 12hour window each day |

| Clinic review | 6 months |

| Advantages | |

| Periods | Regulates, and often lighter and less painful |

| Benefits | Reduced ovarian and

endometrial cancer risk. May treat acne, PCOS, endometriosis |

| Disadvantages | |

| STD protection | No |

| Weight gain | Possible |

| Risks | Incr. DVTs, strokes, breast cancer |

| Medical notes | |

| Affected by broad-spectrum antibiotics, the herb Hypericum (St.Johns Wort) and some anti-epileptics, also vomiting or diarrhoea. Caution if history migraines. | |

Oral contraceptives, often referred to as "the Pill", are chemicals taken by mouth to inhibit normal fertility. All act on the hormonal system. Oral contraceptives have been on the market since 1960, and enjoy great popularity. They are used by millions of women around the world, but usage prevalence varies: one quarter of reproductive age women in the United Kingdom take the pill,[1] but only 1% of women in Japan.[2] Male oral contraceptives remain a subject of research and development.

Contents |

History

By the 1930s, scientists had isolated and determined the structure of the steroid hormones and found that high doses of androgens, estrogens or progesterone inhibited ovulation, but obtaining them from European pharmaceutical companies produced from animal extracts was extraordinarily expensive.

In 1939, Russell Marker, a professor of organic chemistry at Pennsylvania State University, developed a method of synthesizing progesterone from plant steroid sapogenins, initially using sarsapogenin from sarsaparilla which proved too expensive. After three years of extensive botanical research he discovered a much better starting material, diosgenin from inedible Mexican wild yams found in the jungles of Veracruz near Orizaba. Unable to interest his research sponsor Parke-Davis in the commercial potential of synthesizing progesterone from Mexican yams, Marker left Penn State and in 1944 co-founded Syntex with two partners in Mexico City before leaving Syntex a year later. Syntex broke the monopoly of European pharmaceutical companies on steroid hormones, reducing the price of progesterone almost 200-fold over the next eight years.[3]

Midway through 20th century, the stage was set for the development of a hormonal contraceptive, but pharmaceutical companies, universities and governments showed no interest in pursuing research.

In early 1951, reproductive physiologist Gregory Pincus, a leader in hormone research and co-founder of the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology (WFEB) in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, first met American birth control movement founder Margaret Sanger at a Manhattan dinner hosted by Abraham Stone, medical director and vice president of Planned Parenthood (PPFA), who helped Pincus obtain a small grant from PPFA to begin hormonal contraceptive research. Research started on April 25, 1951 with reproductive physiologist Min Chueh Chang repeating and extending the 1937 experiments of Makepeace et al. that showed injections of progesterone suppressed ovulation in rabbits. In October 1951, G. D. Searle & Company refused Pincus' request to fund his hormonal contraceptive research, but retained him as a consultant and continued to provide chemical compounds to evaluate.

In March 1952, Sanger wrote a brief note mentioning Pincus' research to her longtime friend and supporter, suffragist and philanthropist Katharine Dexter McCormick, who visited the WFEB and its co-founder and old friend Hudson Hoagland in June 1952 to learn about contraceptive research there. Frustrated when research stalled from PPFA's lack of interest and meager funding, McCormick arranged a meeting at the WFEB on June 6, 1953 with Sanger and Hoagland where she first met Pincus who committed to dramatically expand and accelerate research with McCormick providing fifty times PPFA's previous funding.

Pincus and McCormick enlisted Harvard clinical professor of gynecology John Rock, an expert in the treatment of infertility, to lead clinical research with women. At a scientific conference in 1952, Pincus and Rock, who had known each other for many years, discovered they were using similar approaches to achieve opposite goals. In 1952, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudo-pregnancy" state in eighty of his infertility patients with continuous gradually increasing oral doses of estrogen (diethylstilbestrol 5–30 mg/day) and progesterone (50–300 mg/day) and within the following four months an encouraging 15% became pregnant.

In 1953, at Pincus' suggestion, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudo-pregnancy" state in twenty-seven of his infertility patients with an oral 300 mg/day progesterone-only regimen for 20 days from cycle days 5–24 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding. This produced the same encouraging 15% pregnancy rate during the following four months without the troubling amenorrhea of the previous continuous estrogen and progesterone regimen. But 20% of the women experienced breakthrough bleeding and in the first cycle ovulation was suppressed in only 85% of the women, indicating that even higher and more expensive oral doses of progesterone would be needed to initially consistently suppress ovulation.

Pincus asked his contacts at pharmaceutical companies to send him chemical compounds with progestogenic activity. Chang screened over 200 chemical compounds in animals and found the three most promising were Syntex's norethindrone and Searle's norethynodrel and norethandrolone.

Chemists Carl Djerassi, Luis E. Miramontes and George Rosenkranz at Syntex in Mexico City had synthesized the first orally highly active progestin norethindrone in 1951.[4] Chemist Frank B. Colton at Searle in Skokie, Illinois had synthesized the orally highly active progestins norethynodrel (an isomer of norethindrone) in 1952 and norethandrolone in 1953.

In December 1954, Rock began the first tests of the ovulation-suppressing potential of 5–50 mg doses of the three oral progestins for three months (for 21 days per cycle—days 5–25 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding) in fifty of his infertility patients in Brookline, Massachusetts. 5 mg doses of norethindrone or norethynodrel and all doses of norethandrolone suppressed ovulation but caused breakthrough bleeding, but 10 mg and higher doses of norethindrone or norethynodrel suppressed ovulation without breakthrough bleeding and led to a 14% pregnancy rate in the following five months. Pincus and Rock selected Searle's norethynodrel for the first contraceptive trials in women citing its total lack of androgenicity versus Syntex's norethindrone's very slight androgenicity in animal tests.

Norethynodrel (and norethindrone) were subsequently discovered to be contaminated with a small percentage of the estrogen mestranol (an intermediate in their synthesis), with the norethynodrel in Rock's 1954-5 study containing 4-7% mestranol. When further purifying norethynodrel to contain less than 1% mestranol led to breakthrough bleeding, it was decided to intentionally incorporate 2.2% mestranol, a percentage that was not associated with breakthrough bleeding, in the first contraceptive trials in women in 1956. The norethynodrel and mestranol combination was given the proprietary name Enovid.

The first contraceptive trial of Enovid led by Edris Rice-Wray Carson began in April 1956 in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico. A second contraceptive trial of Enovid (and norethindrone) led by Edward T. Tyler began in June 1956 in Los Angeles. On January 23, 1957, Searle held a symposium reviewing gynecologic and contraceptive research on Enovid through 1956 and concluded Enovid's estrogen content could be reduced by 50% to lower the incidence of estrogenic gastrointestinal side effects without significantly increasing the incidence of breakthrough bleeding.

In June 1957, the FDA approved Enovid 10 mg (9.85 mg norethynodrel and 150 µg mestranol) for menstrual disorders based on data from its use by more than 600 women. Numerous additional contraceptive trials showed Enovid at 10, 5, and 2.5 mg doses to be highly effective. On July 23, 1959, Searle filed a supplemental application to add contraception as an approved indication for 10, 5 and 2.5 mg doses of Enovid. The FDA refused to consider the application until Searle agreed to withdraw the lower dosage forms from the application. On May 9, 1960, the FDA announced it would approve Enovid 10 mg for contraceptive use, which it did on June 23, 1960, by which time Enovid 10 mg had been in general use for three years during which time, by conservative estimate, at least half a million women had used it.

Although FDA approved for contraceptive use, Searle never marketed Enovid 10 mg as a contraceptive. Nine months later, in February 1961, the FDA approved Enovid 5 mg for contraceptive use. In July 1961, Searle finally began marketing Enovid 5 mg (5 mg norethynodrel and 75 µg mestranol) to physicians as a contraceptive.

Although the FDA approved the first oral contraceptive in 1960, contraceptives were not available to married women in all states until Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965 and were not available to unmarried women in all states until Eisenstadt v. Baird in 1972.

The first published case report of a blood clot and pulmonary embolism in a woman using Enovid did not appear until November 1961, four years after its approval, by which time it had been used by over one million women. It would take almost a decade of epidemiological studies to conclusively establish an increased risk of venous thrombosis in oral contraceptive users and an increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction in oral contraceptive users who smoke or have high blood pressure or other cardiovascular or cerebrovascular risk factors. These risks of oral contraceptives were dramatized in the 1969 book A Doctor's Case Against the Pill by feminist journalist Barbara Seaman who helped arrange the 1970 Senate hearings called by Senator Gaylord Nelson. The hearings were conducted by Senators who were all men and the witnesses in the first round of hearings were all men, leading Alice Wolfson and other feminists to protest the hearings and generate media attention. Their work led to mandating the inclusion of patient package inserts with oral contraceptives to explain their possible side effects and risks to help facilitate informed consent.[5] Today's standard dose oral contraceptives contain an estrogen dose that is one third lower than the first marketed oral contraceptive and contain lower doses of different, more potent progestins in a variety of formulations.

France

In 1967, the Neuwirth Law legalized contraception in France, including the pill. [6] The pill is the most popular form of contraception in France, especially among young women. The abortion rate has remained stable since the introduction of the pill. [7]

Japan

In Japan, lobbying from the Japan Medical Association prevented the Pill from being approved for nearly 40 years. Two main objections raised by the association were safety concerns over long-term use of the Pill, and concerns that the Pill use would lead to diminished use of condoms and thereby potentially increase sexually transmitted infection (STIs) rates.[8] Some voiced suspicions that potential loss of income due to lower abortion rates that could result from Pill use might have been a factor in the organization's objection. The association responded to its critics by pointing out that doctors would have received higher monetary compensation from prescribing pills, given Japan's national health insurance system. As of 2004, condoms accounted for 80% of birth control use in Japan, and this may explain Japan's comparably low rates of AIDS.[9]

The Pill was finally approved for use in 1999; however, the Pill prescription guidelines the government endorsed are quite stringent. They require Pill users to visit a doctor every three months for pelvic examinations and undergo tests for sexually transmitted diseases and uterine cancer. In the United States and Europe, in contrast, an annual or bi-annual clinic visit is standard for Pill users. As a possible result of the stringent regulations, very few women in Japan use the Pill.[2] For a detailed discussion of abortion and pill politics in Japan see Tiana Norgren (2001) Abortion before Birth Control.

Seasonale

Starting in 2003, women have also been able to use a three-month version of the Pill.[10] Similar to the effect of using a constant-dosage formulation and skipping the placebo weeks for three months, Seasonale gives the benefit of less frequent periods, at the potential drawback of breakthrough bleeding. Seasonique is another version in which the placebo week every three months is replaced with a week of low-dose estrogen.

Use

Oral contraceptives for women consist of a pill taken daily which contains doses of synthetic hormones (always a progestin and most often also an estrogen).

Combined oral contraceptive pills (which contain both a progestin and an estrogen) must be ingested within 12 hours of the same time each day and progesterone only pills (POPs) within 3 hours. Most brands of combined pills are packaged with 21 days of active (hormone-containing) pills followed by either 7 days of placebo pills, or instructions to not take pills for seven days. A woman on the pill will have a withdrawal bleed, or period, sometime during the placebo week. POPs are taken continuously; most women experience somewhat irregular bleeding while taking them.

If a woman just starting the pill begins taking them on the first day of her menstrual cycle (first day of red bleeding), she will have pregnancy protection from the very first pill. If a woman begins taking the pill at another time in her menstrual cycle, she must use a different form of contraception for seven days.

Mechanism of action

Several different types of 'the Pill' exist. Generally, all oral contraceptives have different synthetic estrogens and progestins, chemical analogues of the natural hormones, estradiol (an estrogen) and progesterone (a progestagen). An exception is the progestin only pill, which lacks estrogen and thus generally has fewer side effects than the combined pill.

The combined Pill primarily prevents pregnancy by preventing ovulation. It also has the side effect of thickening the cervical mucus, which can prevent or slow sperm entry into the uterus. In addition, the Pill thins the endometrium (the lining of the uterus).

Contraception vs Abortion debate

There are physicians and other medical professionals who point to this thinning of the endometrium as evidence that the Pill is an abortifacient.[11] This claim is based on experiences with in vitro fertilization which demonstrated that thinner uterine linings correlated with increased difficulty in getting the test-tube-fertilized blastocyst to implant. However, other physicians (including some pro-life physicians) are unconvinced that this truly does decrease the likelihood that an embryo will implant itself in the uterine lining.

In women who do not take The Pill, the uterine lining is usually unreceptive to implantation prior to ovulation. The purpose of the hormones released by the corpus luteum is to cause the endometrium to thicken and become receptive to implantation (which occurs between six and twelve days after ovulation if the ovum is fertilized). Thus, simple observations that the uterine lining is too thin to support implantation during a cycle where no ovulation has occurred is insufficient to support the claim that there is a reduced likelihood of implantation in ovulatory Pill cycles. Currently, no research has been conducted on the behavior of the endometrium in ovulatory Pill cycles.[12]

The theory that the pill has postfertilization effects is also based on some studies that found the ratio of extrauterine to intrauterine ratio of pregnancies increases by 70–1390% in women using the pill[13][14][15] although not all research reaches the same conclusions.[16] The asserted increased proportion of extrauterine pregnancies is most likely explained by interference of the pill with the normal process of implantation.

There is some controversy over the beginning of pregnancy. The medical consensus is that pregnancy begins with implantation, not fertilization. However some medical sources still define pregnancy as beginning with fertilization. Therefore, if oral contraceptives do interfere with implantation, the determination of whether oral contraceptives are abortifacients depends largely on a person's individual definition of pregnancy.

Effectiveness

The Pearl Index is often used to compare the effectiveness of various methods of contraception.[17] It is expressed as the "number of unintended pregnancies in 100 normally fertile women over the period of one year". Each method of birth control has two Pearl index numbers:

- method effectiveness: is the Pearl index number for use under perfect conditions. The method effectiveness Pearl index for the Pill has been measured as low as 0.3 and as high as 1.25, which means that under ideal conditions, anywhere from 0.3 to 1.25 out of 100 users will become pregnant during one year of perfect use (Pearl index = 0.3 to 1.25).

- user effectiveness or typical effectiveness: is the Pearl index number for use that is not consistent or always correct. The user effectiveness measured by the Pearl index for the Pill has been measured as low as 2.15 and as high as 8.0, which means that anywhere from 2.15 to 8.0 out of 100 women will become pregnant during the first year of typical use (Pearl index = 2.15 to 8.0).[18][19]

Many women occasionally forget to take the Pill daily, impairing its effectiveness. Correct use of the pill usually implies taking it every day at the same hour for 21 days, followed by a pause of seven days.

Use of other medications can prevent the Pill from working, due to interactions with the metabolism of the hormonal constituents. Diarrhea can also stop the Pill from working, because it causes the hormones to not be properly absorbed by the bowels.

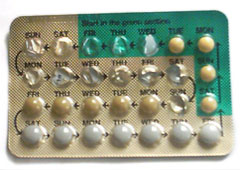

Packaging

The Pill usually comes in two different packet sizes, with days marked off for a 28 day cycle. For the 21-pill packet, a pill is consumed daily for three weeks, followed by a week of no pills. For the 28-pill packet, 21 pills are taken, followed by week of placebo or sugar pills.

The purpose of the placebo pills is that the user, out of habit, can take a pill on every day of her menstrual cycle, instead of calculating the date she should start the next dose. Failure to take placebos has no effect on the effectiveness of the pill provided the regular schedule is followed. If the pill formulation is monophasic, it is possible to skip menstruation and still remain protected against conception by skipping the placebo pills and starting directly with the next packet. Attempting this with bi- or tri-phasic pill formulations carries an increased risk of breakthrough bleeding and may be undesirable. It will not, however, increase the risk of getting pregnant. The presence of placebo pills is thought to be comforting, as menstruation is a physical confirmation of not being pregnant. Breakthrough bleeding also becomes a more common side effect as a woman attempts to go longer periods of time between menstrual periods. The pills may contain an iron supplement, as iron requirements increase during menstruation.

Drug interactions

Some drugs reduce the effect of the Pill and can cause breakthrough bleeding, or increased chance of pregnancy. These include enzyme inducing drugs such as rifampicin antibiotic, barbiturates, phenytoin and carbamazepine. In addition cautions are given about broad spectrum antibiotics, such as ampicillin and doxycycline, which may cause problems "by impairing the bacterial flora responsible for recycling ethinyloestradiol from the large bowel" (BNF 2003).[20]

The traditional medicinal herb St John's Wort has also been implicated due to its upregulation of the P450 system in the liver.

Side-effects

When starting to take the Pill, the majority (about 60%) of women report no side effects at all, and the vast majority of those who do, have only minor effects.[21] [22] [23] Some women report slight weight gain, although most studies show that the incidences of this is about 50% and as many women experience slight weight loss. Some women also notice changes in the intensity of sexual desire, vaginal discharge and menstrual flow.

Other possible side effects are: breakthrough bleeding, unusual build-up of the uterine lining, nausea, headaches, depression, vaginitis, urinary tract infection, changes in the breasts, changes in blood pressure, skin problems, skin improvements, and gum inflammation. The insert included with each pill packet usually has a more extensive list of recognized side effects.

There is contradictory research into the risk of breast cancer.[24] There "is a small increase in the risk of having breast cancer diagnosed in current users of combined oral contraceptives and in women who had stopped use in past 10 years but there is no evidence of an increase in the risk more than 10 years after stopping use" and the nature of the identified cancers being less advanced clinically suggested a bias of screening in oral contraceptives users.[25]

Effects on sexuality

Some say the Pill may have a positive effect on a woman's sexuality. Because neither the woman (who uses the Pill) nor her partner need take any special action before or during intercourse, it makes birth control "invisible" and sex spontaneous, more natural, or both. When combined with the Pill’s high degree of effectiveness, this may enable the couple, and especially the woman, to relax more easily during sex. Masters and Johnson reported more than one woman who experienced her first orgasm during intercourse shortly after going on the Pill.

However, some also say the Pill can also have a negative effect on a woman's sexuality. One doctor (Dr. John Bancroft, a senior research fellow at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University) estimates that one in four women on the pill experience some negative sexual effect. These effects may include a decreased frequency of sexual thoughts, increased difficulty in becoming aroused, or decreased lubrication, which can make sex painful. Recent research co-authored by Dr. Irwin Goldstein (a urologist in Boston) suggests such effects may continue for up to four months after a woman stops taking the Pill.[26]

Cautions and contraindications

Oral contraceptives may influence coagulation, subtly increasing the risk of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, stroke and myocardial infarction (heart attack). However, estrogen contraceptives are usually only contraindicated in women with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, in women who have a familial tendency to form blood clots (such as familial factor V Leiden), women with severe obesity and/or hypercholesterolaemia (high cholesterol level) and most notably in smokers over 35.

Studies of higher-dose, estrogen-based pills have been linked to an increased risk of breast cancer, though no studies have been done on the lower-dose pills more popular today. In rare cases, high estrogen Pills may trigger benign intracranial hypertension.

In Our Sexuality, Crooks and Baur state a commonly held medical opinion about risks associated with Pill use: "In general, the health risks of oral contraceptives are far lower than those from pregnancy and birth."[27] Although widely accepted,[28] at least one organization disputes that conclusion,[29] and others have argued that comparing a contraceptive method to no method (pregnancy) is not relevant - instead, the comparison of safety should be among available methods of contraception.[30]

Non-Contraceptive Uses

The hormones in "the Pill" can be used to treat some medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, adenomyosis, anemia related to menstruation, and painful menstruation (dysmenorrhea). In addition, oral contraceptives are often prescribed as medication for mild or moderate acne.[31] The pill can also induce bleeding on a regular schedule for women bothered by irregular menstrual cycles and certain disorders where there is dysfunctional uterine bleeding.

Combined oral contraceptive use reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 40% and the risk of endometrial cancer by 50% compared to never users. The risk reduction increases with duration of use, with an 80% reduction in risk for both ovarian and endometrial cancer with use for more than 10 years. The risk reduction for both ovarian and endometrial cancer persists for at least 20 years.[32]

Although the FDA does not officially condone the use of the Pill as a minor breast enhancer, many women have gone on the pill in order to increase their breast size. This results from the low doses of estrogen present along with the progestin. Results vary widely.

Social and cultural impact

Introduced at the beginning of the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, the Pill had a big social impact. In the first place, it was far more effective than any previous method of birth control, giving women unprecedented control over their fertility. Its use was separate from intercourse, requiring no special preparations at the time of sexual activity that might interfere with spontaneity or sensation. This combination of factors served to make the Pill immensely popular within a few years of its introduction.[33][34]

Because the Pill was so effective, and soon so widespread, it also heightened the debate about the moral and health consequences of pre-marital sex and promiscuity. Never before had sexual activity been so divorced from reproduction. For a couple using the Pill, intercourse became purely an expression of love, or a means of physical pleasure, or both; but it was no longer a means of reproduction. While this was true of previous contraceptives, their relatively high failure rates and their less widespread use failed to emphasize this distinction as clearly as did the Pill. The spread of oral contraceptive use thus led many religious figures and institutions to debate the proper role of sexuality and its relationship to procreation. The Catholic Church in particular, after studying the phenomenon of oral contraceptives, re-emphasized traditional Catholic teaching on birth control in the 1968 papal encyclical Humanae Vitae. The encyclical, which reiterated the traditional Catholic teaching that artificial contraception distorted the nature and purpose of sex, was greeted with open dissent by many Catholics, which contributed to the rise of a culture of dissent in following years on other Catholic teachings.[35]

A backlash against oral contraceptives occurred in the early and mid-1970s, when reports and speculations appeared that linked the use of the Pill to breast cancer. Until then, many women in the feminist movement had hailed the Pill as an "equalizer" that had given them the same sexual freedom as men had traditionally enjoyed. This new development, however, caused many of them to denounce oral contraceptives as a male invention designed to facilitate male sexual freedom with women at the cost of health risk to women.[36] At the same time, society was beginning to take note of the impact of the Pill on traditional gender roles. Women now did not have to choose between a relationship and a career; singer Loretta Lynn commented on this in 1975 with a song entitled "The Pill," which told the story of a married woman's use of the drug to liberate herself from her traditional role as wife and mother.

Environmental impact

Ethinylestradiol, the synthetic estrogen used in combined hormonal contraceptives, is excreted in the urine of women users. Sewage treatment processes do not remove these chemicals, and they are discharged into the water system. This form of pollution has been proven to have reproductive and other effects on aquatic organisms, including fish, frogs, and zooplankton. Feminization of male fish, even to the point of producing eggs, is one common effect. Both male and female fish experience delays in reproductive development, and changes are seen in their kidneys and livers.[37]

Footnotes

- ^ Department of Health, National Statistics. NHS Maternity Statistics, England: 2002–03.

- ^ a b Aiko Hayashi. "Japanese Women Shun The Pill", CBS News, August 20, 2004. Retrieved on 2006-06-12.

- ^ A Pill for the People WGBH Nova biographical profile of chemist Russell Marker, original broadcast date March 9, 1977, and the book Vaughan, Paul (1970). The Pill on Trial. New York: Coward-McCann.

- ^ Birch, A.J. (1974). "Chance and Design : An Historical Perspective of the Chemistry of Oral Contraceptives". Journal and Proceedings of The Royal Society of New South Wales 107 Parts 3 and 4: 100-113.

- ^ 33 Fed. Reg. 9001 (1970) (codified at 21 C.F.R. §310.510)

- ^ Dourlen Rollier, AV (1972). "Contraception: yes, but...". Fertilite, orthogenie 4 (4). PMID 12306278.

- ^ The Aids Generation: the pill takes priority?. Science Actualities (2000). Retrieved on 2006-09-07.

- ^ Stanford University News Service (96-14-02). Djerassi on birth control in Japan - abortion 'yes,' pill 'no'. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-08-23.

- ^ Japanese Women Shun The Pill. HealthWatch. CBS News (August 20, 2004). Retrieved on 2006-08-23.

- ^ FDA Approves Seasonale Oral Contraceptivel (September 25, 2003). Retrieved on 2006-11-09.

- ^

Colliton, William F. (1999).

Birth Control Pill: Abortifacient and Contraceptive.

Retrieved on

2006-08-30.

Wilks, John (October 1998). The Pill – How it works and fails. Pharmacists For Life International. Retrieved on 2006-08-30. - ^ Hormone Contraceptives Controversies and Clarifications. American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (April 1999). Retrieved on 2006-06-12.

- ^ (1985) "A multinational case-control study of ectopic pregnancy. The World Health Organization's Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction: Task Force on Intrauterine Devices for Fertility Regulation.". Clin Reprod Fertil 3 (2): 131-43. PMID 4052920.

- ^ Job-Spira N, Fernandez H, Coste J, Papiernik E, Spira A (1990). "Risk of chlamydial PID and oral contraceptives.". JAMA 264 (16): 2072-4. PMID 2278576.

- ^ Coste J, Job-Spira N, Fernandez H, Papiernik E, Spira A (1991). "Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a case-control study in France, with special focus on infectious factors.". Am J Epidemiol 133 (9): 839-49. PMID 2028974.

- ^ Mol B, Ankum W, Bossuyt P, Van der Veen F (1995). "Contraception and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis.". Contraception 52 (6): 337-41. PMID 8749596.

- ^ Pearl R. (1933). "Factors in human fertility and their statistical evaluation". Lancet 2: 607-611.

- ^ Audet MC, Moreau M, Koltun WD, Waldbaum AS, Shangold G, Fisher AC, Creasy GW (2001). "Evaluation of contraceptive efficacy and cycle control of a transdermal contraceptive patch vs an oral contraceptive: a randomized controlled trial" (Slides of comparative efficacy]). JAMA 285 (18): 2347-54. PMID 11343482.

- ^ Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive Use. Facts in Brief. Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved on 2005-05-10. - see table First-Year Contraceptive Failure Rates

- ^

The effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on

Combined contraceptive pills is not found on

systematic interaction metanalysis (Archer, 2002),

although "individual patients do show large

decreases in the plasma concentrations of ethinyl

estradiol when they take certain other antibiotics"

(Dickinson, 2001). "...experts on this topic still

recommend informing oral contraceptive users of the

potential for a rare interaction" (DeRossi, 2002)

and this remains current (2006) UK

Family Planning Association advice.

- Archer J, Archer D (2002). "Oral contraceptive efficacy and antibiotic interaction: a myth debunked.". J Am Acad Dermatol 46 (6): 917-23. PMID 12063491.

- Dickinson B, Altman R, Nielsen N, Sterling M (2001). "Drug interactions between oral contraceptives and antibiotics.". Obstet Gynecol 98 (5 Pt 1): 853-60. PMID 11704183.

- DeRossi S, Hersh E (2002). "Antibiotics and oral contraceptives.". Dent Clin North Am 46 (4): 653-64. PMID 12436822.

- ^ What are the Side Effects of The Pill?. About, Inc. Retrieved on 2006-10-17.

- ^ Birth Control Pill. The Nemours Foundation. Retrieved on 2006-10-17.

- ^ The Pill: Side Effects & Current Issues. University of New Mexico Student Health Center. Retrieved on 2006-10-17.

- ^ The combined pill - Are there any risks?. Family Planning Association (UK). Retrieved on 2006-10-17.

- ^ Plu-Bureau G, Lę M (1997). "[Oral contraception and the risk of breast cancer]". Contracept Fertil Sex 25 (4): 301-5. PMID 9229520. - meta-analysis of original data from 54 studies representing about 90% of the published epidemiological studies, prior to introduction of third generation pills.

- ^ Duenwald, Mary. "When the Pill Arouses That Urge for Abstinence", The Consumer, The New York Times, January 10, 2006. Retrieved on 2006-09-07. (url requires free registration)

- ^ Crooks, Robert L. and Karla Baur (2005). Our Sexuality. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 0534651763.

- ^

Questions and Answers About the Pill: Current Pill

Use. American Experience. PBS (2002).

Retrieved on

2006-10-07.

Lie, Desiree (2000). Contraception Update for the Primary Care Physician. Medscape. WebMD. Retrieved on 2006-10-07.

Birth Control Pill ("The Pill"). Advocates For Youth (2005). Retrieved on 2006-10-07. - ^ Weckenbrock, Paul (1994). Is the Pill safer than pregnancy?. The Pill: How Does it work? Is it Safe?. The Couple to Couple League. Retrieved on 2006-10-07.

- ^ Holck, Susan. Contraceptive Safety. Special Challenges in Third World Women's Health. 1989 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association. Retrieved on 2006-10-07.

- ^ Huber J, Walch K (2006). "Treating acne with oral contraceptives: use of lower doses.". Contraception 73 (1): 23-9. PMID 16371290.

- ^ Speroff, Leon; Darney, Philip D. (2005). “Oral Contraception”, A Clinical Guide to Contraception, 4th ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp. 21-138. ISBN 0-78-176488-2.

- ^ Asbell, Bernard (1995). The Pill: A Biography of the Drug That Changed the World. Random House.

- ^ Watkins, Elizabeth Siegel (2001). On the Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, 1950-1970. Johns Hopkins.

- ^ George Weigel (2002). The Courage to Be Catholic: Crisis, Reform, and the Renewal of the Church. Basic Books.

- ^ Andrea Dworkin (1976). Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics. Harper & Row.

- ^ Karen Kidd (October 2004). "Effects of a Synthetic Estrogen on Aquatic Populations: a Whole Ecosystem Study". Freshwater Institute, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Retrieved on 2006-07-23.

External links

- The Birth Control Pill CBC Digital Archives

- The Pill. American Experience. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved on 2006-08-14.

- A new pill that completely suppresses menstruation

216.73.216.133

216.73.216.133 User Stats:

User Stats:

Today: 0

Today: 0 Yesterday: 0

Yesterday: 0 This Month: 0

This Month: 0 This Year: 0

This Year: 0 Total Users: 117

Total Users: 117 New Members:

New Members:

216.73.xxx.xxx

216.73.xxx.xxx

Server Time:

Server Time: